_Nina_Subin.jpg)

|

|

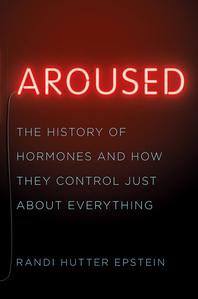

| photo: Nina Subin | |

Your book touches on so many aspects of human life--our health, our happiness, our gender and sexuality. What surprised you the most during your research?

We think of endocrinology as a field that got going at the end of the 1800s. The word "hormone" was coined in 1905. And yet it really began in 1848--not in a famous research center--but in a small village in Germany, in Dr. Arnold Berthold's backyard. Berthold did some weird experiments with his chickens: castrating them and switching testicles. He even put a testicle into the belly (the belly!) of a castrated rooster and watched the rooster become re-energized, chasing the hens. Before Berthold, there was no recognition that hormones--and the glands that spew them--could work from just anywhere in the body, that somehow these chemicals would find their targets. Berthold didn't promote his ideas, so they were hidden for another half century. Then other researchers found his ideas, did more research and voila! The field blossomed.

I loved your chapter on the American neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing. We learn, among many things, that his brain collection is housed in the basement of one of Yale's medical student dorms. How is it that a research collection by one of the most renowned doctors of the 20th century has been all but completely forgotten?

You have to remember that until a student and neurosurgeon repaired the specimens, they weren't recognized as a research collection but were simply seen more as detritus--they were old jars, many with puckered, dried-out weird bits of brains. Most folks didn't know they were the collection of a pioneering neurosurgeon. When I was a student in the medical school in the 1980s, we had no clue about the brains. This shows you that discovery takes not only the finding of a treasure but having the scientific and historical knowledge to recognize its impact.

What is it like making the trip down those stairs to see the collection firsthand?

It's one of my favorite class trips. Yes, spooky, but in an exciting sort of way. The restored brains that are in the library--along with Cushing memorabilia and his collection of medical art--is really quite beautiful. Even my husband, who is not one for enjoying jarred brains, was fascinated. I've also taken students to the basement where there are still unrestored brains. I can appreciate that it's super-creepy and may not be everyone's idea of a fun outing, but my students (many of whom are science majors) seemed to enjoy it.

In your chapter on gender hormones, you mention Christine Jorgensen. You call her the "Caitlyn Jenner of the 1950s." Who was she, and how does her story fit into the history of the transgender community?

In your chapter on gender hormones, you mention Christine Jorgensen. You call her the "Caitlyn Jenner of the 1950s." Who was she, and how does her story fit into the history of the transgender community?Christine Jorgensen was born George Jorgensen. After a stint in the army during World War II, Jorgensen began to question the gender of birth. Transgender was not a term then. There were no support groups, no one to turn to. But Jorgensen had heard about testosterone as the male hormone and estrogen as the female one, so he convinced a pharmacist to give him estrogen and he started taking it.

Then he heard about a surgeon in Europe performing sex-changing surgery and made his way across the ocean, shortly after becoming Christine Jorgensen. I compare Jorgensen with Jenner because, while there were other people back then who felt they were born into the wrong body, most of them did not want to publicize the way they felt. Jorgensen made headlines and became proud of her newfound status. She wrote a memoir and became a nightclub singer--admitting that she had no talent but she loved performing and showing her new self.

One of the more surprising revelations in this book is that the greater scientific community still knows so little about how our hormones shape and control who we are. Why don't we know more? What obstacles are doctors and scientists up against in this area of research?

It isn't that doctors are against obstacles, at least not in the sense that anyone is preventing them from doing research. It's more that we are learning that hormones are complex and influence each other and our immune system. Also, one person's body may be more sensitive to a hormone or have more hormone receptors--so it's not just about levels but the way each body reacts with hormones. And making this even more complicated is the fact that we can't make a direct line from what we see in animals to what's going on in humans. What is the role of hormones and gender? We can't study that in animals because we're not sure dogs or cats or other lab animals have a sense of gender. We can watch mating behavior, but that's very different from gender identity. That said, I think we are in a very exciting time as scientists delve deeper in the understanding of our inner chemistry.

Where do you, as a doctor, see hormone research going in the next decade?

With new imaging techniques and genetic analysis--and interdisciplinary work--we are on the verge of many advances in endocrinology. I think the next discoveries will be in the connections between our immune system, our neurotransmitters and our hormones. --Amy Brady, freelance writer and editor