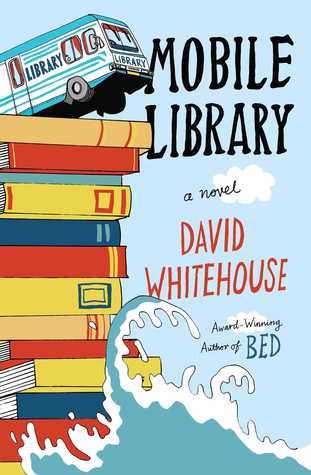

David Whitehouse is a novelist, journalist and screenwriter. His first novel, Bed, winner of the 2012 Betty Trask Prize, has been published in 18 countries. His second novel, Mobile Library, is the story of an unusual family's adventurous roadtrip in a truck full of books (our review is below). He has several TV and film projects in development with Film4, Warp, the BBC and others. He writes regularly for the Guardian and the Times, and is currently editor-at-large of ShortList magazine. Whitehouse once made a joke about Lance Armstrong on Twitter that was retweeted 10,000 times.

David Whitehouse is a novelist, journalist and screenwriter. His first novel, Bed, winner of the 2012 Betty Trask Prize, has been published in 18 countries. His second novel, Mobile Library, is the story of an unusual family's adventurous roadtrip in a truck full of books (our review is below). He has several TV and film projects in development with Film4, Warp, the BBC and others. He writes regularly for the Guardian and the Times, and is currently editor-at-large of ShortList magazine. Whitehouse once made a joke about Lance Armstrong on Twitter that was retweeted 10,000 times.

Sometimes career journalists transitioning to novel writers have trouble letting go of facts in order to embrace fiction and imagination, but that was not the case with David Whitehouse. He says, "My journalism was, still is occasionally, very verbose, very flowery. I was never reporting on war zones or crime or anything serious. I was interviewing film stars and bands and things like that. Experiences in reality are often quite boring and I found myself exaggerating or writing for my own amusement as though I was writing a story. Obviously, in journalism you can't do that, it's really bad. That's why I was a bad journalist. Writing fiction was a release where I could forget about fact-checking and hard-core research, the things I never really enjoyed."

And this approach has worked splendidly for the author of two novels and many scripts. There was one small blip in the process: Whitehouse's rocky trek to publish his first novel, Bed. A trek that almost discouraged him from writing again.

After completing Bed, Whitehouse quickly found an agent willing to represent his manuscript. Finding the publisher, however, was not so easy. After many rejections, Bed moved to his agent's desk drawer, where it sat for two years. It might still be there if not for To Hell with Prizes, a contest for unpublished manuscripts. Bed won the award and the attention of one of the judges, Canongate's publishing director. The validation reinvigorated Whitehouse and found Bed its rightful audience: "I'm of the opinion that people never really know what they're looking for until they see it or read it. In winning the prize it found someone who liked something in it. Had it not won the prize, it would never have been published. And I probably wouldn't have written anything again, at least for a long time. Certainly not by now."

But write again he has, and in grand style. About his debut, Whitehouse explains, "I didn't really know what I was doing, I didn't know if I would ever be published, I didn't really know what publishing was, I didn't even know how long a novel was--I remember Googling, 'how long is a novel?' while I was writing it." He wrote in small snatches of time everyday, what he describes as "that kind of semi-romantic thing."

But the second time around is different. And Whitehouse says he had to wrestle with the process for Mobile Library, keeping regular working hours and treating his writing like a job. "The pressure was on me to prove I could do it again and that I could tell a proper story. Bed is story but not in a conventional sense. Mobile Library is about stories and it's about the form and content of stories and what's hidden in them and what they do to people. So it had to be in every sense a conventional kind of tale. When I sat down to write it, I suddenly realized I'd never actually done that. I was going back to the drawing board and teaching myself about character, plot and pace."

But the second time around is different. And Whitehouse says he had to wrestle with the process for Mobile Library, keeping regular working hours and treating his writing like a job. "The pressure was on me to prove I could do it again and that I could tell a proper story. Bed is story but not in a conventional sense. Mobile Library is about stories and it's about the form and content of stories and what's hidden in them and what they do to people. So it had to be in every sense a conventional kind of tale. When I sat down to write it, I suddenly realized I'd never actually done that. I was going back to the drawing board and teaching myself about character, plot and pace."

Whitehouse can take up teaching if he ever decides to leave writing because he succeeded in teaching himself more than conventions; he taught himself art.

Mobile Library is the story of a young boy who escapes a tragic life with a single woman and her daughter... in a library on wheels. Whitehouse's plan for Mobile Library was to write an adult fairy tale. "The children's books I used to love had really dark hearts to them. And I used to love how those dark hearts were hidden in other things. Even as a child I realized that. In James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl, his parents are eaten by a rhinoceros. When he travels to New York on a big peach, that's his escape, his grieving process from losing his parents. I wanted to try to do that in an adult book."

