|

|

| Chris Colderley, Marjory Wentworth and Kwame Alexander (photo: Joanna Crowell) | |

Kwame Alexander is a poet, educator and author of 21 books including The Crossover, which was awarded the 2015 Newbery Medal. He is the poet laureate of LitWorld, a K-6 literacy organization, and lives in Virginia. Here, Alexander ropes in his co-authors of Out of Wonder: Poems Celebrating Poets (Candlewick, March 14, 2017), Chris Colderley and Marjory Wentworth, to answer some questions for Shelf Awareness. As he says, "I guess you'll have to wonder who said what. Onwards!"

Out of Wonder: Poems Celebrating Poets is a dynamic homage to 20 different poets. Tell us about where the idea for the book came from.

When I visit schools, I read poetry. My poetry. Other people's poetry. I wanted to write a book that celebrated some of those poets that I share with students in my travels. I wanted to introduce them to my favorite writers who've inspired and excited me since I was a kid. I also thought, how cool would it be to facilitate this introduction by mimicking some of these poets.

I came up with this idea in 2014, and in 2015 I had to write it. This was the year, of course, when I won the Newbery. Linda Sue Park gave me some advice: Don't try to write a book this year. And, she was right, it was a wonderfully overwhelming year and to have to write on top of all the other obligations wasn't feasible. Well, I didn't follow that advice. I wrote four books. The way I did it was by collaborating.

How did you choose Chris Colderley and Marjory Wentworth as your fellow poets?

How did you choose Chris Colderley and Marjory Wentworth as your fellow poets?

Chris and I have been friends and colleagues for five years. We even went to Bahia for two weeks for a cultural exchange program and to write poetry. Marj and I have been friends for over 10 years. We went to Tuscany to write poetry together (and to drink wine). They are both amazing teachers, and much better writers than me. And, I absolutely adore their poetry. And, I like them. A lot. It just made sense to ask them to write it with me.

How did you collaborate with them?

That's a trade secret. But, I will say this, I am a great curator of people. I know how to get them to work together, efficiently and effectively, even when one lives in South Carolina (Marjory), and one lives in Canada (Chris). So, I curated, and once we had a draft of the book together, we met for a weekend in Folly Beach, South Carolina, and spent most of our time laughing and eating Charleston cuisine. And, we even wrote a little.

Were there any surprises in the process? Did you ever fight over a poet?

When you participate in a collaborative effort, there are always surprises and differences of opinion. Initially, we each made our own list of 20 poets to decide who should be included. Surprisingly enough, very few poets appeared on all three lists. Several appeared on two lists. Finally, there were a handful that appeared on only one list. Our relationship was such that we could negotiate differences. We respected each others' passion enough to allow each writer to pursue a poet they believed in strongly.

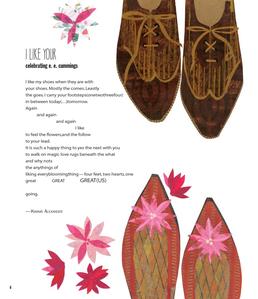

E.E. Cummings was an interesting case. My enthusiasm and inspiration for Cummings's poetry convinced the rest of us that he should be included in the book. I think "Your Shoes" is one of the most whimsical and fun poems in the whole collection.

E.E. Cummings was an interesting case. My enthusiasm and inspiration for Cummings's poetry convinced the rest of us that he should be included in the book. I think "Your Shoes" is one of the most whimsical and fun poems in the whole collection.

The poet who generated the most controversy was Boris Pasternak, the 20th-century Russian aristocrat. We did write a biography and a poem about Pasternak, but it became clear that his work did not bring the inspiration or enthusiasm we wanted in this book.

You wrote: "There is a feeling of connection and communion--with the author and the subject--when we read a poem that articulates our deepest feelings." Tell us more about that.

The readers recognize themselves in the poem. They think, "that poet has felt what I've felt, s/he has been in my shoes." It's a deeply universal human connection we recognize when it's articulated, and it makes us feel less alone. That's why we turn to poetry in a time of crisis, whether personal or social. We turn to language to make sense of the unexplainable.

Did you share any of the poems from this book with the (still living) poets they celebrate?

I had dinner with Nikki Giovanni and Ashley Bryan (one of my poet/artist heroes), and I showed them both the advanced reading copy. I didn't tell Nikki that there was a poem about her in the book, and when she saw it, the smile on her face could have lit up the night sky. She's my shining star and, if she didn't know that, she knows it now.

It must have been fun adopting the styles and rhythms of the poets in your book. My favorite line in your E.E. Cummings ode is, "It is such a happy thing to yes the next with you." Are there any poets who have powerfully influenced your own style?

It must have been fun adopting the styles and rhythms of the poets in your book. My favorite line in your E.E. Cummings ode is, "It is such a happy thing to yes the next with you." Are there any poets who have powerfully influenced your own style?

Now, that is such a beautiful question because it's the perfect set-up for me to say to all your readers: "Go out and buy or check out Out of Wonder, Kwame Alexander's new picture book about all the poets who have powerfully influenced his own style!"

Do you advise young poets to mimic the styles of poets they like?

Absolutely. I began by imitating Langston Hughes and Nikki Giovanni. T.S. Eliot said, "Immature poets imitate, mature poets steal." The way we learn how to write is by reading other writers. I say take that a step further and mimic their style, their voice, as it's a great exercise in craft. It's practice. Do it enough, and you just may find your own voice, your own style. I did. WOOHOO!

There's a lot of movement and music in the poems of Out of Wonder.

Kids love to move. The more energy within the poem, the better for the kids. It's all about harnessing all that energy within the lines of the poem. Langston was inspired by jazz and it showed in his poems. Nikki by gospel. I think the best poets hear the rhythm of life in their hearts and try to make its woes and wonders dance on the page.

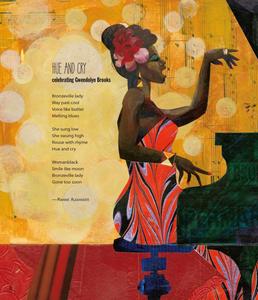

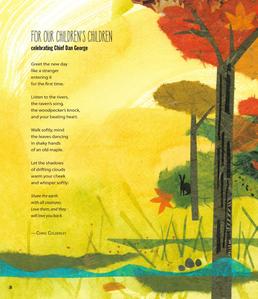

Did you collaborate with Ekua Holmes on pairing the poems with the illustrations?

Did you collaborate with Ekua Holmes on pairing the poems with the illustrations?

I sent positive vibes to her. I took her out to dinner. We laughed. I heard her Coretta Scott King Award speech. I left her alone. To work her magic. I smiled.

In your preface you say you fell out of love with reading when you were around 10 years old.

It's true. I found my way back to books through girls. Love. Writing love poems for girls. To get dates. Reading Neruda and Sonia Sanchez. I once wrote a girl a love poem every day for a year. And, she married me. So, yeah, I was reunited with a love of words by, uh, love.

I know you give poetry workshops all the time, all around the country. What do you tell the kids to help them find their voices?

Good question. First, I play different types of music to identify voice. Jazz doesn't sound like country, for example. They get that. Sometimes I have them create a box of words--words they use and are familiar with. They write them out and cut them up and put them in their own box. This gives them their own vocabulary for them to use to "build" their poems. No two boxes of words are the same. If they speak Spanish or Gullah or Tagalog for example, I encourage them to draw from that language as well. Also, I read a lot of poetry to them. I mean, a lot. And they love it, and then they wanna do it themselves.

What have you learned from the kids while visiting all these classrooms?

Wow. I am sure I learn more from them than they learn from me! Their innate creativity always astonishes me. So often they write something that touches my heart and demonstrates their goodness. The toughest kid often turns out to be the biggest softie. I mean that in the best possible way. Their sense of wonder about the world around them is the gift they always bring to me. --Emilie Coulter