|

|

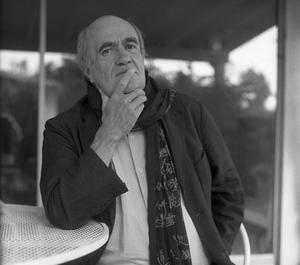

| (photo: Reynaldo Rivera) | |

Colm Tóibín, nominated three times for the Booker Prize (Blackwater Lightship; The Master; The Testament of Mary), is the author of 10 novels, as well as two story collections, and several books of criticism. He was named Laureate for Irish Fiction for 2022-2024 by the Arts Council of Ireland, and is a professor of humanities at Columbia University. He lives in Dublin and New York. Tóibín recently spoke with Shelf Awareness about Long Island (coming from Scribner on May 7, 2024), which continues the story of some of his characters from Brooklyn, the influence of Henry James, his aversion to sequels, and what it's like to return to characters who've been "in my sights" for many years.

You've said that you decided to write Long Island because the right idea--with the right "drama"--struck you at the right time. What was it about this idea that convinced you it was the right time?

It was a simple thing and resembled a flash of lightning. One minute I was walking along the street thinking of nothing much. The next minute I had an idea for the opening of a novel. It struck me almost immediately that the strongest image would have to be at the very opening of the book. The scene that occurred to me had a sort of immediacy and sharp drama that I had never used at the opening of a book before. I thought it was time.

You've also previously expressed that you "hate sequels." Why is that?

A novel depends on the reader's imagination in a way that, say, film does not depend on so much. I write: "She came into the room." The reader has to imagine the room. I don't have to describe it. Nor do I have to describe the "she" each time. In film, you have to give a much more detailed visual sense of the "she" and the "room." You are writing for a reader; you are working out a set of clues and codes by which the reader can see a scene without having everything spelled out. This is the power of fiction, I suppose. If you provide too much information, you snarl the delicate connection between the page and the reader's mind. If you offer too little, then the reader does not have enough nourishment. I see reading as a form of action. The end of a novel is not its end; it is a place where the reader begins to imagine a set of aftermaths. A sequel messes with this delicate process. It says: I didn't tell you enough the last time; here's more. Who wants that?

Was it a challenge to return to these characters after a hiatus? Or did it feel like a homecoming of sorts?

Eilis's mother has changed, or so it seems. And I could work more intensely with the inner life of Jim since I had him on my books, as it were, or in my sights, for so many years. Eilis has become more confident in some ways. It was interesting to work with these three characters whom I have been imagining for years. Also, Nancy in the novel also appears in a long short story, written in the summer of 2001, "The Name of the Game." So, she has been with me for a long time.

The Eilis of Long Island is different from the Eilis of Brooklyn, in no small part because she's decades older. How did you approach a character you knew so well and turn her into someone older, more mature--but still recognizable both to yourself and to readers?

She still keeps a great deal to herself. She is not assertive, but has managed now to control her circumstances more. She is not really social, nor is she introspective. Motherhood has changed her. She puts an enormous amount of care into her children. This is the big change.

Similarly, how did you go about making Eilis's Long Island and Ireland recognizable, both through her eyes and through the broader lens of the '70s?

Mostly, by leaving out public events, events that would not naturally be part of the drama of her life. She refers to Vietnam and to Nixon, but they are small part of a larger picture that is mainly intimate and domestic. She reads the New York Times on Sundays, and this is a very big change in her life. In Ireland, there is one reference to bombs in Dublin. It is there for the reader to notice. And there are a few references to Northern Ireland and the Troubles.

Brooklyn is one of your most beloved stories. Did you, at any point, worry that returning to this story might disrupt or otherwise frustrate the ending you'd already written, the one that fans so appreciated?

Long Island happens 25 years after Brooklyn. The events in Brooklyn are referred to, but there is a new story now, and I make clear in the first three pages that we are in new territory. So I didn't worry about doing damage to the earlier book.

At the beginning of this book, Eilis has a beautiful life--but it's an isolated one, particularly from her Irish roots. Why was that an essential precedent to set for Eilis's journey in Long Island?

Yes, she married Tony and moved into his world. She never developed friendships of her own in America. This made her isolated. I think this happened to anyone who married in another country. For the purposes of the novel, this made a difference. Eilis is alone--no sisters or close pals, no old workmates. This isolation provides for a kind of drama where she is not part of the same society to which her children belong. It means I can work with her interior life with more intensity.

What books did you read while working on Long Island? Do you choose your reading materials based on what you're writing at the moment?

At Columbia University, I was teaching a course on Henry James, on those novels of secrecy and treachery: The Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors, The Wings of a Dove, The Golden Bowl. I am sure that some of that atmosphere, with focus closing in on very few characters who are outside their own country, made its way into the novel.

Your work as an author and thinker far exceeds the task of writing novels. Given the intensity of demand for your talents, how do you choose which jobs to take on, which to leave behind, and when to make time for your own writing?

I do things that interest me. I make time. It's really not a problem. Or maybe I have a way of pretending that it's not! --Lauren Puckett-Pope