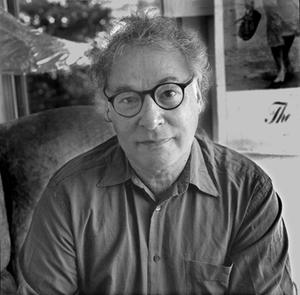

Howard Norman, winner of the Lannan Award for fiction and a two-time National Book Award nominee, is the author of The Bird Artist, The Museum Guard, The Haunting of L, What Is Left the Daughter, Next Life Might Be Kinder and the memoir I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place, among others. He divides his time between East Calais, Vt., and Washington, D.C.

Howard Norman, winner of the Lannan Award for fiction and a two-time National Book Award nominee, is the author of The Bird Artist, The Museum Guard, The Haunting of L, What Is Left the Daughter, Next Life Might Be Kinder and the memoir I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place, among others. He divides his time between East Calais, Vt., and Washington, D.C.

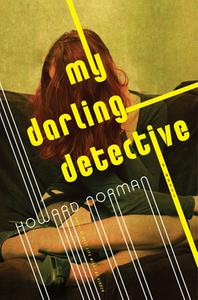

His latest novel, My Darling Detective (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $26, 9780544236103, March 28, 2017), is set in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Norman mixes a present-day mystery (the desecration of a Robert Capa photograph) with one from the past (two murders during a 1945 outbreak of anti-Semitism). While Jacob Rigolet and his police detective fiancée, Martha Crauchet, attempt to unravel both cases--along with the further mystery of Jacob's father--they unwind by listening to episodes of Detective Levy Detects on the radio. The serial is set right after World War II, and lends a noir-ish atmosphere to Norman's beguiling story.

What attracts you to noir?

I like to write characters who, given the right conditions, inadvertently or willfully cross a palpable moral line. Detective Levy, in the radio program Detective Levy Detects, which weaves through My Darling Detective, uses mobsters from an earlier time to solve certain crimes. This time-travel device has allowed me to fold noir of the past into noir of the present.

In classic noir films, there is a kind of floating anxiety, but it can emotionally register very deeply--as Graham Greene said, "even the soul is shadowed down a street." In this new novel, the noirish atmosphere is an intensifying element to the plot--and to the two parallel love stories at the center.

There's some great darkly witty dialogue in Detective Levy Detects. For you, does the present not lend itself to noir wit? Or even to noir?

I sometimes feel our present political atmosphere almost requires a deeper understanding of noir. Of melancholy and anxiousness and the almost desperate need to find some sense of calm deep within one's own life. I didn't want the dialogue between my narrator, Jacob, and his darling detective-fiancée, Martha, to mimic the noir repartee of Detective Levy Detects. However, I did very much want them to be influenced--intellectually and erotically--by the radio. I hope a reader feels that this is true.

In your earlier novel What Is Left the Daughter, radio plays an important part. In this new novel, radio is central. What is the attraction of radios?

My favorite subject! I remember asking my mother how it was to see television for the first time, and she said, "Jack Benny was handsomer on the radio." In My Darling Detective, the idea was quite simple. I wanted the crime drama Detective Levy Detects to provide episodes of intrigue, romance and menace that to some extent retrospectively mirror what Jacob and Martha are experiencing in their contemporary daily lives. I love a line from Virginia Woolf: "Let us turn on the radio and listen to the past."

You use a real photograph--Robert Capa's Death on a Leipzig Balcony--to begin your story. Tell us about that.

You use a real photograph--Robert Capa's Death on a Leipzig Balcony--to begin your story. Tell us about that.

I have an original edition of the photograph on my wall. To me it depicts the ambushing pathos of World War II--an American infantryman just shot by a young German sniper in the city of Leipzig. It was in Life magazine near the end of the war. The photograph haunts me deeply. On the first page of My Darling Detective, Jacob's librarian mother attends an auction where she throws a vial of black ink at the photograph.

There was a glass frame so the photograph was not in fact destroyed; yet in one sense the rest of the novel keeps cleaning the glass so that the photograph comes into view with vivid immediacy. That photograph has an enormous effect on many of the characters in My Darling Detective.

You write strong female characters, and the detective in your novel is a woman, which turns noir conventions around (and Jacob seems content to follow Martha's lead).

The act of narrating a story is hardly a passive act, so in this sense, to me Jacob is not passive, but like certain film noir characters, finds himself needing other people--in this case, especially Det. Martha Crauchet--to organize his emotions for him. I worked hard on their relationship. Following her "lead" makes sense, because it is in fact a sequence of forensic leads that Martha follows in order to reveal Jacob's own very complicated past. She directly says to him that she wants to know the man she is marrying. So Martha is a detective in the classic sense, but also because she is solving the mystery of her future husband's life. Jacob comes to knowledge of himself by following his fiancée's leads--fortunate man. He'd be plain stupid not to.

Nova Scotia is central to your literary imagination, particularly Halifax, and the l940s are a time period you revisit. What is compelling about that period for you?

Alistair Macleod said that Halifax combined European sadness with Canadian maritime sadness. For me, Halifax sponsors a kind of displacement of the imagination; I frequently am in Halifax, where I research in the archives, walk the streets, just think about the city while walking through it. I keep notebooks. Then I return to Vermont and write a novel set in Halifax. That is what I mean by displacement of the imagination.

For far too many reasons to relate here, Nova Scotia during World War II is especially compelling. Halifax's immigrant history, wharf, streets, architecture, the coastal fog, the sea--all of it provides, emotionally speaking, literarily speaking, a symphonic sense of the world for me. The novel I am working on now, Ghost First Person, is in fact set in my Vermont farmhouse, but guess what? One character was born in Halifax. --Marilyn Dahl