|

|

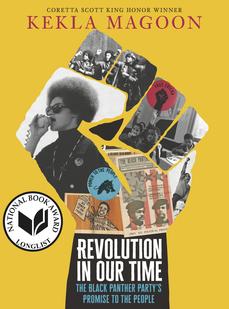

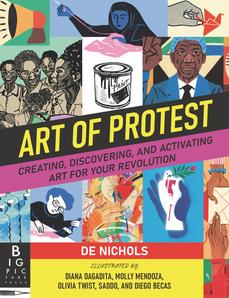

We asked YA authors Kekla Magoon and De Nichols to talk about their recently published books, Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party's Promise to the People (Candlewick Press) and Art of Protest: Creating, Discovering, and Activating Art for Your Revolution (Big Picture Press) and how they see protest and social activism.

Kekla Magoon's novel The Rock and the River won the Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe New Talent Author Award. She is the Margaret A. Edwards Award-winning author of more than a dozen books for young readers and is the coauthor, with Ilyasah Shabazz, of X: A Novel, which was long-listed for the National Book Award and received an NAACP Image Award and a Coretta Scott King Honor. Magoon grew up in Indiana and now lives in Vermont, where she serves on the faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

De Nichols is an arts-based organizer, social impact designer, serial entrepreneur and lecturer who mobilizes change-makers nationwide to develop creative approaches to social, civic and racial justice issues. She is currently a senior user experience researcher of product inclusion at YouTube and a 2020 Loeb Fellow at Harvard University's Graduate School of Design.

Kekla Magoon: What drew you to the art of protest, in particular? Your book is exciting, much like the art it is documenting.

De Nichols: In 2014, my community in St. Louis was directly confronted with the ills of police brutality when Michael Brown was murdered in the streets of Ferguson. During that time, as the city took to the streets in protest, I showed up with art. My friends and I co-created signs, sculptures, performances and other forms of protest art for more than 400 days during that time. Art of Protest shares a bit of that story but also connects a longer lineage of protest art from across the globe.

|

|

| Kekla Magoon (photo: Alice Dodge) | |

Magoon: I love that. It's funny, we were asked to talk about "what is protest?" and it strikes me that it can be anything. ANYTHING.

Nichols: ANYTHING! And everything.

Magoon: People have used words and every kind of imaginable visual art to protest; they've used their own bodies to protest.

Nichols: Right on. I'm curious about how the visual and creative nature of protest shows up in your book and the stories of the Black Panthers. There's so much there: the logos, the fashion, the creations of designers like Emory Douglas.

Magoon: Absolutely. Certain symbols still evoke the Panthers, over 50 years later: black leather jackets, berets, the panther logo, the raised Black fist. The Panthers were aware of what imagery and art could add to the movement. They published a weekly newspaper featuring art and writing by members, including the powerful and distinctive art by Minister of Culture Emory Douglas.

|

|

| De Nichols | |

Nichols: I'm moved by this. I lead the studio practice for the national Design as Protest collective. We got the chance to speak with Black Panther leader David Hilliard about the creative foundations and power of the newspaper. And as grassroots media has evolved, we asked him what the future of movement storytelling looks like.

Magoon: Wow. The question of movement storytelling resonates with me. With Revolution in Our Time, I weighed a feeling of obligation to tell the story of the Panthers the way it has been told by Panther leaders with a desire to tell the story in a way that would make the narrative feel relevant to today's young activists. I wrote about the tension between elder and younger generations of activists, and how both tend to discount aspects of the other's experience and viewpoint. The future I want for movement storytelling is to bridge those gaps, so we can learn from past activist generations while taking what we need to build our own, forward-looking movement that speaks to our time and our needs.

Nichols: In order to control the narrative and shift it toward progress, we must own our stories. With social media, that means unearthing more of our truths by building and leveraging platforms. There is great social currency and power in using it as a tool that builds on the foundations of the work of the Panthers.

Magoon: How do you think visual art can be used on social media better?

Nichols: The virality of imagery is an area of opportunity. In recent years, gaslighting and retraumatization have unfolded from constantly witnessing Black death and pain online. Creating, seeing, and sharing protest art online reignites the soul. It equips us and our movements with counter-imagery to respond to injustices in ways that connect us and remind us of our humanity and dignity.

Magoon: Creating the counter-image is important to me. One of the strongest images that evokes the Panthers is Black men in uniform with large rifles. My goal with Revolution in Our Time was to get behind that "snapshot" to tell a deeper, broader story. The Panthers were not advocates of violence--they were community organizers with the goal of fundamentally transforming the structures of society through a revolution of ideas and practices, through caring for the people and inspiring others to do the same.

Nichols: Exactly.

Magoon: The Panthers wanted that snapshot associated with them, to underscore the value of self-defense and power, but history has turned it against them. Art is expansive, but symbols have the potential to be reductive. Do you think artists directly contend with this idea as a challenge, and/or use it to their advantage?

Nichols: Artists have to contend with both the harm and power of images. For protest, there is greater power in honoring and illustrating multiplicity--in making sure that we are not replicating monolithic views of who any of our communities are. Reduction and generalization are core strategies of white supremacist culture. These methods strip away the complexity and beauty of people's humanity so that harm and injustice might be justified.

Magoon: True. The nuance and the need to hold multiple ideas and impressions at once is one of the challenges of communicating with people who want to be allies but are struggling to break out of simplistic thinking.

Nichols: What is the solution? Is there a piece of advice that you would give to others looking to raise awareness for a social cause, but perhaps struggling?

Magoon: I want there to be a singular piece of advice, but it's hard to have only one thing work when we're trying to transform deeply systemic problems. My best advice is to be open-minded, flexible and willing to beat the same drum until the rhythm is heard everywhere.

Nichols: I would add that there is value in listening to those who have been targeted by systemic ills. As we stand on the shoulders of the work of organizers like the Black Panthers, there is so much that we gain from their experiences and their struggles. Our books are both catalysts and starting points. There's a lot that readers can take from them and then continue to explore. So that's my encouragement: learn from those around you (and before you), and don't be afraid to explore and create.