|

|

| Alejandro Varela Photo: Matias Pelenur | |

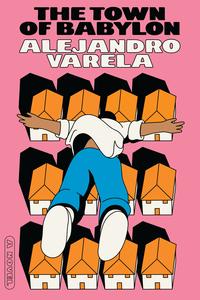

Alejandro Varela is the author of The Town of Babylon, which Astra House will publish in March 2022.

You have a background as a public health researcher. In your writing, from the short story "Carlitos in Charge," as featured in Harper's magazine, to "The People Who Report More Stress'' (from which your forthcoming story collection takes its title), and in this novel, are you following the same interests in your fiction as you did as a researcher?

I have always wanted to make complicated ideas accessible to others. I suspect this has something to do with being a second-generation kid who helped his parents communicate in the dominant language, or being a brown kid in a white neighborhood, or being a gay guy among straight people. If I get them to see that I'm safe, intelligent, American, masculine, etc., they will see how insignificant my differences from them are. But this sort of defensive assimilation was doing myself and my communities a disservice. And yet, that desire to synthesize and communicate effectively remained, and it dovetailed nicely with a career in public health.

Public health work focuses on changing health behaviors, often putting the onus on the individual, but I am more interested in the upstream risk factors, the structural changes that would reduce death and illness across the board—heart disease, cancer, overdose, suicide, occupational deaths, AIDS, etc. Fiction allows me to explore these ideas, in a way that science writing, op-eds, and even creative nonfiction doesn't.

In the acknowledgments in The Town of Babylon, you cite the documentary "The Great Leveller (Paul Sen, 1996), the macaques at Wake Forest, the baboons in the Serengeti, the civil servants at Whitehall, and the residents of Roseto, PA." How did these all influence you?

The Great Leveller is a BBC documentary that was seminal in my understanding of how humans influence one another's health. In brief, hierarchies are deleterious, whether among humans or other primates—baboons and macaques. Animals at the tops of their pyramids are healthier than those at the bottom. The primary mechanism is control: if one feels they have agency over their lives, they are healthier than if they don't. One flaw of hierarchical societies is that if the best health is at the top of the ladder or pyramid, the overwhelming majority of us are destined for poorer health. There are physical costs to being constantly alert or on guard; there's a price to feeling less than or isolated, to not having control over your destiny.

In The Town of Babylon, one character, the Evangelical minister Paul, is a suspect in a long-unsolved murder. Yet, this isn't a work of crime fiction or mystery. Did you struggle to find a balance between the kind of interior, realist mode in which the novel is written and this pulpier more genre element?

In The Town of Babylon, one character, the Evangelical minister Paul, is a suspect in a long-unsolved murder. Yet, this isn't a work of crime fiction or mystery. Did you struggle to find a balance between the kind of interior, realist mode in which the novel is written and this pulpier more genre element?

Life is full of these extraordinary events and moments, and it didn't initially occur to me that I was crossing genres. There are lives and experiences for whom violence of the kind in the book isn't far-fetched or even uncommon. In that regard, maybe I wasn't dipping between genres as much as I was code switching. Or maybe I was falling back on a desire to please everyone at once. I did my best to be mindful of a shifting tone. I didn't want to promise more than I could give, but neither did I want to offer neat resolutions to violence, which, in our society, are typically about retribution and rarely about justice. That sort of conclusion didn't appeal to me, and certainly wouldn't have appealed to Andrés, the narrator.

In The Town of Babylon, one of the characters is Simone, a Black woman whose family experienced racism that couldn't be escaped via upward mobility or assimilation. As an adult, Simone is diagnosed with schizophrenia. Are there parallels between how Simone experiences the world and how her parents experienced it? Is there something you hope readers come away with about the way we treat race and mental illness?

Racism is a very real and persistent risk factor for poor health. Not only does it lead to death directly, as we've seen throughout history and on the nightly news, it especially affects the health of Black and Indigenous people, who have suffered from the lack of access to suitable housing, employment, education, or food; the dispossession of land and culture; and the chronic stress of being treated second-class. While everyone has a degree of predisposition to illness—whether diabetes or schizophrenia—chronic stress and isolation increase the likelihood of illness and poor health outcomes. Meanwhile, Jeremy, whose life was effectively a downward spiral, collects on the generational wealth of his family, as if society had decided long ago that white people would get an unlimited number of opportunities to succeed, while everyone else would be relegated to a two- and three-strikes paradigm. Racism is an affliction for the perpetrator, too. The need to subjugate one's fellow humans is detrimental to the aggressor. The imaginary town in the book, for example, was a stronghold of good health outcomes and strong community until they self-segregated and isolated those who arrived later. In the process, they introduced insecurity, tension, mistrust where it hadn't previously existed. Their health suffered as a result.

Andrés, the narrator and protagonist, stands outside of the community in which he was raised—ultimately a means of self-preservation. He is outraged by this country and its imperial legacy, by the harms wrought by the mechanisms of capitalism, and by the ways in which harmed people have failed to overcome them. But, he finds his way back into the community. Is there something of a solution to our modern condition in the way Andrés connects with the people of his town?

Andrés is the sort of person who wants humanity to thrive, despite having very little tolerance for humans. He finds it difficult to abandon the people he once knew, but he's also wise enough to understand that he cannot change the world one human at a time. He sees the world's problems primarily as structural ones, not interpersonal. Ultimately, his participation in the town is for the sake of his family and for Simone. Anything else is a social experiment for him. He is inclined to push people to reveal themselves. I believe that if Andrés lived in the town, he'd remain guarded, at least at the beginning. Over time, he might get more involved, make strategic moves, and find himself invested. Maybe. For now, the train back to the city is always waiting for him on Sunday afternoons.