The Divorce Papers

by Susan Rieger

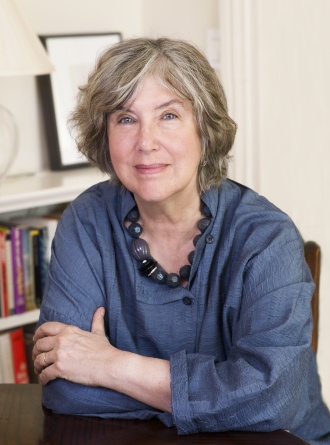

Chances are you've never read a novel quite like The Divorce Papers. Former university professor and law teacher Susan Rieger gives the epistolary form a fun, unique twist, interspersing personal letters and e-mails with interoffice memos, briefs, transcripts, worksheets and other legal documents to deliver a clever, engaging story along with a crash course in divorce law.

Murder, not divorce, is attorney Sophie Diehl's specialty. Warring spouses aren't her bailiwick, plus she abhors client interaction and couldn't be happier most of hers are behind bars with limited means of contact. So when she winds up helming a high-profile divorce case, she is as surprised as anyone.

Sophie's detour into civil law begins after she pinch-hits for her firm's partners by doing an intake interview with Mia Durkheim, the divorcing daughter of their most important client. Her boss assures her that will be the end of her involvement in the case, but Mia shrewdly sizes up Sophie and asks that she be the one to represent her. In her mind, a criminal lawyer is exactly who she needs to combat the hardball attorney her philandering husband hired.

When Sophie protests that she's ill-equipped legally--and temperamentally--to take on the case, Mia tartly tells her, "This is my first divorce, too." The gamble pays off. Using tactics honed defending hardened criminals, Sophie is a formidable foe, going toe to toe with opposing counsel and even teaching the seasoned divorce lawyers in her firm a thing or two.

If Mia were to commit murder, her spouse of 18 years would top the list of targets. Despite a marriage that went from ardent to average, she believed that she and Daniel would stay together for the sake of their daughter and "live unhappily ever after." Instead Mia is surprised and humiliated when she's served with divorce papers while lunching at her favorite restaurant, Golightly's. After recovering from the shock, she promptly orders a bottle of Pouilly-Fuissé.

Although Sophie reluctantly takes on Mia's case, her unwanted client turns out to be the smartest, funniest, most interesting one she's worked with. Together they dish Daniel--a first-rate doctor and third-rate human being--the comeuppance he deserves. Anchoring the story is the two women's entertaining correspondence, which is peppered with literary references, salty language and musings on topics such as the seven stages of divorce. "I somehow feel uninhibited writing to you. I figure you have to have heard worse," Mia confesses to her lawyer and pen pal.

Much livelier and faster paced than the title implies, The Divorce Papers unfolds with sassy Sophie at its center. On the brink of turning 30, she starts taking stock of her life, personally and professionally, comparing herself to "one of those exasperating Austen heroines, Marianne or Emma, ardent and self-centered. But they turn out all right, so maybe...."

Readers get to know Sophie in and out of the workplace as she deals with office politics, including a spiteful colleague who thinks the young lawyer stole her case, romantic drama that has shades of Portnoy's Complaint and thorny family affairs. Working with Mia unearths old wounds for Sophie and finally compels her to come to terms with her parents' devastating, acrimonious divorce 13 years earlier.

Like Sophie and her siblings once were, Mia's daughter, Jane, is caught in the chaos of her parents' marital meltdown and finds solace reading books (she proudly shares a birth date with Shakespeare). The most poignant part of the story is a psychologist's evaluation of the sad, spunky 10-year-old, who takes charge of an uncertain future with the self-assurance of an adult.

By juxtaposing legal documents with personal correspondence, readers are given an eye-opening look at the inner workings of the divorce process as well as the emotional impact on those involved when a marriage fails. Rieger brilliantly blends the serious and the comic, offsetting the weighty topic of divorce with (sometimes dark) humor--like when Mia declares that for her, post-divorce bliss will be a brand-new, king-size bed and the news that a certain part of her husband's anatomy has fallen off.

A bonus for bibliophiles and movie buffs is the abundant book and film references throughout the novel, from Dickens and David Foster Wallace to Star Trek and All About Eve. One character refers to another's personality as part Hamlet and part King Lear, while another likens his mother to Grace Kelly's parent in To Catch a Thief, down-to-earth and a bourbon drinker. When Sophie's best friend offers to set her up with a blind date, she asks, "Is he more Rochester or Heathcliff?"

When Sophie is first assigned to Mia's case, her boss warns her, "In divorce, there are very few satisfied customers." Not so with this immensely enjoyable debut novel. The verdict: if you like your fiction smart and witty, The Divorce Papers is a winner. --Shannon McKenna Schmidt