|

|

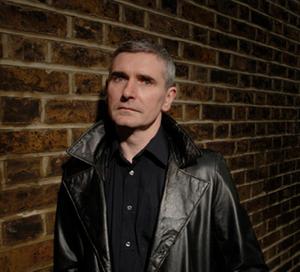

| photo: Charlie Hopkinson | |

M.R. Carey is an Oxford-educated Liverpool native who has been writing comics since the early 1990s. In addition to writing for DC and Marvel Comics, he is a screenwriter and the author of several novels, including the critically acclaimed The Girl with All the Gifts, published in 2014. His new novel is Fellside.

How did the experience of writing Fellside compare to your other work? Did this feel like much of a departure, or were you working in a relatively comfortable mode?

It felt quite new. I was trying to fuse together a very realistic prison novel with a supernatural fantasy about ghosts and the power of dreams, and it felt like that called for a different approach and a different voice than I'd used in Girl. It does still use multiple points of view, which the story seemed to need, but in every other respect it's very much its own thing. Very dark, emotionally very raw and brutal in places, but with an ending that allows us some very hard-earned comfort.

Fellside Prison is a very striking setting. What kind of research did you do into private prisons and women's prisons?

It's been a long process, and as with Girl it's been a kind of composite in that I've been working on a movie version of the story alongside the novel. As the treatment for the movie screenplay came together I did a lot of primary research with Camille Gatin, the producer, and director Colm McCarthy. We met with a senior psychiatrist who is the clinical lead for drug awareness and response in one of the London boroughs, and through him we were able to make contact with his counterpart at a major women's prison in the U.K. We toured the prison and talked with some of the inmates. We went to open meetings of Narcotics Anonymous. All of these things fed into the creative process quite late. In a sense I was filling in the fine detail around an emotional core that didn't change much at all.

Addiction seems to be the single most powerful villain in the book, across the board. Did you set out to write about addiction?

Yes--addiction and dreams. I've known a lot of addicts, some of them people who were very close to me and very much a part of my life. I've seen how it works, and what it does both to addicts and to the people who love them. In a way, it's a subject I've been steering clear of for a long time, and it felt like it was time to see if I could go there.

But the dream side of the story is equally important. There's an idea in the book of the dream state as a sort of collective human property or territory, and there's also the idea that it shares a border with death. I think it was Tennyson's In Memoriam that put that idea into my head. When we dream, the things that bubble up come from different depths in our mind. Some are just the detritus of the day. Others come from so deep they're not really ours. They belong to the bits of our brain that are pre-human. I wanted to have my protagonist trying to navigate that space with her waking mind.

In what ways do you think agency and addiction interact in the context of crime and punishment?

That's such a complex question. Drugs are everywhere in prisons, of course, and they're a massive part of the prison economy. Arguably the drug empire I depict in Fellside is slightly exaggerated, not in terms of its scale but in terms of its complexity. You wouldn't need to have the massively decentralized network of convicts and guards that Harriet Grace uses. You'd just need a couple of bent warders and a friend on the outside. But I don't feel that I exaggerated the scale of the problem. Drugs are probably the biggest source of control problems in prisons. And they're the third biggest source of prisoner deaths, after suicide and heart disease.

And, of course, the grim flip side of all this is that many people come into prison clean and come out as addicts. Drugs are very easy to get hold of, and the more stressed and unhappy you are the more tempting they become. It's a live issue, and there are a lot of debates going on about how best to handle it.

So I think the answer to your question is that drugs add a level of complexity to the prison equation that's very hard to define or quantify. Prison life is always hard. Addiction makes it harder.

Was there a particular reason you chose to write Fellside about a women's prison? Did you ever consider a different gender dynamic for the story?

Those addicts I referred to earlier, the ones who were very close to me--they were all women. So I think Jess was probably always going to turn out to be a woman. That's not to say that I based Jess on people I actually know. I drew on the experiences of those people, but she's not an alias for anybody.

The other thing that's going on here is that I went into a phase of writing stories with female protagonists five years ago, with The Steel Seraglio, and I'm still in it. I don't know why that is, but it seems to be a thing for me right now. I'm not a gender essentialist. I think human kit is mostly interchangeable. But almost everything in our society is gendered and our stories are no exception. Fellside would read very differently if all the key roles were enacted by men.

What kinds of redemption were you interested in portraying in Fellside?

It's a tricky and subjective concept, and I think it tends to fall into the category of things that you don't know until you see them. We look for redemption in all kinds of unlikely places. But it comes, if it comes at all, on its own terms. We can try to buy it or to build it, but all we're really doing is building a nest-box and hoping it will come. In plain terms, I think we make accommodations with our own worse and better selves. All the time, in all kinds of ways. Redemption is part of that process. --Emma Page