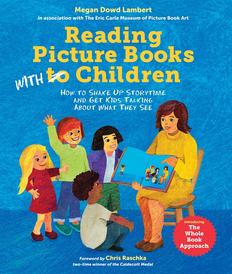

Megan Dowd Lambert is an author, reviewer and professor of Children's Literature at Simmons College. Her book, Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking About What They See (Charlesbridge), developed in association with the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, is a practical guide for caretakers on how to read picture books with children. She lives with her husband and seven children in western Massachusetts.

Megan Dowd Lambert is an author, reviewer and professor of Children's Literature at Simmons College. Her book, Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking About What They See (Charlesbridge), developed in association with the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, is a practical guide for caretakers on how to read picture books with children. She lives with her husband and seven children in western Massachusetts.

Reading Picture Books with Children introduces the Whole Book Approach, a story time model I developed in association with the Carle Museum that aims to engage children with the picture book as a visual art form. I don't think of the Whole Book Approach as the best or only way to lead story time; instead, I present it as an approach to shared reading that centers children's ideas and questions while fostering critical thinking about how picture book text, design and illustration combine to tell stories and convey information.

There are different story time approaches that all have different goals, and adults should consider this when thinking about how they share picture books with children--whether at home, in libraries or classrooms, or elsewhere. The Whole Book Approach is a means of reading with children, as opposed to reading to children; it has the adult lead story time not as a storyteller giving a performance, but as the conduit through which children receive picture books and as the facilitator of discussions that emerge from that reception.

This means I center children's ideas and questions so that their voices become as important in the shared reading as the text is, and their interpretations take precedence over my own. I don't ask them to wait until the end of the book to speak. I don't steer conversation toward an acceptance of a theme or interpretation that I've predetermined. Instead, I ask open-ended questions (many inspired by Visual Thinking Strategies and Dialogic Reading techniques) to prompt children to read pictures and reflect on design. I welcome spontaneous responses, too. I also often ask children to engage in metacognition--to think about their thinking and provide evidence to support their ideas. This is a cornerstone of critical thinking, since it's one thing to say what you think and quite another to say why you think what you do. How do I do this? I use the picture book as a whole--its text, art and design elements like the jacket, endpapers, front matter and layout choices--to prompt children's responses and to ground their spontaneous remarks. And, yes, I do incorporate the above book terminology into story time. If three-year-olds can name dozens of dinosaurs, why not provide them with vocabulary like endpapers or gutter and instill a sense of entitlement to, and appreciation of, the physical book? This seems especially important in the digital age, since many picture book design elements don't translate well, or at all, onto e-platforms.

How do I do this? I use the picture book as a whole--its text, art and design elements like the jacket, endpapers, front matter and layout choices--to prompt children's responses and to ground their spontaneous remarks. And, yes, I do incorporate the above book terminology into story time. If three-year-olds can name dozens of dinosaurs, why not provide them with vocabulary like endpapers or gutter and instill a sense of entitlement to, and appreciation of, the physical book? This seems especially important in the digital age, since many picture book design elements don't translate well, or at all, onto e-platforms.

"Endpapers give us clues," I might say. "What do you see happening on these endpapers that could be a clue about the story we're going to read?"

Or I might hold up two picture books and ask kids to consider why one has a portrait (vertical) layout and one a landscape (horizontal) layout. Once I did just this at the Carle with Ludwig Bemelmans's Madeline and Eric Carle's The Very Hungry Caterpillar, and a child exclaimed, "That book [Madeline] is so tall because of the... heightful tower!"

I developed the Whole Book Approach as a way of getting kids to talk about art and design, but by making it clear that their thoughts and ideas were important to me, things that were important to them started bubbling to the surface during our discussions. In my experience, children usually first comment on characters, rather than setting elements like the "heightful" Eiffel Tower that dominates Madeline's jacket art. And, time and again, I've found that what might be regarded as the democratizing impact of the Whole Book Approach, or the shifting of power from the adult reader to child readers, can empower them to critically engage with picture book characterization.

When this happens, the Whole Book Approach's focus on art and design can give way to, or become entwined with, ideological discussions about representations of race, gender, class and other aspects of identity. I've led story times in which kids have interrogated what they saw as a false racial opposition between characters in Chris Raschka's Yo! Yes?; examined class inequities and gender dynamics at play in Molly Bang's wordless picture book The Grey Lady and the Strawberry Snatcher; embraced Bryan Collier's work with visual metaphors to illuminate the struggle against racism in Doreen Rappaport's Martin's Big Words: The Life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; and applauded the depiction of a nurturing, black father-figure in Adam Rex and Christian Robinson's School's First Day of School. Each of these instances, and many more, have reinforced my conviction that we do a disservice to children and to ourselves when we underestimate their capacity to engage in critical conversations.

No matter what story time discussions end up addressing, the key to all this Whole Book Approach work is to keep it child-centered and engaging, even playful. I never want story time to feel like a test, nor to allow inquiry into art, design and text to undermine reading pleasure. But, I reject the notion that critical thinking opposes or eliminates enjoyment. Perhaps story time-as-book-discussion (reading with children) offers a different kind of pleasure than does story time-as-performance (reading to children). But when kids have "aha" moments, or when they boldly read against texts, or when they listen to others' responses and get to know a book they love a little better, the delight they experience is just as real as the pleasure of getting blissfully lost in story. There's room for both kinds of reading experiences at story time, as surely as there's room for the picture book as an art form to not only survive, but thrive, in the digital age. --Megan Dowd Lambert