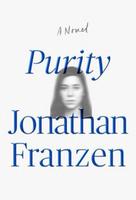

Jonathan Franzen is a divisive figure. To some, he's a genius--a Great American Novelist, even. To others, he represents the ultimate embodiment of the privileged white male author. In his newest novel, Purity, Franzen has out-Franzened himself with a massive (576 pages), flawed, ambitious and frequently revelatory work of art. On its surface, Purity represents Franzen doubling down. Instead of a Great American Novel, it aims to be a Great Global Novel, with events bouncing from East Germany in the 1980s to Oakland in the present day and Bolivia in the recent past, to name a few of the diverse settings. While Franzen's cast of characters still lacks racial diversity, Freedom feels cramped and monochromatic by comparison.

Franzen could have crafted a good novel simply by marrying this new, broader canvas to his considerable skill as a prose stylist, but what sets Purity apart is something surprising: empathy. Previous Franzen novels at times feel weighed down by irony, too focused on wryly pointing out the flaws of their protagonists to make the reader care for them. Purity is just the opposite. Its guilt-ridden misfits are extended authorial forgiveness and love for even their worst crimes. In Purity, Franzen's true achievement is trading cynicism for compassion. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books