|

|

| photo: Suzanne Reiss | |

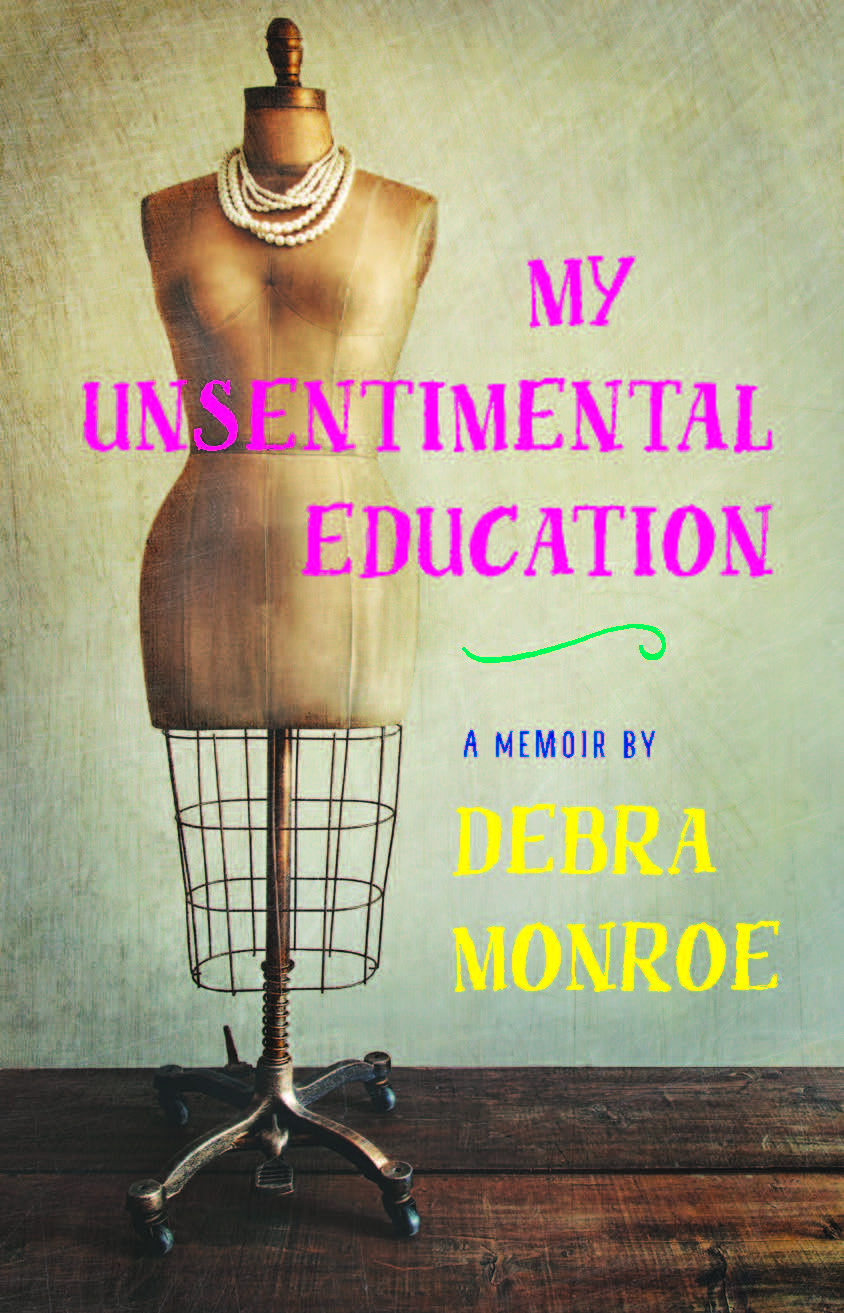

Debra Monroe was born in North Dakota, raised in Wisconsin and has since lived in Kansas, Utah, North Carolina and Texas, where she now teaches in the MFA program at Texas State University. In 1990, she won the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction. In addition to four works of fiction, she has published poems, stories and essays in many magazines and journals. Her first memoir, about being the white mother of a black daughter in a small Texas town, On the Outskirts of Normal, was published in June 2010. Her new memoir, My Unsentimental Education, has just come out from the University of Georgia Press (October 2015, $24.95).

It's a linear narrative for the most part, with some delightfully quirky segues, witty descriptions ("dating a boy who rambled either because he was tripping or he'd read Rilke") and lyrical prose. Monroe writes with exuberance of a life filled with drama, heartache, obstacles and joy. Annie Dillard provides the book's epigram: "I am aging and eaten and have done my share of eating too." It's apt for Monroe, who has certainly done her share of eating, and being eaten.

You became an adult during a time of great societal change, especially for women, and you're so eloquent about your longing to be somebody, to be something other than a wife.

Yes, even though I wanted that, too. Feminism (at that time it was called women's lib) was about women not having to choose either/or. That made me a reluctant feminist in the beginning. It felt like you had to say you didn't want to be a mother or you didn't want to come home to someone at night who loved you, and I wasn't willing to say that when I was younger. But I also think that the message got a little twisted, as these things tend to do--women's lib wasn't about having it all, it was really about choices and not being shunted down a certain path.

I try to tell my students now, young women, that we were just making it up. No one knew what to do and what to do with ourselves. The sexism I didn't even blink at--some of it was what we'd call sexual harassment now. I felt almost apologetic that I was a woman and I wanted these things.

