|

|

| photo: Melanie Dunea | |

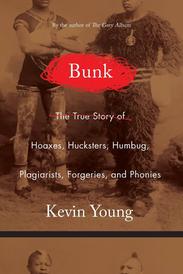

Kevin Young is director of the New York Public Library's Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture and the new poetry editor at the New Yorker. He's published nine books of poetry, edited eight others, and written The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (Graywolf Press), a survey of African American culture that illustrates its tradition of storytelling, improvising and "jazzing." Young is a very busy man; fortunately, not too busy to research and write an outstanding history of American hoaxing: Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News (Graywolf Press, $30). Marlon James calls it a book "we greatly need, disguised as [a book] we merely want."

Young begins Bunk with what he calls "The Age of Imposture," and ends with our current "Age of Euphemism." While he does touch on non-American hoaxing--the Cottingley fairies, for instance--his contention (amply proven) is that the hoax is "an oddly American phenomenon," one way that 19th-century America "sought to establish its bona fides after the fact" by creating tall stories and foundation myths. We are historically programmed for hoaxing, he argues, even more so today; both our doubt and our need for certainty have led to more hoaxes, not fewer.

The Age of Imposture features, appropriately, P.T. Barnum, and what Barnum called "humbug." His audience wanted a show, and was willing to be fooled as it viewed his curiosities. The dark side to Barnum and other historical hoaxes is the extent to which they relied on the exotic and the dark-skinned, and the frissons of fear this "other" produced. Barnum's popularity coincided with the rise of eugenics and racialism, and pseudo-sciences like phrenology, where "objective investigators constantly rediscovered that Negroes, Indians, and other dark races (some of them European, mind you) were indeed still inferior." Barnum stoked the idea of American exceptionalism and white superiority.

Unsurprisingly, many hoaxes employ African Americans--crack babies, inner cities, welfare queens, the war on drugs. Because of this, Young continues, we are primed to believe almost anything about African Americans, especially if it is clothed in respectable writing. Hoaxes "confirm what we suspect... guns are always smoking, buoying up our worst suspicions without evidence or eyewitness."  Fake memoirs, forgeries and plagiarism are all facets of hoaxing. James Frey, with his false memoir A Million Little Pieces, is the perfect example of Young's observation that "Almost all hoaxers, once discovered, go on to write a novel--when it turns out they were writing a novel all along." We lose something with false memoirs--Mary Karr points out that the writers are cheating themselves "out of their real stories." Not to mention cheating readers out of what could be a story all the more powerful for being real and accessible.

Fake memoirs, forgeries and plagiarism are all facets of hoaxing. James Frey, with his false memoir A Million Little Pieces, is the perfect example of Young's observation that "Almost all hoaxers, once discovered, go on to write a novel--when it turns out they were writing a novel all along." We lose something with false memoirs--Mary Karr points out that the writers are cheating themselves "out of their real stories." Not to mention cheating readers out of what could be a story all the more powerful for being real and accessible.

We are now in the Age of Euphemism. Today's hoaxes rely on our cultural amnesia, which enables "alternate facts" and "fake news." The Barnum in the Age of Euphemism is Donald Trump. "The worst of it is that Trump too exploits deep-seated social divisions, ones that, despairingly, echo the very same ones of race and difference on which the history of the hoax has long relied," Young writes. "Little has changed [since Barnum]: race and ruin, devolution and descent, dangerous city life and a noble, now-gone American past become fodder for and are fed by the huckster."

Kevin Young has written a masterful (and massive) book. At 480 pages, it's both scholarly and accessible, angry and witty--absolutely compelling reading, including his 50-plus pages of notes. His sense of humor rarely deserts him: quoting a critic about a poet's worldly advantages, Young writes, "Worldly advantages? He does realize that this is poetry, right?" His precise prose reminds the reader that he is a poet. Young had hoped, when he began, that Bunk would have a happy ending, that we might stop collaborating with the hoax. But our history and our present belie that--"There is of course no larger mass hysteria in American history than the epidemic of racism." He asks, what if truth is a skill, a muscle to be exercised--one that has grown weak? "How might we rebuild it, going from chronic to bionic?" That is a question we all have to answer, and now. --Marilyn Dahl