|

|

| photo: Elena Seibert | |

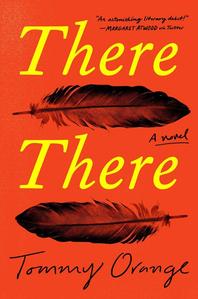

Tommy Orange is a recent graduate of the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. He was a 2014 MacDowell Fellow and a 2016 Writing by Writers Fellow. He is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. His debut novel, There There (Knopf), is reviewed below.

When did you start writing and decide that this was your calling?

I came to it pretty late. I was kind of doing it unconsciously in the margins of textbooks and on the backs of notes. I have a distinct memory of writing weird little lines everywhere. I did not consider myself a writer, was not headed in that direction. I graduated from college with a bachelor's of science in the sound arts. I was a musician, but did nothing with my degree. I got a job at a used bookstore, and while I was working there, fell in love with literature; from there, I decided I wanted to write. I spent the rest of the time playing catch-up with everyone who knew for a long time they wanted to write.

How did getting your MFA at the Institute of American Indian Arts--which offers the first indigenous-centered MFA program in the U.S.--change your writing?

I was three or four years into the middle of writing a novel when I started the program. I definitely picked up a lot of tools--there's an amazing faculty there. Also, it was really important to become a part of a writing community. There was a lot of support and energy that added to everything. I felt like I wasn't writing in a void. That helped in a lot of intangible ways.

The prologue and interlude in There There are so powerful. They sound like a universal song, or lament, that is always being sung in the background to the novel.

I wanted a prologue, and originally there wasn't an interlude, but my editor wanted to break it up--there were 14 pages of it. The way it worked out was perfect. It did always feel like I was trying to write something in a collective voice--the royal "we." As Native people, sometimes we feel we have to explain ourselves or set the record straight because our stories have been told wrong or not told for so long. I really wanted to reach back and update, and to explain what urban Indians are. There are Native families who have been living in cities since the 1950s, and 70% of Native people live in cities now, so it was a way of catching people up on what it means to be urban Indian, the relationship with a city that's its own thing, and I felt I needed to put that in at the beginning to contextualize.

In the U.S. as a whole, we like to think of Indians historically and romantically; if we think of urban Natives, we think of homelessness and alcoholism. You write, "We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere." You are pushing against stereotypes.

In the U.S. as a whole, we like to think of Indians historically and romantically; if we think of urban Natives, we think of homelessness and alcoholism. You write, "We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere." You are pushing against stereotypes.Yes, that's what I was doing with the prologue. We've been facing these stereotypes and these old tropes for so long. If you feel some rage in there, that's because it's really there. We are dying to be seen just as human and equal. And present-tense people.

Author Terese Mailhot said that she prefers to be called Indian because it's a "stark word, one embedded in the bureaucracy of North America." In There There, you use multiple words--Indian, Native, Native American, Urban Native, Indigenous.

Most Native people I know just use "Native" as shorthand. They don't say Native American or American Indian. Some other communities say Indigenous. I'm okay with Indians calling each other Indian, but it's uncomfortable for me to hear non-Natives saying "Indian." There are certain times when I will slip into saying "Indian"--it depends on the context.

I like what Terese said, and I like that we struggle with this, and that it's uncomfortable for us to even pronounce a people, because of how uncomfortable the very history is. We have a lot of reckoning to do with our history.

You said, "One of the reasons I wrote a polyphonic novel is that I come from a voiceless community." Was it difficult writing in different points of view?

It was difficult for a lot of reasons. There weren't too many other works to look at, for one. There are no other urban Indian novels that I know of, at least, there weren't when I was writing mine. It's super complicated to have everybody's stories get woven together into one whole story, but the powwow--being the place they all converged--gave me a guiding light.

What is the importance of powwows?

It means different things to different people, but I like it because it's both traditional and contemporary, and it's a place where we can dance, where there are competition and prizes, where we can work on and sell our jewelry. We get to see each other--it's intertribal--and it's a connection to our culture and heritage. You hear loud singing, booming drums--it's unapologetic and proud.

In the Thomas Frank chapter--before he was born, he "swam to the beat" of an arrhythmic heart--the percussion in his very being resonated with the sound of powwows.

People have commented on that chapter as being rhythmic, and I honestly did not intend to do it that way. That chapter is semi-autobiographical, and it came flying out of me in a very short time period. There wasn't much thinking as far as doing conceptual things with it. It really just happened fast.

In the first chapter, the test pattern Indian on Tony's TV sets up the importance of reflections for each of your characters--they look at themselves in mirrors, screens, metal surfaces. Are they searching for their true selves?

It's meant to function as a lot of different things. One is reflection, and looking for what is Indian about themselves--they are struggling with identity. The test pattern Indian reflects how we are depicted on screen; screens are ever-present in our lives now.

Who are your literary heroes? Who do you like to read?

Off the top of my head: Borges, Kafka, Clarice Lispector, Sylvia Plath, John Kennedy Toole, Roberto Bolaño, Marlon James, Alejandra Pizarnik, Ocean Vuong, Louise Erdrich. --Marilyn Dahl