A few words on what freedom is.

A few words on what freedom is.

We have this image of how we think it was when the slaves were freed. It is an image of singing and dancing. Of hoes thrown down and hats tossed high. Of leaps and shouts and cries of joy.

But if you read the history, you learn how one-dimensional that image is.

Yes, freedom was joy. It was also outrage for the cruelties they had endured. And worry over what would happen now. And even concern for the occasional benevolent master or mistress now left without slaves to tend them.

And it was love. That's the part we often forget.

When we think of African-American families these days, we are conditioned to think of dysfunction, absence and distance. But history says otherwise. It testifies to the monumental importance the freedmen placed upon family. Freedom, many decided, meant little unless it could fix--and formalize--the connections slavery had torn asunder.

So they wrote letters, they placed ads, they walked thousands of miles, all in the often hopeless hope of restoring--and being restored to--the embrace of family. Can I find my son who was sold from me 20 years ago? Have you seen my sister, who was given away as a wedding gift? Where is the wife whose loss I never ceased to grieve?

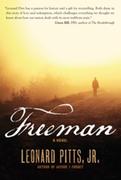

In my novel, Freeman, my protagonist, Sam, embarks on a thousand-mile walk to find Tilda, whom he has not seen in 15 years. He doesn't know where she is. He doesn't know if she is alive. He doesn't know if she's found another man. But he walks anyway. He has no choice. He loves her.

In my novel, Freeman, my protagonist, Sam, embarks on a thousand-mile walk to find Tilda, whom he has not seen in 15 years. He doesn't know where she is. He doesn't know if she is alive. He doesn't know if she's found another man. But he walks anyway. He has no choice. He loves her.

And that embodies the reason I wrote Freeman, the truth I wanted to share with every reader.

Freedom was a love story. --Leonard Pitts, Jr., author of Freeman (Agate Bolden, $16 trade paper)

Listen to an interview with Pitts here.