|

|

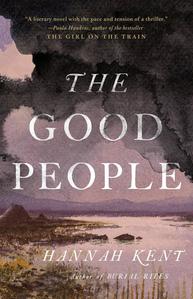

| photo: Lauren Bamford | |

Hannah Kent is co-founder and publishing director of the Australian literary publication Kill Your Darlings. Her first novel, Burial Rites, was shortlisted for the Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction. In The Good People (Little, Brown), she has crafted a historical novel of pre-famine Ireland. Kent lives in Australia.

Like Burial Rites, you found inspiration for The Good People in a true story. What draws you to crafting stories around these pieces of history?

I think I'm drawn to these true stories because they find me as snippets: a small piece of a much larger, absent narrative. It's in the silences, the things that have been left out or left unsaid. Why is so little known? Why has this story been buried?

The Good People is an attempt to answer these kinds of questions. I read a very brief newspaper article from 1826, about a woman called Anne/Nance Roche who had defended herself against criminal charges by proclaiming herself a "fairy doctress" attempting to cure a "fairy struck" boy. My inability to find any ready information about the case only made my curiosity more acute. Did this woman truly believe in the fairies? What did she mean by fairy doctress? What role did she play in her community, and how did this dreadful state of affairs come to pass?

What was your research like for this book? There's so much historical detail, and such a strong sense of place, language and culture woven into the lives of these women.

Given my attraction to stories that are largely undocumented or misrepresented, research allows me to learn more about the world my (undocumented, misrepresented) characters lived in. Not only the big things (political movements, wider historical events), but the minutia of day-to-day living. What might they do on any given morning? What were the social mores of the time? What proverbs would they have been familiar with? Did they wear shoes? How frequently did they eat? My aim is to find out as much as possible--to become saturated with familiarity--so that when I write I can "see" everything.

In the case of The Good People, I spent nearly two years reading everything I could get my hands on about life in rural, pre-famine Ireland. I focused particularly on Irish folklore, reading local histories, novels, diaries, newspapers and books of Irish herbalism. I spent time in Ireland at the National Folklore Collection, and drove all about the country visiting open-air museums, walking the landscape and speaking with academics, librarians, historians and farmers about everything from hiring fairs to cures for warts to Catholic agitation to the best way to kill a pig. It was a haphazard and intensive approach, but fascinating.

It was very important for me to ensure that, no matter how fictionalized the plot, the rituals and herbal cures and sayings included in The Good People were as faithful as possible. In this way, research, for me, became a means of respecting the past, and respecting a culture that is not my own. It's one way I attempt to pay my dues and placate the dead. "Fairy tales" today are often thought of as cute and childlike, but the traditions of the fairies in Irish folklore have a much darker side.

"Fairy tales" today are often thought of as cute and childlike, but the traditions of the fairies in Irish folklore have a much darker side.

It's true that most fairy tales are quite dark. One thing I learned while reading about Irish fairy lore was that fairies were considered neither good nor evil. "Not bad enough for Hell, and not good enough for Heaven," as the saying went. The fear and awe that many felt for them seemed to have stemmed from the belief that fairies were (and, in some places, still are) utterly unpredictable and unguided by a moral code. When someone experienced the inexplicable, the fairies were invoked as explanation. They were believed capable of bestowing great gifts and favors on people, and just as quickly "striking" or inflicting harm on others. It's understandable that people therefore spent a lot of time trying to stay on the right side of the fairies, to protect themselves from their sudden and impulsive malice as much as possible.

One of the things that comes to light over the course of The Good People is a sense of tension between the old and the new. How do you think tension played out in the lives of everyday people like your character Nora?

I didn't set out to set up the "old ways" against the modern world as a source of conflict in the novel, but the more I read, the more apparent it became to me that this was a time of great change in Ireland. Written cultures were replacing the oral; urban places were changing much more rapidly than rural ones; the Catholic church was trying to shed the "pagan" practices (such as the keening at wakes, dancing at crossroads and regard for the fairies) that had hitherto been considered part of the faith, not annexed to it. It was eventually impossible not to include these tensions in the novel.

There was a famous herbalist in Ireland called Biddy Early, who I heard a wonderful story about. A priest, believing her practice to be pagan, forbade the local faithful to go to her for cures, or to tell any visitors where she lived. One day, a traveler came into the village and asked for directions to Biddy's cottage. The locals, out of respect for the priest, told him that they couldn't tell him where she lived, and while they told him this, they pointed him to the path that led to her door. This respect for both priest and "pagan" authority seems to be quite common, and while everyday people were aware of the tension between them, many seemed to find ways to accommodate both old and new well into the latter half of the 19th century.

So many of the characters in The Good People are desperate. How do you think that desperation pushes these characters--indeed, pushes anyone--to such drastic actions?

I think it comes down to a desire for agency. People are usually made desperate due to external circumstances. In the case of The Good People, things like poverty, death of loved ones and social mores and customs rob my characters Nora, Nance and Mary of the luxury of choice. Their lives are at the mercy of their circumstances, none of which they can control, which naturally makes them desperate. The reason they make the choices they do, which are often drastic, is because none of them are willing to live in a state of disempowerment. Action offers them a feeling of agency, of control, and possibility, and so they do things that they might otherwise have not chosen to do. I understand this completely. I think we all do, deep down. None of us knows what we are capable of, if driven to it. But none of us can say for sure that we would not do something equally as drastic if the only other option was to give up entirely. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm