Fiction writers toil

alone for years before a note from a complete stranger shows

he/she gets what you're trying to do and is crazy in love with it. Can you

recall a moment when that happened for you?

Fiction writers toil

alone for years before a note from a complete stranger shows

he/she gets what you're trying to do and is crazy in love with it. Can you

recall a moment when that happened for you?

I once got a letter from a reader of All About Lulu, describing how recently he'd been driving down Interstate 10, past the dinosaurs of Cabazon, when suddenly all of these vivid recollections of a night he'd spent there long ago came flooding back. He remembered the stars splashed across the sky, and a deep yearning, and an inclement restlessness stirring him from deep within, and a bottle of rum, and a small group of friends, and the buzzing of heat-dazed crickets. He was visited by an old, deep longing, as he sped past Cabazon on the Interstate.

But he couldn't figure out what the hell he'd been doing there in the first place. He didn't live anywhere near Cabazon. As far as he could remember, he'd never even driven past the place. He couldn't remember who broke his heart. He was never much of a rum drinker. None of it made sense, and yet it was so real. Finally, it occurred to him that what he was remembering was a story an old friend had told him about a night he'd spent in Cabazon. But then, that didn't make sense either. Who did he know that would've been out here? And why would he remember a heartbreak that was not his own so vividly? It wasn't until the next day that he figured out that what he'd been remembering was a scene from All About Lulu.

That meant the world to me, because that's my goal, both as a writer and a reader: to forget about myself, and experience something authentic, as though I am somebody else. That's magic. Where else but fiction can we achieve that?

West of Here is a huge, ambitious novel, spanning 100 years and embracing hundreds of fully realized characters. Where did the idea and inspiration come from?

Clams.

No, really! Actually, I wanted to write a history of the Olympic Peninsula, a

place near and dear to me. I spend an awful lot of time hiking and camping in

the Olympics, making frequent stops in Sequim, and Port Angeles, and Forks. I

live for these getaways. My old Dodge motor home allows me to basically live on

the road. While researching in earnest, I was conceiving something along lines

of a historical novel, but I soon realized that what I really wanted to write

was a novel about history, about the countless tiny connections that bind

people together, and tie people to a place, and a time, and how the sum total

of all these connections amounted to a living breathing history. I wanted to

bring the place to life on the page, like Steinbeck brought central California

to life, or Twain brought the Mississippi to life.

Clams.

No, really! Actually, I wanted to write a history of the Olympic Peninsula, a

place near and dear to me. I spend an awful lot of time hiking and camping in

the Olympics, making frequent stops in Sequim, and Port Angeles, and Forks. I

live for these getaways. My old Dodge motor home allows me to basically live on

the road. While researching in earnest, I was conceiving something along lines

of a historical novel, but I soon realized that what I really wanted to write

was a novel about history, about the countless tiny connections that bind

people together, and tie people to a place, and a time, and how the sum total

of all these connections amounted to a living breathing history. I wanted to

bring the place to life on the page, like Steinbeck brought central California

to life, or Twain brought the Mississippi to life.

The characters in West of Here, especially those from 1889, are fictional inventions, though they live and breathe so believably. Where did they come from and what kinds of research did you do to make them so real?

Nabokov likened his characters to galley slaves, as though they were instruments of his will. For me, it's quite the opposite. I create characters so that I can inhabit them, so that their wills can lead me on a journey, not vice versa. I want to empathize with my characters--and how am I to do that, unless I let them make their own decisions, unless I smell the world through their nostrils? I offer them a set of conditions and circumstances, and let them bumble and grope their way through the mess, and I go along for the ride. And when it's over, I feel like a more expansive and understanding person for having undertaken the experiment.

The key to the research in terms of familiarizing myself with the cultural and physical conditions of the Washington frontier (without sounding researchy) was to seek out material that wasn't historicized by a wide-angle lens. What I wanted was personal perspective, rather than historical perspective--personal narratives, letters, oral accounts, anything vivid and descriptive that wasn't bogged down by the omnipotent voice of "history."

Did you develop a

method for keeping track of such a huge cast of characters living in two

very different time periods?

Did you develop a

method for keeping track of such a huge cast of characters living in two

very different time periods?

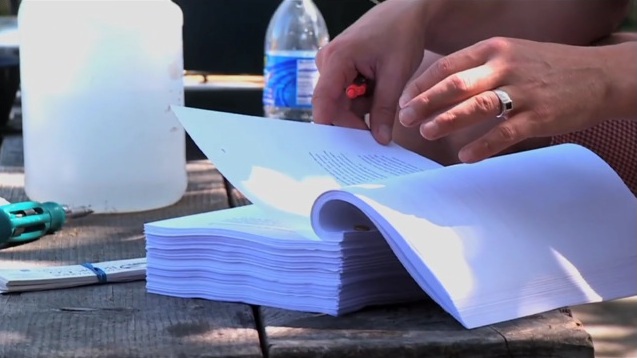

I filled notebooks, I wrote on walls, I printed the manuscript in thick paper so I could color-code the spine. I ran for the hills, clutching stacks of graph paper and bundles of Sharpies. I was a madman. I slept very little, and looked for solutions at the bottom of beer bottles as I scratched out thought-maps and the like, and tried to make sense of my hieroglyphics in the morning (a highly underrated methodology, truth be told).

Each of your characters has such a clear, unique voice. Do you think that your tour of duty in radio, especially talk radio, fine-tuned that skill for you?

The only thing that hot talk radio inspired me to do was write 10 times harder, so that hopefully I'd no longer have to look through the glass at some beady-eyed souljacking producer, typing things like: "Ask her if she's hot?" on the tele-prompter three hours a day. I found the culture of hot talk radio to be suffocating. I think working in a film factory, or landscaping, or hacking up roadkill at the wildlife refuge offered me more insight into character than working in commercial radio, where they were always trying to reduce character to a demographic.

When you relocated from Los Angeles to the Pacific Northwest, you traded one kind of climate (many consider it ideal) for the one you capture so vividly in West of Here. Was there much of an adjustment before love of wildly erratic weather patterns set in?

I hated the climate in L.A. I find that it's a heck of a lot easier to write when you're looking out your window at mud puddles. Sun makes me restless. It makes me feel like I should be outdoors drinking margaritas--and that's too much temptation for me to overcome with any regularity. I'd still be writing Lulu.

As the solitary writer prepares for a book-signing and reading tour in support of West of Here, are you dusting off the audience-courting chops you developed during your days as frontman for the band March of Crimes? Will you sing on this tour?

I never sang in the first place. But maybe I'll scream a little, if it'll sell books. And if by courting the audience, you mean jumping on top of them, we shall see. Maybe a little stage-diving is just what the book tour scene could use.