|

|

| photo: Lisa Brooks | |

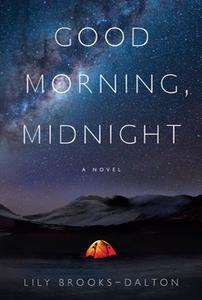

Lily Brooks-Dalton is the author of the memoir Motorcycles I've Loved, a finalist for the Oregon Book Award. Her debut novel, Good Morning, Midnight (Random House; reviewed below), is a twist on the literary post-apocalyptic novel, drawing comparisons with Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and California by Edan Lepucki. Good Morning, Midnight is purposefully vague about the exact nature of its apparent world-wide calamity, focusing instead on its two protagonists and how they cope with isolation. Brooks-Dalton takes us back and forth between Augustine, a scientist left (almost) alone in a remote Arctic outpost, and Sully, an astronaut making the long return journey to Earth. Gradually, the stories intersect in surprising and emotional ways.

Do you consider Good Morning, Midnight to be a post-apocalyptic novel? You reveal remarkably little about what apocalyptic event might have occurred--what led you to such an interesting narrative choice?

I do consider it a post-apocalyptic novel, but perhaps some might disagree for the reason you mentioned. I think in many ways we as a society are attracted to post-apocalyptic fiction because we sense that an ending to our own reality is imminent. To me, whether that ending comes in the form of epidemic, climate change or war, seems (in the context of this project at least) to matter so much less than the outcome itself. I love all kinds of post-apocalyptic fiction, but in this novel I wanted to keep the focus on the characters. Letting the mystery of what has happened to civilization linger seemed to reinforce that emphasis, but also to create tension--in the end, you do get a piece of mystery revealed, but it's not perhaps the mystery you were expecting.

You refer to a few classic science fiction novels in the book, including Childhood's End by Arthur C. Clarke and The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin. Where do you place your novel in relation to the genre? What is your view of melding or bridging genre distinctions?

Not really. I love it all. I love that people are interested in talking about these different genres and how they might blur together or diverge, whatever the case may be, but my interest lies in enjoying others' work and writing my own, without really giving genre distinctions much thought. I loved and admired the novels I mentioned in the book but I also thought that my characters would be attracted to them as well, so that's why I included them.

Your novel features parallel stories unfolding in the Arctic and in space. How did these two distinct, seemingly separate stories wind up becoming a single novel?

They were always intertwined in my head. The fact that the stories spend so much of the novel running parallel without connecting seemed like a good way to portray the isolation of both narratives, and their ultimate connection spoke to what I see as the fleeting and imperfect, yet vital, role that connection plays in those characters' lives. In all of our lives, really.

Sully and Augustine are both lonely, isolated people even before the unnamed cataclysm occurs. At times, Augustine even seems relieved to be on his own--that is, aside from Iris, his mysterious (and practically mute) young companion. Is there a sense in which you're giving these characters what they secretly want--true isolation--and having them discover the consequences?

Oh, definitely. The coziness of being alone and the jagged edge of isolation are two extremes that I think about a lot in my own life. Part of what interests me about that is how both of these absences can look so similar--it's really the interior experience that separates one from the other. In the novel, I wanted to use an external isolation to expose an internal absence, and to play with that contrast of inner/outer experiences of isolation/solitude. But I think you make a good point about the characters getting what they secretly want and then struggling with the unforeseen consequences of that.  Your characters are connected by their shared astronomical interests. Why choose fascination with space as a unifying theme? Does it derive from your own interest in the subject?

Your characters are connected by their shared astronomical interests. Why choose fascination with space as a unifying theme? Does it derive from your own interest in the subject?

I liked the mirror of Augustine looking up/out into space, and Sully looking down/in at Earth, but I also did want to explore my own fascination with astronomy, and what better way to do that? I did quite a bit of research, though I'm sure I still got some things wrong, because I wanted the settings to feel accurate and not at all fantastical. A lot of the research didn't make it into the book, actually, but it informed the story, and I had a terrific time flipping through astronomy books or trolling the Internet for interesting facts. Space.com was my homepage for quite a while, just so that every time I opened my web browser my mind was instantly on space.

A lot of the action in Good Morning, Midnight plays out psychologically rather than physically. How do you tell a story where the conflicts are rarely external without relying solely on introspection? How did you balance your desire to delve into the characters' stories with the need to move the narrative forward and maintain readers' attention?

It's a tricky balance, for sure. In many ways the landscape itself was a good tool to externalize the interiority of the characters, as I think their experiences are often reflected by the physical space around them. In the end, both of the main characters are on a journey: one is coming home, and another is searching for that home. That motion propels a good deal of the story forward, and the relationships they are cultivating serve that purpose as well.

Thebes, an astronaut on the Aether, says: "We study the universe in order to know, yet in the end the only thing we truly know is that all things end--all but death and time." Along the same lines, Augustine has to learn the hard way that all the knowledge he gathered and the accolades he received are rendered meaningless in the face of humanity's demise. At the same time, you refer to Carl Sagan's Cosmos, a very optimistic take on science and the expansion of human knowledge. Do you find yourself thinking about what pursuits are worthwhile in the limited time we have?

So much of what I love about Carl Sagan is his curiosity. It's a characteristic that I find so invaluable. But a strong desire to learn or know is not the same as knowing. Seeking for answers is not the same as finding them. And so yes, I think that humility and a lack thereof plays a large part in the way that Augustine is portrayed. He isn't curious so much as driven, and when those rock-solid accomplishments become meaningless there is nothing beneath that sense of accomplishment and pride. His motivation reveals itself as overinflated ego.

So, yes, I do think a lot about what is worthwhile. All things end--but I don't believe that should create passivity or hopelessness if we're making the most of the time we have. There's so much space to explore between a beginning and an ending. Focusing on those inevitable bookends neglects all the wonderful, terrifying space in between. For this book, I kept coming back to the question of what is left when everything else is gone. The friction of giving a group of scientists this question, of turning an intellectual pursuit into an emotional reckoning, felt like fertile ground.

A strain of existential terror seems to run through the novel. And yet, there's a warmth and hopefulness among your small group of characters. How do you tell a story involving the possible end of human civilization without veering into nihilism and despair? How do you make sure relationships and character growth feel consequential against such an epic backdrop?

I thought about this a lot, but in so many ways examining the question of what is left when everything else is gone casts a glow around the things that remain, however bleak the void that surrounds those things may be. On the other hand, despair is part of the human struggle, and without despair there is no hope. It's with this give and take, the way that the most horrible things can often yield the most beautiful, that I tried to navigate the circumstances of this novel. And in terms of whether or not relationships matter against an infinite expanse--it matters to the people experiencing them, and that has to be enough. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books