You've seen, heard or posed the question. The New York Times Book Review's "By the Book" series asks it this way: "You're organizing a literary dinner party. Which three writers, dead or alive, do you invite?"

I once considered the question in an essay, imagining a dinner in 19th century Concord with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Bronson Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Margaret Fuller. But the fantasy came with a reality check: "Given my working-class heritage, though, I'd probably have been serving them soup."

|

|

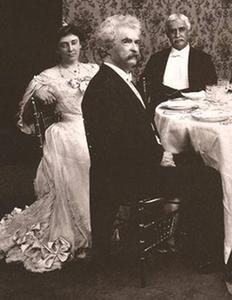

| Mark Twain's 70th birthday dinner at Delmonico's in New York City | |

This week, the birthday of another notable Concord resident sparked renewed consideration of literary dinner parties, and the stakes were raised dramatically when I discovered other potential guests lurking nearby.

Louisa May Alcott turned 184 and C.S. Lewis 118 on Tuesday, just a day before Samuel (Mark Twain) Clemens hit 181 years old and Jonathan Swift a spry 349.

They all still look good for their ages--books in print, myriad biographies and scholarly works available, and perennial international media coverage of their birthdays. If you're a dead author, who could ask for anything more?

I was propelled down this rabbit hole of dead author birthday awareness when Main Street Books, Mansfield, Ohio, shared a Facebook post from Books with a Past, Glenwood, Md., featuring a necklace and Alcott's words: "She is too fond of books and it has turned her brain." I knew it was time to send out the invitations and consider topics for discussion.

|

|||

|

|||

In a Guardian piece headlined "Louisa May Alcott: a practical utopian from a divided U.S.," Rafia Zakaria observed that while she "may have balked at or been baffled by many of the conventions of today's America--being the subject of a Google Doodle might have surprised her--the divisions of its politics dominated once again by race and inequality would not have surprised her. The postbellum U.S. into which Little Women was released had been racked by its disagreements over slavery, the southern half couching its support for slavery in the language of economic survival. This year's presidential election, coming more than 150 years after the end of the civil war, pivoted once again on the maintenance of white privilege, cast now in the coded vocabulary of lost manufacturing jobs."

And on Maria Popova's Brain Pickings blog, I found this conversation starter from Lewis:

Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realize the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors. We realize it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others.

Then I went to my own bookshelves for Mark Twain's RSVP and found it in the first volume of his autobiography:

I believe that the trade of the critic, in literature, music, and the drama, is the most degraded of all trades, and that it has no real value--certainly no large value.... However, let it go. It is the will of God that we must have critics, and missionaries, and Congressmen, and humorists, and we must bear the burden. Meantime, I seem to have been drifting into criticism myself. But that is nothing. At the worst, criticism is nothing more than a crime, and I am not unused to that.

The frosting on this conversational birthday cake was re-reading Jonathan Swift's wicked, brutally satiric essay "A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland from Being a Burden to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public."

Is there room for one more guest?

Another November 29 birthday celebrant, the late Madeleine L'Engle (a mere 98 extended years old), said in a 1983 lecture at the Library of Congress:

Another November 29 birthday celebrant, the late Madeleine L'Engle (a mere 98 extended years old), said in a 1983 lecture at the Library of Congress:

We all practice some form of censorship. I practiced it simply by the books I had in the house when my children were little. If I am given a budget of $500 I will be practicing a form of censorship by the books I choose to buy with that limited amount of money, and the books I choose not to buy. But nobody said we were not allowed to have points of view. The exercise of personal taste is not the same thing as imposing personal opinion.

What a conversation this is going to be. Is there even room for me, sitting silently and in awe, at the table? Well, I did fall down a rabbit hole, after all, so: "The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it: 'No room! No room!' they cried out when they saw Alice coming. 'There's PLENTY of room!' said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table."

Let's get this literary birthday dinner party started.