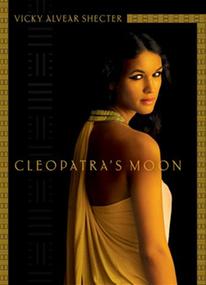

Cleopatra's Moon by Vicky Alvear Shecter (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, $18.99, 9780545221306, 368p., ages 13-up, August 1, 2011)

As the novel opens, 16-year-old narrator Cleopatra Selene sails on a Roman ship bound for Africa. Her twin brother, Alexandros Helios (whom Cleopatra calls "the sun to my moon"), has died during the voyage because, just prior to their departure, he drank from a poisoned cup intended for her. "I stared at the sea," Cleopatra says, "trying to understand how I came to be here. A motherless daughter, and now a brotherless sister. How was it that I went from a Princess of Egypt... to a prisoner of Rome?" The author thus sets up the framework of the novel, as the teen reflects on her past and fears what lies ahead for her. The heroine's position and circumstances in history may be unique, but her emotions as a teen on the cusp of adulthood are universal.

Shecter then flashes back to a pivotal scene when Cleopatra Selene, at age seven, took part in a ceremony in Alexandria, Egypt, at which her father, Marcus Antonius, made his "Dispositions of War." The event not only portrays the man's power, but also the tensions between him and his native Rome. As he bequeaths land to each of his children, he stirs up controversy with his gift to Caesarion, Queen Cleopatra's only son with her first husband, Julius Caesar. Whispers run through the crowd of a name the girl does not yet recognize: Octavianus. What would Octavianus say about these gifts? Is not Octavianus the rightful successor to Julius Caesar? The author skillfully sets up from the beginning the conflict that will influence the course of Cleopatra Selene's future.

We also see lighter moments--Cleopatra Selene's proficiency at the game of trigon ("I have beaten the king of Egypt," she says, teasing Caesarion) and her jealousy when her brothers receive Eye of Horus gifts from their mother, not realizing the significance of her own gift (a golden scarab pendant with an emerald in the center). These endow the weightier moments with greater significance. In one standout scene, the children's tutor, Euphronius, takes them to visit the Jewish Quarter in Alexandria. As their teacher explains, the queen "does not force them to act against their faith, thus earning their devotion and allegiance." They meet Rabbi Yoseph ben Zakkai, who encourages their questions, and Cleopatra Selene discovers the concept of "free will." The rabbi explains, "It is the discernment--the knowledge of good and evil--that is at the heart of free will." This idea takes hold in the young heroine. Even after the deaths of her parents and her forced move to the house of her enemy, Octavianus, in Rome, Cleopatra Selene evaluates the choices remaining to her within a course of events seemingly determined by fate.

We also see lighter moments--Cleopatra Selene's proficiency at the game of trigon ("I have beaten the king of Egypt," she says, teasing Caesarion) and her jealousy when her brothers receive Eye of Horus gifts from their mother, not realizing the significance of her own gift (a golden scarab pendant with an emerald in the center). These endow the weightier moments with greater significance. In one standout scene, the children's tutor, Euphronius, takes them to visit the Jewish Quarter in Alexandria. As their teacher explains, the queen "does not force them to act against their faith, thus earning their devotion and allegiance." They meet Rabbi Yoseph ben Zakkai, who encourages their questions, and Cleopatra Selene discovers the concept of "free will." The rabbi explains, "It is the discernment--the knowledge of good and evil--that is at the heart of free will." This idea takes hold in the young heroine. Even after the deaths of her parents and her forced move to the house of her enemy, Octavianus, in Rome, Cleopatra Selene evaluates the choices remaining to her within a course of events seemingly determined by fate.

"You have the heart of a great and powerful queen." This is the last thing her mother says to Cleopatra Selene. In one situation after another, the teen wonders what her mother would have thought or advised her to do. It's challenging enough as an adolescent to figure out who you are becoming as an adult. It's harder still as the daughter of a great queen who's no longer there to guide you, and whose reputation has been sullied by a Roman leader anxious to enlarge his kingdom and power base. Cleopatra Selene falls in love with Juba, whose situation resembles her own. The Romans killed his father, a king, then raised Juba in the Octavianus household. At one point, Juba tells her, "The important question is not 'Why was I saved?' but 'What will I do with the life that the gods decided to spare?' " Juba's question haunts her as much as her mother's last words do. She feels torn between her love for Juba and the possibility that a match with Marcellus, Octavianus's nephew and chosen heir to Rome, could lead to her return as queen of Egypt. What will she decide? And does her decision matter when Octavianus steers so much of her destiny?

Shecter smoothly balances historical intrigue with classic adolescent romance and abundant details of life in Egypt and Rome--the food, smells, sounds and sights. Key scenes early on establish Cleopatra Selene's sense of confidence and curiosity, as well as the high respect accorded to women in Egypt versus their second-class status in Rome. The author throws some curve balls in the plot's development but, as rereadings will divulge, she plants subtle indicators all along the way. Scrupulous and generous endnotes reveal where Shecter either diverged from the facts or took liberties to fill in missing information.

Shecter smoothly balances historical intrigue with classic adolescent romance and abundant details of life in Egypt and Rome--the food, smells, sounds and sights. Key scenes early on establish Cleopatra Selene's sense of confidence and curiosity, as well as the high respect accorded to women in Egypt versus their second-class status in Rome. The author throws some curve balls in the plot's development but, as rereadings will divulge, she plants subtle indicators all along the way. Scrupulous and generous endnotes reveal where Shecter either diverged from the facts or took liberties to fill in missing information.

If you grew up (as this reader did) lapping up everything about ancient Egypt--its people, their gods, the sense of ceremony, the pyramids, the burial rituals--this book will reignite a sense of astonishment that this culture, so advanced, existed thousands of years before our own. For teens, it serves as a powerful reminder of how the questions so central to becoming an adult cross every line of class, era and culture.