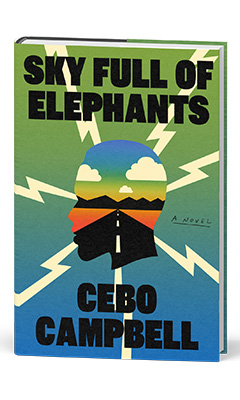

Sky Full of Elephants

by Cebo Campbell

Brooklyn-based writer and creative director Cebo Campbell stuns with his kaleidoscopic speculative debut, Sky Full of Elephants, about a world reforming in the aftermath of whiteness. One-part philosophical thought experiment, and one-part thrilling road-trip odyssey, Campbell's novel entertains as it enlightens.

One beautiful summer day, every white person in America walks straight into the nearest body of water and drowns themselves. This is the unexplained, cataclysmic event that has forever changed the world of Campbell's novel. A year later, Charlie Brunton may be living the benefits of this event, but he's also still grappling with its implications for his past, his future, and his identity. Imprisoned for years for a crime he didn't commit, Charlie now finds himself a professor at Howard University, where he nominally instructs about electric and solar power systems, but often feels like he's teaching much more than that, especially in a world that is still figuring out how to run itself in the absence of its most domineering population.

When Charlie gets a phone call from his estranged daughter, Sidney, asking for his help, he can't bring himself to say no. Sidney, who has been raised by her white mother and stepfather, finds herself abandoned in her family's home in Wisconsin, haunted by the deaths she witnessed. She is determined to go to Alabama, where she believes some of her "real" family remains, so Sidney and Charlie set out through the crumbling and spectacular landscapes, haunted and thriving, of a post-racial country, becoming first-hand witnesses to a world reborn.

Campbell succeeds at crafting, lucidly and beautifully, the small details of this new world. While seemingly minute, these eye-opening moments speak volumes not only about the novel's particular brand of utopianism, but also about the world as it is now. When Charlie and Sidney visit the airport, for example, they find that "the airport terminal vibed more like a night market, buzzing with the chatter of people, the clatter of forks and spoons on plates, grills hissing, vendors clamoring, horns barking music through the clutter of color, noise, and confusion. So many smells, spicy, sweet, and charred." The "buzzing" presence of vibrant life here is as breathtaking to readers as it is to Charlie and Sidney. But just as readers experience the night market, they also experience the uncanny relief of absences: no airport security, drug-sniffing dogs, sterile VIP lounges, or even many planes. This scene, like many others in Campbell's novel, makes magic out of sound: what can be heard and what can't, and the ever-present quality of low-frequency registers, or those sounds of absence that echo even in the deafening roar of the present.

Like the airport night market, what Charlie and Sidney find on their journey--both across the landscapes of America and within themselves--is never quite expected, yet Campbell's lyrical prose and convincing portraits of complex social structures persuade readers, again and again, of their reality. What awaits them in Alabama, for example, might feel surprising at first, but are revealed to be logical progressions more than pure imagining. Yet the way this world operates makes places like this conjured Mobile feel no less miraculous. Charlie proves to be an ideal guide through this both reasonable and extraordinary world. As a person who "understand[s] systems... any kind, really," Charlie always seeks to navigate the entanglements among one's sense of self; systemic structures of racism, sexism, and capitalism; and the logistical workings of a reconfigured world.

Yet despite Charlie's adeptness with "systems" (which he specifies as "especially electrical," but what the novel means more broadly) and his ability to fix things, his arc--like any arc that seeks to trace such complex and heady topics--is not so straightforward. The novel's ending provides no easy solutions or answers, just more journeys of self-discovery to be had. Instead of providing neat conclusions, Campbell is more invested in exploring messy middles. Again and again Campbell's characters must face what the narrative characterizes as "knots": knots of "tension" within themselves "that never seemed to unravel"; the "unmeasured knot of time" that knits together the past and the present; "a knot of traumas" that Charlie believes is all he has "to offer his only daughter"; or even just "a knot of wires" that Charlie must ultimately grapple with to fix the most important machine he'll ever work on. As one character ultimately diagnoses him, "You ain't a man. You a knot. A conflict.... Without understanding the shape of yours, you'll never be a full human being." If Campbell’s novel is a book full of knots, it's one that honors what it means to sit down with the messiness of what both society and individual human beings often don’t want to face. --Alice Martin