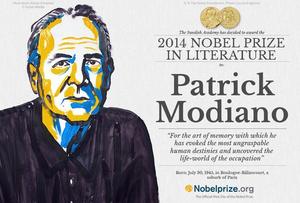

Patrick Modiano, winner of the 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature, is virtually unknown in the United States, although he wrote the screenplay for one of the classic French films of the '70s, Louis Malle's controversial Lacombe, Lucien, about a 17-year-old peasant boy in Nazi-occupied France who joins a group of Fascist collaborators, until he falls in love with a Jewish girl.

Patrick Modiano, winner of the 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature, is virtually unknown in the United States, although he wrote the screenplay for one of the classic French films of the '70s, Louis Malle's controversial Lacombe, Lucien, about a 17-year-old peasant boy in Nazi-occupied France who joins a group of Fascist collaborators, until he falls in love with a Jewish girl.

Like fellow Frenchman Marcel Proust, Modiano's concerns are time and memory. Unlike Proust, he writes very short novels in clear, simple prose. Most of his melancholy stories take place in the past, and consist of patched-together pieces of memory. The 2014 Nobel Prize cited Modiano "for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation."

One character after another in his fiction reveals a piece of a puzzle, though not always the piece you think it will be. Clerks and service personnel frequently provide clues, along with porters and concierges, removal men and waiters, hotel managers and nightclub bartenders, black marketeers and housekeepers. Characters recur from one novel to the next: Modiano's father, Albert, mysteriously released from jail; the love of his youth, Jacqueline; a caring and protective older woman, variously named; and the deadly, metamorphosing, self-reinventing Pacheco. Though they may not know themselves very well, Modiano's characters know every street in Paris, and name whichever one they are wandering down in the fog of memory. Layer by layer, Modiano peels back one memory to reveal another beneath it.

His works consist of almost 30 short novels, his form of choice, of which only half a dozen are currently in English translation (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt will publish Modiano's latest novel, Pour que tu ne te perdes pas dans le quartier, or So You Don't Get Lost in the Neighborhood, in fall 2015). Among those now available:

Modiano's 1978 novel Rue des Boutiques Obscures (literally Street of Dark Shops), translated as Missing Person, was awarded France's highest literary prize, the Prix Goncourt. Private investigator Guy Roland finds himself out of a job after eight years in detection, and decides to turn his skills upon himself. A survivor of the Nazi occupation of France, his past has inexplicably been erased by amnesia, leaving him searching for clues to his own identity. Two bartenders remember vaguely that he used to go around with a tall Russian, which starts him on a journey through Russian émigrés, yellowing photos, newspaper clippings, phone directories, old documents, memorabilia and dusty boxes of souvenirs. The villain is memory. Do we really remember who we are? How much of the past remains accessible to us?

Modiano's 1990 novel Voyages de noces, translated as Honeymoon, follows a documentary filmmaker about to escape from his unfaithful wife and unsatisfying career by disappearing on a supposed flight to Brazil. Jean B. slips out of his own life and vanishes, returning to Paris like a ghost to secretly walk through the rooms of his former home. Changing hotels every week, he arrives at one shortly after a woman has committed suicide there, a woman he once knew. He begins writing about her, re-creating his experience with Ingrid 18 years earlier when he was picked up hitchhiking by her and Rigaud, her new husband. Swept away by the two charming illegal drifters, Jean B. embarked on a stolen holiday during wartime, in a world where guests had false papers and lived in fear of police raids. Soon Jean is telling the story from Rigaud's point of view, reconstructing their lives before they met him, trying to understand what drove Ingrid to take her own life.

The first short novel in Polizzotti's excellent translation is from 1993--Chien de printemps (literally Dog of Spring, or Goddamn Spring), here translated as Afterimage. It's a mosaic of memory fragments from the author's friendship with the photographer Francis Jansen, dating from when Jansen used Modiano and his girlfriend as his models for an article on Paris youth. The 19-year-old narrator offers to catalogue all of Jansen's photos. The two become friends. Nicknaming him Scribe, antisocial Jansen mentors him in the realities of life, including dealing with a romantically obsessed married woman and her jealous husband. Famed for his photos of fences, walls, stairs, garages, and his own shoes, after taking pictures for nearly 25 years, Jansen gives his camera to his young Scribe.

The title novella in the collection, Suspended Sentences (Remise de peine, 1988), takes place during wartime in a small town just outside Paris. An actress in a touring company leaves her two sons with colorful, eccentric friends for more than a year while she's on the road. Ten-year-old narrator Patouche, nicknamed "blissful idiot," is expelled from school while staying in the house with Little Helene, a tiny former circus acrobat, and beautiful 26-year-old Annie, who wears a man's leather jacket. Patouche and his brother soon discover the house has secrets. Annie's friends have taken political risks, and an impending police raid will force her to move the boys into the house across the street before it's too late.

The collection concludes with Flowers of Ruin (Fleurs de ruine, 1991), which investigates a happily married young couple who in 1933 take their own lives for no apparent reason. They are last seen at nightclubs with two other couples. Twenty-five years later, the narrator tries to find answers and becomes obsessed unearthing of the identity of a man who may have crossed their path that fateful night, the mysterious Pacheco, pretending to live where he doesn't live, flinching at the mention of earlier times, wanted by the law for colluding with the enemy. Pacheco leaves his suitcase behind and never returns. Locked inside that suitcase is a clue to the fate of the doomed couple.

Out of the Dark is a translation of Modiano's 1996 novel Du plus loin de l'oubli (literally, From the Far Edge of Forgetfulness). The narrator recalls 30 years ago, when he was an underage drifter with a false student ID card who survived by selling used art books and knew every apartment building in Paris with two exits. He meets Gerald Van Bever, who lives for the casinos on weekends, and becomes spellbound by Gerald's wife, Jacqueline, who begs him to steal a suitcase from a dentist's office. In classic noir fashion, the smitten young man commits the crime. That's where the similarity with noir ends. The party sequence finale, in which he's an uninvited guest posing as the friend of a friend in his obsessive search for his lost love is a suspense masterpiece.

Modiano's novels are so short you can read them easily in one sitting, but their brevity doesn't prevent them from bursting out of the restrictions of detective fiction and morphing beyond genre recognition. Modiano has put his finger on something quite creepy, the fluid drift and metamorphosis of personality through time, how we become strangers to our past selves, only to become detectives in search of our own identities, perpetually trying to solve the mystery of who we really are. --Nick DiMartino, Nick's Picks, University Book Store, Seattle, Wash.