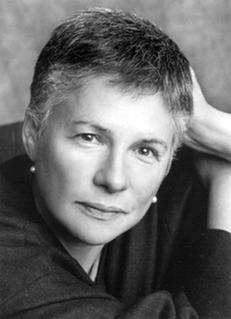

Katharine Weber is a novelist, and an acclaimed one at that. From her first book, Objects in the Mirror Are Closer than They Appear (just reissued by Broadway Books) to The Music Room, The Little Women, Triangle and True Confections, she has created an impressive body of fiction.

Katharine Weber is a novelist, and an acclaimed one at that. From her first book, Objects in the Mirror Are Closer than They Appear (just reissued by Broadway Books) to The Music Room, The Little Women, Triangle and True Confections, she has created an impressive body of fiction.

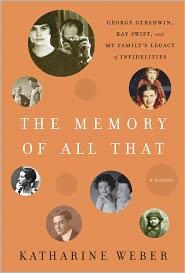

But now Weber has written a memoir, The Memory of All That: George Gershwin, Kay Swift, and My Family's Legacy of Infidelities (Crown, July 19, 2011). Many people (especially Gershwin devotees and biographers) already know that Weber's maternal grandmother, songwriter Katharine Swift Warburg, had a decade-long affair with the composer George Gershwin while she was married to Jimmy Warburg, scion of the banking dynasty that was very powerful in early- and mid-20th-century America.

However, there's more to the book than George and Kay's love (which ended only when Gershwin died from a brain tumor). What does "My Family's Legacy of Infidelities" mean?

Weber is referring to her father's many extramarital affairs and shady business dealings (which included his having a huge FBI file that even noted Weber's birth)--as well as his faithlessness as a father. One of the most poignant scenes in the book is an early one in which young Katharine and her father head out to buy the family Christmas tree. Sidney is intent on getting the best deal possible, even if it means walking away from the tree seller, but he never tells his small daughter that he definitely plans to bring home a tree. The reader is immersed in a child's despair and confusion.

"One of the things I wanted to do was stay in the child's experience and not do that grownuppy, overvoicey thing that can rob moments like that of authenticity," Weber said. "But I'm so not a writer who captions things with 'This is what I'm telling you, here.' I don't do that; I don't write for everybody. "

Weber may not write for everybody, but one of the strengths of her new book is that she wants to write about everyone. "To me it's not just the pebble dropping in the stream that's interesting, it's the circles and circles and circles that get wider after it has dropped. I'm a novelist. I can't ever write about just one thing. How could I write about Kay Swift without writing about the Warburgs? How could I write about the Warburgs without writing about Kay's affair with George? If I wrote about that affair, I had to write about how it affected my family--and me."

When asked who was unfaithful to whom, Weber explained, "Well, there were infidelities in every sense. The FBI thought my father was unfaithful to his country. My grandfather was hideously unfaithful to his whole family. My grandmother was unfaithful to her daughters, but incredibly present with me--and faithful, until the day she died, to George Gershwin's memory."

One of the themes readers will find running through The Memory of All That is mirroring, including a remarkable moment of serendipity in which Weber, interviewing the acclaimed novelist Madeline L'Engle, realizes that a woman in a mirror in one of L'Engle's short stories is based on "Ganz," as Weber and her siblings called their grandmother Kay Swift. But the most haunting instance of mirroring is a photograph that George Gershwin took of himself with Andrea, Weber's mother, when Andrea was just 12 years old.

"The photo as Gershwin printed it is tightly cropped, but the full photo, which I have and which the Gershwin Trust doesn't own, shows you more of the room. When you see the full room, you can see that it's clearly night. Why is Gershwin in this room at night, taking a picture of a 12-year-old girl who looks so unhappy? She's not smiling. It's hard to know what's going on." Weber is not planning to deconstruct the photo, any more than she tries to trace the mirroring trope in her book.

"I thought, when I was younger, that I wanted to write about this charmed circle. Wouldn't you have? I mean, I remember at one party my parents held being under the piano, staring at Harold Arlen's shoes. Some of it was pretty great," Weber admitted. "But I didn't want to write about just the charmed bits, and really, there would never be enough information."

However, Weber the novelist realized, finally, that "anything I write is a lot more than information! I want to wear my research very lightly, and I want it to serve the story. I want any reader to feel that she is in sure hands. Just sit back and read--here's what comes next."

When what comes next is difficult or disturbing, Weber believes it should be included because it's necessary, but she never writes about anything just for prurience. "It's confounding to know that some early reviewers are using the word 'dysfunctional' about my family and my memories, because I never use that word. This book is not a complaint. For example, I do write about all sorts of infidelities, sexual and otherwise, but I never write about how dare he or how dare she. It's much more interesting when you go beyond that, and it's also much more emotionally authentic. It's kind of a default cliché to be outraged. "

"It's not a kitchen sink of a book," Weber continued. "There's always more, and I could have gone in any direction and found it. I wanted, finally, to be true to the story I needed to tell."