Originally from Asheville, N.C., Miranda Richmond Mouillot lives in the South of France with her husband, daughter and cat. In 2004, after graduating from Harvard, she moved to France to uncover the truth about her grandparents' mysterious, decades-long estrangement and piece together the extraordinary story of their experiences during and after World War II. Richmond Mouillot is an independent translator and editor.

Originally from Asheville, N.C., Miranda Richmond Mouillot lives in the South of France with her husband, daughter and cat. In 2004, after graduating from Harvard, she moved to France to uncover the truth about her grandparents' mysterious, decades-long estrangement and piece together the extraordinary story of their experiences during and after World War II. Richmond Mouillot is an independent translator and editor.

In the Author's Note, you describe A Fifty-Year Silence as "a work of memory, not of history." Can you share more about this and how it reflects the book?

A Fifty-Year Silence is not primarily about assembling a definitive, objective account of what happened: it's about remembering what happened and about how remembering affects our lives and the stories we tell. In some ways, I was being literal in calling the book a "work." As I think anyone with trauma or tragedy in his or her family knows, remembering is hard, painful work, with none of the distance that history texts afford. What if we forget? What if we can't forget? Wrestling such memories onto the page is a form of labor for the mind and heart. Of course, once those memories are written down, they become a kind of historical source themselves.

To me, history is a spectrum, or a continuum. On one end is what the French call "history with a capital 'H,'" which draws on many sources to explain the forces that shaped society and determine its present state. At the other end is "history with a lowercase 'h,'" that is, individual people's stories. So framing this book as a work of memory was also a way of orienting it on the "big-H/little-h" spectrum: it's a "little-h" story about two people and their grandchild that points to "big H" questions about the role of memory in our lives, and about how and why we remember.

|

|

| A photo of Miranda's grandparents found in her grandfather's papers after A Fifty-Year Silence was completed, dated July 12, 1944--their wedding day. | |

You worked on A Fifty-Year Silence for 10 years, encountering challenges along the way, including your grandparents' reticence to discuss the past. What kept you going? Why was it important for you to uncover the reason behind their estrangement and to tell their story?

It's impossible to overemphasize the weight and presence of the past in my family and my personal life. As far back as I can remember, I have sensed something lurking that had to be solved, or said, or released. So what kept me going in those first years was my desire to find out what had happened and why it had made my family the way it was.

It's also impossible to overemphasize the weight and presence of my grandparents' personalities. They were terrible, wonderful, utterly unique human beings. When my grandfather began to lose his memory, and I was forced to acknowledge that they would not be around forever, I was overtaken by the desire to capture them in some way, to preserve them for posterity. That desire was a powerful motivation, which grew stronger as the years passed.

In the end, though, it was love. They had endured so much and lost so much; remembering it all was such a heavy burden for them. I wanted them to be able to leave this world with the knowledge that someone would be holding onto their memories. My grandmother read an early version of the book, and it was a gift to see how happy it made her to know something of her life had been written into a story. My grandfather was so senile that I didn't think to show him the book until it was a bound galley, and then only at the urging of a family member. The look on his face when I put it into his hands was the closest thing to a miracle I've ever seen: for a few minutes, the scattered pieces of his mind reassembled. "That's extraordinary," he said, pointing at the photograph of him and my grandmother on the cover. "Who did that?" I knew in that moment that the 10 years had been worth it.

How has your perception of each of your grandparents changed since writing this book and learning more about their lives during and after World War II?

My perception of them hasn't changed so much as deepened. I always thought they were brave, bizarre, tragic, funny and beautiful, and I still do. But I find much more nuance in those adjectives than I did when I started. I guess my conception of their heroism has undergone the most significant change. When I began this project I thought they were heroic mostly for their actions and experiences during and immediately after the war. Now I locate their heroism in how they built their lives in the years and decades that followed. It must have taken every ounce of my grandmother's courage to recognize and accept that my grandfather would never fully resurface from the tragedy of what he had learned at Nuremberg and to move herself and their children away from his whirlpool of sadness and guilt. And I see now how hard my grandfather must have worked to go about his quiet life in Geneva, an effort I couldn't comprehend at the outset.

|

|

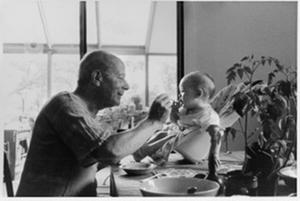

| Armand on one of his rare visits to Asheville, in June 1982 (carefully timed to avoid crossing paths with Anna) | |

A Fifty-Year Silence is centered on your grandparents' experiences, but it's your story as well, including the impact their silence had on your life. In what ways was writing the book transformative for you?

Writing this book laid to rest many of my demons; I no longer have nightmares. There's a reason we employ the phrase "putting it down on paper." A Fifty-Year Silence let me put down the past. I even might go so far as to say that committing the story to paper allowed me to forget. I think that forgetting is one of the biggest, scariest challenges the descendants of trauma survivors must face, and writing, to me, is the best way to confront that fear. I hope this book will help others carrying their own burdens of memory to escape into the forgetfulness that storytelling permits.

What would you most like readers to know about A Fifty-Year Silence?

How much I took out! Making any history into an accessible narrative requires a lot of cutting, and to me, part of the magic of this book is beneath the surface, in the stories it contains but doesn't tell.

|

|

| Anna and Miranda in Pearl River, N.Y., June 1984 | |

Tell us about living in the south of France in a medieval village. What has become of the house your grandparents bought?

In a word, life here is wonderful: we walk everywhere; nearly all our food is grown nearby; and we have a close-knit, supportive community. And of course it's very beautiful. The first landmark my daughter learned to identify from the car was the village's castle, and we eat dinner on a terrace overlooking the ruins of an ancient fort. Our house is built over a small tunnel connecting two narrow stone streets, which means I get to work in a vaulted space that looks a little like a teeny chapel, restored by my husband into a cozy office.

Indisputably, though, village life unfolds in very close quarters. Everyone here knows everyone else (and everyone else's business!), so it's probably not a great place to live if you're trying to hide something. I think for an American the closest comparable experience is life on a college campus but with people of all ages and backgrounds.

As for the house my grandparents bought, it is exactly where I left it, still tangled in issues of inheritance and ownership, none of which has anything to do with me. I do dream of living in it someday, but perhaps I don't need to. Our current house is on the same street, just the right size for our family, and I feel very lucky to be able to live in the place my heart calls home. --Shannon McKenna Schmidt