|

|

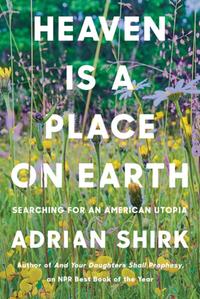

| photo: Eleanor Howe | |

Adrian Shirk is the author of And Your Daughters Shall Prophesy, a study of American female mystics and prophets, named an NPR Best Book of 2017. Her second work of nonfiction, Heaven Is a Place on Earth (Counterpoint, $26; reviewed in this issue), is an exploration of American utopian experiments, from the Shakers to the radical faerie communes of Short Mountain to the Bronx rebuilding movement. She teaches in Pratt Institute's BFA Creative Writing Program and lives at the Mutual Aid Society in the Catskill mountains.

Throughout the book, you wrestle with the contradiction that nowhere perfect exists, yet people keep trying to create ideal communities. Is the attempt the important thing?

Perfection is only the dream from which the utopian attempt issues. Utopianism is about enacting immediate change, rather than reform--some kind of direct action that interrupts the life required by a violent empire. A noble failure is the greatest achievement, perhaps, given that longevity often leads to the accumulation of wealth and power in a way that will ultimately corrupt what might have been prophetic or paradigm-shifting about the utopian experiment to begin with.

And the utopian "escape" can and has often been paired with engagement with the world's problems--in fact, utopianism really is an engagement with the world in a deep way; the very impulse to dream of a utopian alternative is a direct response to the conditions of an unjust empire. There would be no need to "escape" otherwise, or architect alternatives.

At one point you say, "utopia is never far from its opposite." Dystopian novels are as popular as ever. To what extent do you think real-life utopias and fictional dystopias have the same aims?

I think real-life utopian experiments and fictional dystopias both offer warnings about the dangers of relying too much on ideology, and not enough on living, or choosing the person over the belief. So, in that way, real utopian experiments and fictional dystopian narratives are two sides of the same coin: a dystopia is a utopia that lost sight of--or never included--understanding itself as resistance to a violent empire, and thus starts to look like a violent empire itself.

Where you grew up in Oregon, the population is nearly three-quarters white, a legacy of Black exclusion policies from the 1850s onward. What are your concerns about the class and homogeneity implications of utopian experiments?

Oregon came into focus for me because of the way that the 19th-century white settlers there explicitly articulated a plan to create an all-white paradise. They really believed that it was a benevolent and public good, and that their lack of participation in chattel slavery and the Civil War was evidence of their good intentions. So that's perhaps among the worst-case scenarios.

If the pursuit of utopia is in some way about a rejection of the terms you've been asked to live under in your particular society or culture, and the innovation of an immediate alternative, then we quickly find ourselves asking: Who among us has the time, space, energy, money and access to engage in the risk of such an alternative? Even if said "utopian experiment" isn't some pastoral exit to a rural commune but perhaps, simply, the local volunteer-run women's shelter they want to contribute to or the food co-op they'd like to join in exchange for a weekly work shift.

And I guess that's why it was important to me to really broaden the scope of "utopia" as a descriptive category in the book: Where do we see evidence of utopian activity in our immediate surroundings, and how can we orient ourselves toward it, if we want to? Over time, I became more curious about communities or movements that perhaps hadn't achieved some perfect stasis or solution, but who had, as a primary tenet of their project, centered and maintained active concerns about homogeneity.

Intentional communities can be more environmentally sustainable because of the back-to-the-land philosophy and efforts at food and energy self-sufficiency. Can you imagine this model becoming more popular as we move away from fossil fuels?

Intentional communities can be more environmentally sustainable because of the back-to-the-land philosophy and efforts at food and energy self-sufficiency. Can you imagine this model becoming more popular as we move away from fossil fuels?

Absolutely--and it already is. The Foundation of Intentional Communities reported in 2019 that, in the last decade, the United States alone has seen an increase of approximately 100,000 people who have moved into cooperative living arrangements, largely for reasons to do with ecological sustainability, as well as financial and material sustainability. That's distinct from, say, the mid-20th-century surge in communal living that was more shaped by ideological and political motives. There's something particular about communitarian upticks in moments of material emergency.

A few years ago, with your husband and friends, you set up a communal living project in the Catskills, the Mutual Aid Society. How does it compare, so far, with sites you visit in the book?

I knew that my desire to perform this research was related to a real, practical inquiry about how to actually transform our lives. The magical thing about book-writing and art-making in general is that it really does change your life in literal ways.

How does it compare? Gosh, I don't know. It arrived from similar questions: If we bought a house and some land for cheap, in driving distance from New York City, how could we mobilize it to make it a collective resource for others, and in doing so lower the overhead for things that would be impossible or too expensive for us and any of these people to do individually?

First, we ran it as an informal artist residency and soul retreat for people at request. Then, during Covid, it became an emergency boarding house and space of relief for folks participating in protests in the movement for Black lives, as well as a laboratory for new enterprises for folks who were temporarily unemployed. Now it's more of a cooperative artist's residency, something like a shared resource for an extensive network of collaborators. It is also my home.

We keep the organizing principles pretty practical, rather than ideological; there's a lot of shared labor, but it's not that organized; there have developed lots of rituals and holidays specific to the life of this place; and I've watched people make extraordinary things that they otherwise might not have. I've seen lives change. We've also suffered enormous loss, heartbreak and failure.

I hesitate to describe anything too pointedly because it is always changing. And that's a principle I gleaned from my research: nurture change, let go of authorial intent, choose the person not the idea, but make sure that at any moment that basic goal is being met: to have, through collectivity, a more luxurious and creative life for a lower overhead than we had before.

I was struck by the line "All books are written backward." Covid and caring for your disabled father-in-law were unexpected factors as you researched and traveled. How did the finished book differ from the one you'd intended to write?

What a great question. When I began the book years ago, I dreamed, I think, that I would finally stop writing weird hybrid messy narrative nonfiction and instead produce a really focused and tight pop-nonfiction book about this history. As always, there is so much I could add.

I started the book thinking that I was writing my way into one kind of story about my life--one where I would go on this wild research journey, marinate in my findings, tell people thrilling things about all that might be possible, stay married to my husband forever, have children, buy a house that we attempt to use in this cooperative way, but likely it falls away and we get subsumed into the very thing I was decrying.

I really thought that's where the journey of the book was going to take me. Instead, it took me somewhere way weirder, way cooler, way messier, and so the book, too, is weirder, cooler, messier, more surprising, more beguiling, more adventurous than I ever thought it could be. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader and blogger at Bookish Beck