_Dough_Menuez.jpeg)

|

|

| photo: Doug Menuez | |

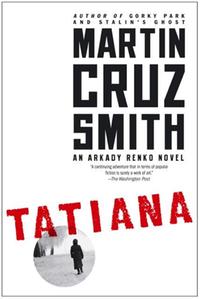

Martin Cruz Smith worked as a journalist, paperback novelist and screenwriter through the 1960s and '70s, before garnering international acclaim with the publication of Gorky Park in 1981, which introduced Russian investigator Arkady Renko. Smith won the Gold Dagger and British Crime Writer's Association Awards for Gorky Park and, among his many honors, has twice won the Dashiell Hammett Award, first for Rose (1996) and then for Havana Bay (1999).

In Tatiana (see our review below), Renko becomes obsessed with the suspicious suicide of Tatiana Petrovna, a daring journalist inspired by real-life martyred reporter Anna Politkovskaya. The story exposes an underworld populated with mobsters, bad poets and outcasts who occupy the "lost city" of Kaliningrad, once the German city of Koenigsburg, in an enclave on the Baltic that Stalin made Russian after World War II. Now, in the post-Soviet era, the city's widespread corruption threatens the top levels of Putin's government.

Smith lives in Marin County, Calif., in a close-knit community where the bestselling author has been known to dress up for Halloween. We talked about his previous books, literary influences, his musician parents and Tatiana at his home, which is decorated with pictures from his many visits to Soviet and post-Soviet Russia.

Many composers and musicians did all kinds of work for hire, much like the kind of writing--from westerns to even a vampire story--you published before Gorky Park.

A friend of mine described it as "industrial strength fiction," which meant pulp fiction. You could establish what your story is very quickly, and you had to have a strong plot and strong character. That's true whether you are doing pulp fiction or Jane Eyre.

In 1981, creating a Russian character in Gorky Park was considered daring, especially by a writer who admittedly knew nothing of Russian culture or literature. What do you think of it now?

I didn't feel I had a choice; it was simply a matter of doing the obvious.

I was sent to do a book about an American detective who shows the Russians how a real cop works. So it was totally out of the blue for everyone. I kept praying that this very obvious idea would not dawn on anyone else--someone better equipped or a better writer or steeped in the Russian culture. So, I just plowed ahead.

Whether a Renko novel or a standalone--like Rose, which is about female miners--your books tend to confront an issue.

I find it makes the writing more interesting to have an issue to write about--whether it be women who work in coal mines or Russian dissidents or Japan's apology for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

It really comes down to looking at things in history and events from another point of view. We are not the be all and end all--there are other points of views that are as valid as ours.

What are some of your literary influences?

What are some of your literary influences?

The Wall Street Journal has a column that asks writers to name five of their favorite books, and I talked about five books I liked a great deal--they were all examples of Russian humor, which is so dark.

One is called Mastering the Art of Soviet Cuisine by Anya Von Bremzen--it is quite a good book, period, as a memoir, but it has these touches that are purely Russian, like how to drink vodka by pinching your nose so that you don't get any oxygen mixed in with the spirits. I thought, this was done as advice with the full expectation that you would be drinking vodka.

Tell us how the life and murder of Anna Politkovskaya inspired Tatiana.

I was very much taken with her story and her end and how everyone expected her to be martyred. I certainly would not have written the book without her in my mind's eye all the time, because she was astonishingly brave and very human.

About the same time I was getting interested in Anna Politkovskaya, I became aware that there was this enclave--Kaliningrad--a separate piece of Russia apart from Russia that was pinched against the sea by Lithuania and Poland.

And then I came upon this other complication that I liked, which was the history of amber and the role amber played in the history of Kaliningrad. I had no idea that 95% of all the amber in the world comes from this one little place.

And then I have always been interested in Russian poetry, so I thought it would be nice to have a poet in there--not a very good one, but a poet.

And then I thought I'd add the complication of the time bomb in Arkady's head, which has been there for a couple of books.

Those who are up on Renko know that the biological father of Zhenya, Renko's surrogate chess-hustler teenage son, shot the investigator in the head and that the bullet is lodged dangerously in his brain. Now that you have been diagnosed with Parkinson's, does that change the way you write about Renko?

It changes your attitude toward the passage of time, because you feel there is a little bit of a time limit on yourself.

I didn't go public with it [Parkinson's], because there are plenty of people in the world who have worse and they are all around. It's sort of like handing people a bag that's heavy and full and you can't see what's in it. People don't know what to do with it. They say, now that I know Smith has Parkinson's, does that mean anything for me?

What has it meant to you in terms of your writing?

I have the most incredible support system in the world. I've got Em, who is willing to write what I dictate.

Em is Emily, your college sweetheart who became your wife. Have your dictated to her before?

It started with this book and it's very different. First, it takes incredible patience on Em's part. And it takes some patience on my part. If I don't think of anything for five minutes, you have no idea how long five minutes can be. So, I dictate and she types. You do what you have no choice avoiding.

If you were going to start out today, what kind of writing would you do?

I think I chanced on a genre that was reaching its peak--this literary thriller. I'd rather not begin again; I'd rather have parallel careers--like John Banville. I really have to admire how well he writes and doesn't lower his standards.

Tell us about your Halloween costume this year.

I had about two seconds to come up with a costume--so I put on my bathrobe and slippers. I was a "writer." But. If you were really up to seeing it, I was Kingsley Amis, whom I identify with not only as the writer of Lucky Jim, but also Everyday Drinking--just the title alone goes along with Mastering the Art of Soviet Cuisine.

What's next?

A stand-alone. I think Venice, but I don't want to say too much. When you're excited about something, it's very easy to start talking about it and you can talk yourself right out of a book. --Bridget Kinsella