Duong Thu Huong's The Zenith (see our review below), her sixth novel in English, dismantles the myth of Ho Chi Minh as the saintly founder of an independent Vietnam. Banned from publishing inside Vietnam, Duong Thu Huong first circulated the Vietnamese version of The Zenith on the Internet in January 2009 and instantly caused an uproar among Vietnamese readers both outside and inside the country. Using evidence gathered from 15 years of harrowing research among elite members of the Vietnamese Politburo, Duong Thu Huong's portrayal of Ho Chi Minh is a composite of Lear and Raskolnikov, a man deeply tormented by both false idealism and excessive guilt.

The Zenith is a close collaboration between a dissident author who was a former Party member, an American sympathetic to the South Vietnamese perspective, and his Vietnamese wife--who has experienced both the separation and reunification of Vietnam.

Stephen B. Young co-translated The Zenith with Hoa Pham Young, his wife of 42 years. In 1967, fresh out of Harvard, Young underwent a full-immersion Vietnamese language program in Arlington, Va., to prepare for his subsequent appointment in General Westmoreland's program of economic development and pacification in Vinh Long province, South Vietnam. Hoa Pham Young was born in North Vietnam, but migrated South with her family in 1955. She met her husband in Washington, D.C., where she worked as an interpreter for the U.S. Agency for International Development. They married in 1970 and currently live in St. Paul, Minn., where Hoa Pham Young works as an advocate for the local Asian Pacific communities.

How did you meet author Duong Thu Huong?

Stephen B. Young: We were introduced to her via a mutual Vietnamese friend who lives in California. Then we came to Paris--where she lives--and had dinner with her a few times. This must be around 2008, close to the time when the Vietnamese version of the novel was published. Two years later, at the end of 2010, we undertook the translation project at the suggestion of Huong's literary agent.

How do you collaborate on translation?

How do you collaborate on translation?

Hoa Pham Young: I was the primary translator. I would start first, working nonstop through six to 10 pages, translating mostly for sense, then I would hand over my draft to Steve, who reviewed and considered word choice, flow, effects, etc. When we completed about 50 pages, we would send them to our friend, Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich [who assisted with the editing of the novel's translation], whom we consulted on idioms or arcane references. We also talked frequently on the phone with Huong.

How do you define literary translation? Is it different from other types of translation?

SBY: In literature there is more "soul" at play, more emotions, more colloquial expressions. The goal is not literalism but the creation of a cultural transfer--putting the reader as much as possible into the mind and what is behind that mind--of the author writing in his or her native language. I might say [our] process was like painting in lacquer--laying on one layer after another until the full scene becomes lively and complete.

What were your greatest challenges in translating The Zenith?

HPY: Well, to begin with, we thought the title, The Zenith, wasn't very illustrative, but it was decided that the English title should be close to Au Zenith, its French version. We wanted to translate it as something closer to Duong Thu Huong's original intent, like Blinding Light, to connote the illusion of power, how it looks shiny and bright from afar but in reality brings disappointment and pain, not happiness.

So it's like Plato's myth of the cave, and how one, coming out from the darkness of the cave, should not look directly into the sun?

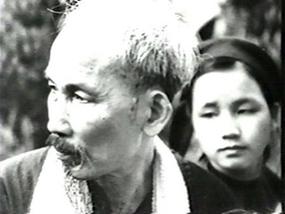

|

| Ho Chi Minh and his young mistress, Nong Thi Xuan. |

SBY: Yes, it's like that. But I think the larger problem has to do with politics, of how the novel will be perceived by different groups of people. This is a novel that shatters the hagiography of Ho Chi Minh. He is not depicted as a saint or a George Washington of the Vietnamese people but as someone who is very passive, very tormented. Duong Thu Huong has said that she based the story on real evidence indicating that Ho Chi Minh had a mistress 40 years his junior who bore him two children. The union was kept secret to preserve Ho's image as "the father of the revolution." His mistress was raped and killed in 1957 by one of his associates when she asked him to acknowledge their relationship publicly. The novel describes how Ho agonizes but does nothing while his lover is brutally murdered and his children taken away from him. You could say that Ho's passivity--as portrayed by Duong Thu Huong--is a kind of complicity that can be linked to all the actions associated with his life in politics, from his slogans of freedom and independence in 1945 to his standing by while his associates killed so many Vietnamese compatriots in the name of the Party and the Nation. At the other end of the spectrum, anti-Communist Vietnamese condemn her novel as being too soft on Ho Chi Minh. They do not see him as a tragic hero bound by the constraints of fate, but as a cold-blooded traitor to his own people. In a way, as translators, we will be in the crossfire, but we felt that it was important to translate the novel, so Americans will have a better understanding of Ho Chi Minh and of Vietnam.

Was, or is, Vietnam, in some fundamental way, also a problem of translation?

SBY: To answer this question would take a book. Some highlights: four historians in particular--Jean Sainteny, Paul Mus, Philip Devilliers and Jean Lacouture--created the story line about the Vietnam War that all Westerners bought into. And it was a lie, an illusion, a failure of translation. That post-World War II story line on Vietnamese communism as nationalism rested upon older French colonial perceptions. It disregarded other viewpoints, that there were other Vietnamese nationalist groups who were not Communist. It also glossed over the fact that Ho Chi Minh and his cohorts received considerable aid from the Chinese and the Soviets. Then the American antiwar movement followed in the French cultural footsteps--imposing a foreign, simplistic construct on the Vietnamese struggle and not listening to what the Vietnamese themselves were saying. --Thuy Dinh, editor, Da Mau magazine