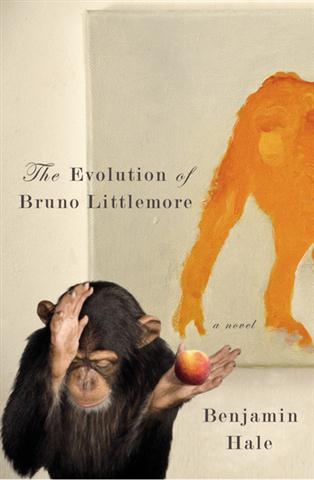

"My name is Bruno Littlemore," the narrator of Benjamin Hale's debut novel begins: "Bruno I was given, Littlemore I gave myself, and with some prodding I have finally decided to give this undeserving and spiritually diseased world the generous gift of my memoirs." Bruno dictates his life story from an institution where he's been confined "due to a murder that I more or less committed," but he stays active: he's directing the other residents in an amateur production of Georg Büchner's Woyzeck, a character with whom he greatly identifies. In case you're unclear how brilliant he is, his other favorite literary icons include Milton's Satan, Shakespeare's Caliban and Pinocchio. Yes, Bruno is a philosophical actor, an eloquent alcoholic and an unrepentant killer. He is also a chimpanzee.

"My name is Bruno Littlemore," the narrator of Benjamin Hale's debut novel begins: "Bruno I was given, Littlemore I gave myself, and with some prodding I have finally decided to give this undeserving and spiritually diseased world the generous gift of my memoirs." Bruno dictates his life story from an institution where he's been confined "due to a murder that I more or less committed," but he stays active: he's directing the other residents in an amateur production of Georg Büchner's Woyzeck, a character with whom he greatly identifies. In case you're unclear how brilliant he is, his other favorite literary icons include Milton's Satan, Shakespeare's Caliban and Pinocchio. Yes, Bruno is a philosophical actor, an eloquent alcoholic and an unrepentant killer. He is also a chimpanzee.

The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore charts Bruno's remarkable development, plucked from the primate house at the Lincoln Park Zoo and sent to a University of Chicago laboratory where he is run through constant behavioral experiments intended to demonstrate that he has the capacity to understand human language. As one of the scientists, Lydia Littlemore, takes the chimpanzee into her home to provide full immersion into a human lifestyle, however, his ability to speak grows as well--although this is kept hidden from the public and even the other scientists, as is (at least as first) the increasingly romantic relationship between researcher and subject. No matter how intelligent he becomes, however, Bruno is still prone to raw emotional outbursts, the consequences of which will force him and Lydia into exile from Chicago; send him fleeing to live as a vagabond actor in New York City; and ultimately drive him to that long foreshadowed murder (and though you may be able to guess the victim, the motive will likely yet surprise you).

Obviously readers are asked to accept significant implausibilities along the way. Among the greatest of these is the relative swiftness with which Lydia shifts into an affair with Bruno after their first, unexpected sexual encounter. (Unexpected to her, that is, but not to the reader, as Bruno has already rhapsodized heavily about his erotic fixation on human women, and there have been warning incidents.) The incident serves as a reminder of how little we really know about Lydia; Bruno's personality is so strong that other characters often become merely the backdrop against which he soliloquizes. This is deliberate to some extent, as Hale uses Bruno's emotional obtuseness for ironic effect throughout the novel, even as he includes philosophical digressions bringing the chimp's outsider status to bear on human nature. However, the downside of saying that Bruno, for all his mental and artistic advancement, doesn't fully "get" humanity is that the humans, as viewed through his perspective, can seem less than fully formed. Intellectually readers can piece together the clues to Lydia's backgroun--the story that makes it plausible a woman would turn to a chimpanzee for emotional and sexual sustenance--but what happens to her can feel less like a tragedy than the idea of a tragedy.

That doesn't make Bruno's tragedy any less compelling, though. Ultimately he is not just a prisoner physically, but existentially, too: "I know that I am not fit to live in human society," he confesses, but "I cannot unlearn my humanity." All that remains is the frustration and rage of thwarted ambition and shattered dreams--an unusual but still resonant depiction of an all too human condition.--Ron Hogan

Shelf Talker: Rick Moody's The Four Fingers of Death also coincidentally features a chimpanzee who receives the dubious gift of human intelligence; more important, Hale and Moody's narrators are both infatuated, if not obsessed, with the power (and limits) of language to carry their emotional burdens.