Another love that Whitehouse weaves into his fairy tale is the idea of the road trip. "I love road trip books and movies; I love the idea of running away and escape. That's what the book represents. A book is a time machine or a teleportation device you can get in in the absence of a real time machine and have a journey or an adventure somewhere else. I wanted this little boy to have a million of those around him, have the opportunity to travel anywhere and do anything while going on a literal journey. I wanted to capture that sense of escape that I got when reading books as a child."

And what better mode of transportation than a truck? "Little boys love big trucks," Whitehouse notes. And the novel's truck is modeled after the mobile library his mother cleaned when he was a child. He describes it as "an articulated lorry--an articulated truck. The biggest truck on the road. It seemed to me to go on forever. It was like a transformer: you'd press a button and a staircase would come down to your feet. It sounds like I'm inventing this, but I'm not. It was really great. I could go in and spend all day in there."

Like Whitehouse, his young hero, Bobby, is also fascinated with the truck. And for good reason. "Bobby probably is me for one specific week in my childhood when I was in that library and wanted to escape. Not necessarily what happens to him, but all of his impulses are mine." And about Bobby's best friend, he says, "Sunny is probably the other part of me that didn't really exist but wanted that capacity for mischief. I was probably a bit too well behaved. I was quite a cautious child so I wouldn't be the one throwing myself off the top of buildings and things. I always admired that in kids that could. I do remember once trying to injure myself so I would be sent home from school. But I was too bad at it; I was too scared to jump off anything."

Interestingly enough, Mobile Library started out much different in early drafts. "There was an earlier draft of the book that didn't have Bobby in it. It was about the adult version of Bobby after all of this has happened visiting his hometown where he was the 'Mobile Library Boy.' " This early version was written in first person, but an omniscient narrator tells the story in the final product. Whitehouse explains this is because "I realized [the story] is wider than that. It's about the four of them coming together--it's the biography of an unusual family, rather than one little boy's story."

Family is a subject that overlaps with Whitehouse's first book. Like that family, Bobby's biological family is detrimental to his well-being. But Whitehouse is quick to clarify, "I'm not saying every family is a destructive force, but we can't pretend we're all the Waltons, can we? It was important to me to reflect that families aren't all perfect; the love that you get and the bonds that you have with them can be discovered in other places. Some people have the Internet instead of family. They don't call up their mother and say they've had a bad day, they tweet it."

Readers will not find any tweeting in Mobile Library, however. While their story might have made for an entertaining Twitter stream, the mismatched family members are all too busy in their grand adventure. Since his first and second books are so unalike in style, what will the third bring for Whitehouse? "I think probably something completely different which is probably somewhere between the two. I think Mobile Library dictated the way it was written; so did Bed, actually. I think I'll probably be led down the path by the idea." --Jen Forbus of Jen's Book Thoughts

David Whitehouse: Following the Ideas on a Road Trip

What are the tradeoffs of immortality? How many people whom you love would you outlive? What would it be like to "stay seventeen till the end of the world," as Jesse Tuck does? For the 40th anniversary of the publication of Tuck Everlasting, Farrar, Straus & Giroux created a special edition that closes with an interview with Natalie Babbitt. "The question of what it might be like to live forever is something that everyone thinks about," she says. "And I think you think about it more when you find out you can't do it." Babbitt explains that she created the four Tuck family members "specifically to talk about different points of view of living forever." She makes us think about what is precious, and what is made more so because we know it cannot last.

What are the tradeoffs of immortality? How many people whom you love would you outlive? What would it be like to "stay seventeen till the end of the world," as Jesse Tuck does? For the 40th anniversary of the publication of Tuck Everlasting, Farrar, Straus & Giroux created a special edition that closes with an interview with Natalie Babbitt. "The question of what it might be like to live forever is something that everyone thinks about," she says. "And I think you think about it more when you find out you can't do it." Babbitt explains that she created the four Tuck family members "specifically to talk about different points of view of living forever." She makes us think about what is precious, and what is made more so because we know it cannot last.

David Whitehouse

David Whitehouse  But the second time around is different. And Whitehouse says he had to wrestle with the process for Mobile Library, keeping regular working hours and treating his writing like a job. "The pressure was on me to prove I could do it again and that I could tell a proper story. Bed is story but not in a conventional sense. Mobile Library is about stories and it's about the form and content of stories and what's hidden in them and what they do to people. So it had to be in every sense a conventional kind of tale. When I sat down to write it, I suddenly realized I'd never actually done that. I was going back to the drawing board and teaching myself about character, plot and pace."

But the second time around is different. And Whitehouse says he had to wrestle with the process for Mobile Library, keeping regular working hours and treating his writing like a job. "The pressure was on me to prove I could do it again and that I could tell a proper story. Bed is story but not in a conventional sense. Mobile Library is about stories and it's about the form and content of stories and what's hidden in them and what they do to people. So it had to be in every sense a conventional kind of tale. When I sat down to write it, I suddenly realized I'd never actually done that. I was going back to the drawing board and teaching myself about character, plot and pace."