It was hard pushing forward academically, professionally--a PhD and getting tenure, all of that, is still very hard--but it was especially daunting in that era for women. (Because we had to seem to be just like men, or so the implicit message was.) My professional life took about 80% or more of my attention. And when I'd stop to consider whether my private life was in good shape, I'd acknowledge to myself it wasn't. But then my attention would return to another deadline, another class to teach, another milestone to reach to get a secure footing. It's about what we now call "work-life balance": I didn't have it. I had work mostly, with life decisions stuffed in on the side. I mention this in the "In the Event of an Apocalypse" chapter when I'm talking to the Mormon therapist: everyone in school tried to settle the romance question fast and get back to work, because we couldn't afford to spend any more time on romance/happiness questions.

You believe without public education, you'd be a small-town waitress, "haughty with boredom." Instead, you found yourself a role model for your female students, who probably thought you had your life planned out. But you later say your career happened by accident. What part was accidental?

You believe without public education, you'd be a small-town waitress, "haughty with boredom." Instead, you found yourself a role model for your female students, who probably thought you had your life planned out. But you later say your career happened by accident. What part was accidental?

I broke up with my high school boyfriend in order to go to college, but then I was afraid to go to college so I ran away to Colorado with a guy who was wanted in Indiana. I was sitting at home watching daytime TV, minding a third grader, while my husband worked. So I came back to Wisconsin and was a waitress, and thought: now I'd better go to college. And I did. But nothing practical! A BA in English with no teaching credits. So the next thing was an MA in rhetoric, with the plan of eventually teaching at a junior college. But my first husband left before I finished that degree, and I thought, well, as long as it's not going to inconvenience anyone, meaning my husband, I could get a PhD. And then I married my second husband--not a good marriage. In the last year of my PhD program, I won the Flannery O'Connor Award--in the nick of time. Now I think if I hadn't won that award, then I would have been stuck teaching as an adjunct for years, married to a wife beater. I moved to North Carolina, to a prestigious school, then I took this job in Texas to save the second bad marriage, but he didn't come with me. I'm here now, happily. So as for career trajectory, it was always if Plan A fell through, then Plan B kicked in. None of my Plan As--the relationships--lasted. So I made a career by accident. Had I not had so many bad relationships and marriages, I wouldn't have felt free in that era to pursue higher education.

And yet you couldn't get rid of the idea of being the "angel in the house."

That's not really gone. It's a huge part of my identity. It really confronts me. I'm very good at small repair, power tools, because I grew up going to shop class and built my own house in Texas. But I remember my mother, who was my father's bookkeeper full time, and she kept such a clean house, she made dinner with all the food groups every night. I think of that very fondly and I'm happy when I'm doing it for my own family. I just am. So I really am both a housewife and a career woman. And it's certainly gotten easier.

As time passed, the distance between your "daytime self" and "nighttime self" widened. Did that contribute to your feminism?

Day life and night life... the distance got wider and wider, and it was a sort of a wake-up call that for the longest time I used to think that my real self was Debbie from Spooner, Wisconsin, not Dr. Debra Monroe, professor and author. I assumed that if I wanted to relax at night or on the weekends I needed to be my real self, and it just didn't click for the longest time that my real self wasn't my childhood self, that finally you are who you become, not who you used to be. It's not related so much to feminism as to comfort zone, not being apologetic about liking to cook, etc. And I've had the hardest time being attracted to men who couldn't use power tools or change spark plugs, because I can. Now I'm married to a man who can do little engine things, and mow the lawn, but I am much better at household repair than he is. I got over it to some degree.

"Reading, more exciting than life, calmed me." That sounds contradictory.

It does. But reading is like a really good drug. It blocks the bad stuff, keeps you alert. It really does calm me down. It's still my main shore for situational depression or overstimulation or the flu or whenever I feel like I just need a break from real life. Nothing else works. Exercise helps a little, but to lose myself in a book... you stop being yourself. You enter another life, another time, somebody else's set of problems. It's vicarious. It's not your life. Experiences you'd prefer not to have, but you're still learning about life.

My first choice for reading is not something searing and hard-hitting. I tend to avoid books when I'm really busy, because I'll stop doing everything. I'll find myself saying, "If I don't wash my hair today I can read another 20 pages...." It's totally addictive for me. My drug of choice. I like movies, TV, but I'm not neurologically wired for them.

And it's so much more private to read. I lose the world.

At one point, you write that you cultivated short-term affections: "high-risk, high-reward." Then you adopted Marie. You "gave up the wild life." You could forgo marriage, but not motherhood. Has your life as a mother been what you wanted?

Absolutely. It's the most important, most satisfying... I don't know how to say it. It's the best thing that's ever happened to me, and it's mostly been fun, even the hard parts were really, really interesting. And she's just a fantastic kid. A happy kid. She looked happy when she was two days old. And also, when you raise a kid, you instill their sense of humor, or they inform yours. Sometimes when I am trying to be serious, she can get me laughing so hard that I lose control. She's pretty wonderful. She's not attracted to the dark side like I was.

With your last marriage, to a lawyer, you say that you were playing a role: "last self." Do you mean your latest self, or your final self?

That was at his retirement party seven years ago, where I was meeting his colleagues. I still had a little bit of imposter syndrome. I'm not going to say that I'll never be another "self," but we're well-suited for each other. He's a great father, it feels really like I belong here. I can't see any radical transformation--I was a country-western singer's wife, then dressed like Greta Garbo, then like golfers in North Carolina, then when I first got to Texas I was overly influenced by Lucinda Williams. But now I feel like myself. I also feel like I've come full circle. I've gotten the best of my mother's values--they are in this marriage--and the worst of that generational stuff isn't here. But the "angel in the house" parts that I did like are here. And I'm really in love. Besides, we're too old to split up. --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers