|

|

| (photo: M. Gafarova) | |

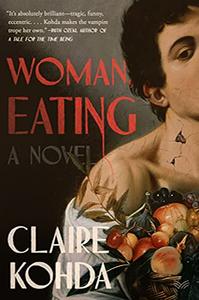

British writer and musician Claire Kohda reviews books for the Guardian, the TLS and elsewhere. She recently spoke with Shelf Awareness about her own debut, Woman, Eating: A Literary Vampire Novel (HarperVia, $26.99; reviewed in this issue), starring Lydia, a recent art school graduate starving as much for belonging as for blood.

Although she is a vampire, Lydia has many "human" worries and insecurities. Why was it important for you to tell a vampire story in this way?

I wrote this novel just under a year into the pandemic; for all of us, our worlds had shrunk. Lydia--the isolation she feels as a vampire living in a world of humans--came out of that time. We need human contact to feel human ourselves. I had my partner and my cat, but the longer lockdowns went on, the more I felt like an animal, living in a little den, creeping out sometimes, but fearing other people. When things started opening up again, I think a lot of people felt like they'd forgotten how to exist in human society. That's Lydia's reality; she's always aware of what makes her different. It's like she's living in a world that isn't designed for her.

The vampire, as a mythical figure, is inherently in between multiple things. When a vampire is turned, it retains its human body and its human memories, but gains this demonic appetite; so, it exists between human and demon. It exists between life and death, good and evil, too. Vampires, traditionally, also can't eat food. They have to drink blood to survive. And, for us humans, food is so crucial, not only as sustenance, but culturally--it's a form of communication: we pass down recipes from generation to generation, we share food with friends and family. The vampire has none of that. What would it really be like to exist like that?

Lydia is both mixed-race and a vampire and feels like an outsider in all her worlds. What was the inspiration to share this perspective?

Ultimately, the only thing that sets a vampire apart from a human is diet--and I found that fascinating. Cuisine is so often used as a means to Other people from Asian cultures. We saw it in James Corden's "Spill Your Guts" segment on the Late Late Show--Asian cuisines are presented as disgusting and weird, and that rubs off on how people perceive Asian people. But Asian cuisines are also often perceived as crueler, too, and therefore the people are perceived in the same way. Despite my being a vegan, strangers (and sometimes people I know) who find out I am part Japanese will ask me about, and sometimes even hold me responsible for, whaling, or dog meat farms in other parts of Asia.

In reality, Lydia is no different from us. She is as human as can be. She cares about being good, she even sources her pigs' blood from RSPCA-certified farms. But if she revealed herself to be a vampire, people would see her as a monster, they'd fear her. That fascinated me--the idea of creating something so solidified in our minds as being monstrous that actually is the opposite. She's relatable, and she's deeply empathetic and caring. Lydia is just a different species to us; she's a kind of manifestation of what it's like to be different, and of what it's like to be feared or to struggle with your identity, because of that difference.

In reality, Lydia is no different from us. She is as human as can be. She cares about being good, she even sources her pigs' blood from RSPCA-certified farms. But if she revealed herself to be a vampire, people would see her as a monster, they'd fear her. That fascinated me--the idea of creating something so solidified in our minds as being monstrous that actually is the opposite. She's relatable, and she's deeply empathetic and caring. Lydia is just a different species to us; she's a kind of manifestation of what it's like to be different, and of what it's like to be feared or to struggle with your identity, because of that difference.

You wrote this around the onset of the pandemic, when there was an increase in Asian hate crimes. Did any of that influence your writing?

Yes, definitely. I wrote Woman, Eating at the end of 2020. It had been almost a year of increased hate crimes against East and Southeast Asians. My mum, my Asian friends, fellow Asian musicians--all of them had experienced at least some form of racism during the pandemic, whether it was a boss wondering out loud if they should not have shifts in their public-facing job because their Asian-ness might put customers off, people blaming Asians for the pandemic, telling them to get off trains, or physically assaulting and verbally harassing people of Asian heritage. I believe it fed into what I wrote.

There's nothing like hearing about racism experienced by a parent that makes you feel a confusing mix of two emotional extremes--rage and anger, but also helplessness and futility. Wanting to defend that parent but also knowing that racism is deeply rooted, and anything you do won't fix the wider problem, can be so debilitating and exhausting. Lydia is like an embodiment of those two feelings--she's got the power and strength to be able to retaliate, but she's also got a lot of things that weigh on her (looking out for her mother, the legacy of colonialism in Malaysia both by her father's and grandfather's countries, racism in the U.K.). At times, they seem like physical weights that push and hold her down and prevent her from doing anything.

Lydia herself is affected by the intersection of sexism and racism. She is preyed on by a man who preys on women, but who also collects "world art" and exoticizes and consumes other cultures. Only recently have I felt that I've had a voice and a platform as a person with Asian heritage. When Lydia is starved of blood, and she has too little to feed to her larynx, she loses her voice. I wanted to explore how we can feel like we have no voice, but then discover we are still powerful, and to find that voice again.

Another intriguing element in this story is your exploration of elitism in the art world. What inspired you to set your story in this culture?

My dad is an artist from a working-class family, and he struggled a lot--first working as a pub sign painter, then a tomato picker and as a gallery assistant, all the while making sculptures in his spare time. Eventually, in my late teens, he found success. Now, his work is everywhere, collectible and well-loved. However, I saw my parents struggling to make ends meet, even while his work was in some of the top art institutions in the world. So, my inspiration for setting the book in the art world was this--my family's experience of the art industry, and my disillusionment with it; but, also, my continued love of art. Art has, for as long as I can remember, enriched my life. But the art industry is vampiric. Lydia loves art; and a lot of this book is about her discovering herself through it. But the art industry, particularly those in power, have a vampiric presence in the novel.

A book that has a vampire in it could easily be categorized as horror, but Lydia isn't really the thing to fear in this novel. It's the humans around her. --Grace Rajendran, freelance reviewer and literary events producer