|

|

| photo: Melanie Dunea | |

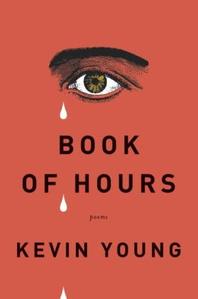

Kevin Young is the author of eight books of poetry and editor of eight others. His collection Ardency: A Chronicle of the Amistad Rebels won the 2012 American Book Award. The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness won the Graywolf Nonfiction Prize, was a New York Times Notable Book for 2012, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism, and winner of the PEN Open Award. He is Atticus Haygood Professor of Creative Writing and English and curator of literary collections and the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library at Emory University in Atlanta. Young's new book of poems, Book of Hours (our review is below), is an accessible, musical meditation on death, birth and the blues life can bring.

What early experiences drew you into poetry and the written word?

Looking back, there was a summer class I took and that's when I started writing. It was pretty early--I was 13 or 14. Before that I'd written little stories, but in this class we wrote poems, and that was just amazing for me. I started reading and writing what I could. I was living in Kansas so the bookstore lacked a lot of poetry. In a way, that was good because I picked up whatever was there and it gave me a broad view of poetry, then an eclectic one.

The poems in the Book of Hours have many themes, but the themes that pop out are death and grief and birth and joy. When did it become clear to you that the poems you were writing at the time would move in this direction?

I wish I had a dated time. I don't remember not writing them in the sense that after my father died, [I just wrote] for survival. You're not really trying to get some perfect thing down or even a poem. I didn't feel like writing at all. I certainly didn't feel like writing poems. Later I wrote the poems that were the odes of death and rebirth, poems about food. It was a way of talking about him and the hunger for larger things--odes to greens, odes to crawfish--all the foods from Louisiana where my parents are from and what I grew up eating. Then I returned to these moments and tried to capture what it was like in those days, weeks and years after he died. I don't know if I thought of writing a book of him, but I certainly wanted to get some of that stuff down. I find meaning in it. I think people do after grief.

Some of your past collections--To Repel Ghosts, for example--riff on your cultural heroes and almost speak through them. With Book of Hours, are we getting Kevin Young unplugged? Everything seems direct in your recent poems.

I think that as far as poems go, I specifically didn't want there to be an "I." I wanted it to be a "we" or "you," anything other than "I." I was writing about Basquiat, who I didn't know, but I seemed to know through his paintings. This is sort of inside out: I wanted there to be an "I," but I hope there is a "we" in the sense that we go through grief in different ways, at different times. I wanted that to resonate with people. I've been really honored to have people come up to me and say that's what happened as they read the book.

Well, blues are a kind of map. They're a way of looking at the world and a record about it, that way of laughing that keeps you from crying. They're a way of trying to name a thing in order to get past it, as opposed to many other forms which are about glossing over it. It is really about going to the heart of the thing--not side-stepping it, but stepping through it and coming out on the other side.

There is a wonderful series of poems in the book addressed to your wife and child. What was it like to write these? I see some joy, but also some apprehension.

I think they came along the way. I was writing them as a kind of necessity. When your life changes, you want to write about it. I didn't know if they would ever become poems, but they seemed to, more and more. I love the language of pregnancy. It's like a whole other world. That was also part of the investigation of these poems--the pleasure of it, at least.

Later in the collection, in the poem "Pieta," you write, "I hunted heaven for him/ no dice." Are you talking about your father and his passing? How much of this poem is you shaking your fist at heaven, or are you just learning to accept?

That is a good question! I would leave it to readers to feel that out. I don't know if I totally know. I still feel so close to the poems. I think I was trying to understand the afterlife of grief, not just afterlife in the big sense. What does it mean a year or 10 years later, which it is now. There is a poem, for instance, about getting my eyes checked when no one in my life had ever done that. That's a crazy strange feeling, and the eyes become symbolic and that courses through the book. I was trying to wrestle with those facts and that questioning. Doubt is a part of faith. I also think the poems are interested in seeing everydayness as a kind of faith, and also memory, as in being faithful to someone's memory. There's a lot swirling around in there.

The last section of the Book of Hours seems like the place where you pull together the strands--the grief about your dad's death and the birth of your child. The language in that section is more simple and direct. How do you see that in relation to the rest of the poems?

I really wanted that last part to be resonant and musical--simple in the best sense, like a choir. I think pure and beautiful and clear are the sounds I wanted, natural and high, like reaching for a high note. They're kind of pastoral, which is kind of a natural balm which happens in grief.

I wanted them to have structure, and I thought a lot about an actual Book of Hours, which traditionally has hours of the day for prayer, so things are evening or morning. There is a lot of language that comes from the spiritual; the valley and the river, really large landscapes, meaningful places, some of the music I love and some of the feelings with wresting with grief. I wanted the voice to be muscular and something that wasn't talking about autobiography, but about self in the bigger sense.

There is a musicality to your voice. Sometimes people take poetry as this overly innate thing, but yours is blues-based. How do you develop that music to the line while keeping it simple?

If I knew, I'd try to do it more! I thought a lot about the line as a kind of music, and I really hope that came to fruition in this book. [I was] trying to create a song for the dead, but also for the future. What's great about music is that it's time-bound and also timeless. You hear a song you love and remember the moment you first heard it. Then, you hear it again. Poems do that, and they can do that over a longer period of time. I love that there are poems I read when I was 20 and that I liked but didn't know why, but now I know exactly why. We move through life and see different things at different moments, and that's the book I wanted to write. --Donald Powell, freelance writer