.jpeg)

|

|

| photo: Becki Rutta | |

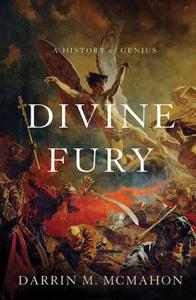

Darrin McMahon is the Ben Weider Professor of History at Florida State University and the author of Enemies of the Enlightenment,on French opposition to the Enlightenment, and Happiness: A History, which explored the many definitions of the idea in different eras. His latest work, Divine Fury: A History of Genius (just published by Basic Books), is a comprehensive history of the many forms "genius" has taken, and sheds light on our modern views of the great intellects.

You write that "the truth is that we live at a time when there is genius in all of us, but very few geniuses to be found." Can you elaborate on this and how we've come to this point?

One of the themes I trace in the book is how the belief in the genius as the highest human type--a creature fundamentally different in kind from all others--was long in tension with a belief in human equality. Both beliefs emerged, paradoxically, in the same general period, the 18th century, when the genius rose to prominence as a new model of human perfection and when people like Thomas Jefferson declared that all human beings were created equal. Yet for a variety of reasons that I describe in the book, it was only after the Second World War that equality began to get the upper hand. We have grown less comfortable investing special individuals with exalted--even godlike--powers. Einstein was the last of the titans to be considered in this way, the genius of geniuses. Since his time, we have democratized and pluralized the concept in keeping with the thought that everyone has a genius for something. So now we face a situation in which a great many are afforded their 15 minutes of genius; we grant to all what was once concentrated in the majestic few. But a world in which all might aspire to genius is a world in which the genius as the exalted exception is dead.

Well, as you know, we definitely have a cult of celebrity today, and it is true that genius and celebrity are frequently spoken of in the same breath in the media and popular culture. Think of Steve Jobs, who was definitely a celebrity and who is often described as a genius.

As your reference to Franklin suggests, the relation between celebrity and genius traces to the 18th century when the cult of genius was born and the word "celebrity" was coined in English and French. Contemporaries remarked on the "privilege of being known by people who don't know you," and Franklin and other geniuses like Jean Jacques Rousseau enjoyed that privilege, while at the same suffering its burdens in the form of prying eyes. Geniuses thereafter were frequently treated as celebrities. But there was something more to the adulation of genius than just the enthusiasm of the star struck. Geniuses were imagined as higher beings and regarded with a kind of veneration and awe that contemporaries themselves liked to a religion. Geniuses, if you like, served as a kind of modern saint.

This religion of genius flourished in the 19th and early 20th centuries and reached its apotheosis in Einstein. But after that, for reasons that I allude to above, the cult of genius fades. We may idolize our celebrity-geniuses today, but we no longer treat them as idols in the way the religion of genius made gods of men.

What lessons have you taken from your research in promoting the stirrings of genius in children?

Really since the time of the genius's emergence as a new human paragon in the 18th century, most commentators have tended to assume that geniuses are born, not made. In other words, that genius is an inherent quality that cannot be learned or acquired. There were, it is true, always dissenters to this opinion, who emphasized that nurture was stronger than nature, and recently psychologists have given that view further credence, stressing the way in which early exposure and training--what my colleague, the psychologist Anders Ericcson, calls "deliberate practice"--gives the lie to the longstanding view that you either have genius or you don't.

That said, I should stress that I am not a psychologist or a specialist on the pedagogy of children. My research doesn't really touch on the question you ask. Personally, I do think that there are good reasons to be skeptical of the view that our aptitude or capacity for high achievement is solely a function of birth. But one thing that I would say based on my study of the history of genius is that parents would be well advised to avoid the term. The label "genius" does more harm than good. --Matthew Tiffany, counselor, writer for Condalmo