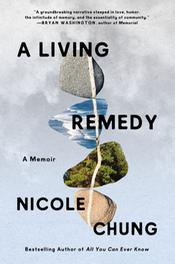

Nicole Chung's lauded 2018 debut, All You Can Ever Know, examined her identity as a transracial Korean adoptee and her reconnection with her birth family. Chung extends that same raw intimacy and empathic insight with which she illuminated bonds of blood to A Living Remedy (reviewed in this issue; Ecco Press, $29.99), in which she explores her relationship with her white adoptive parents, her homogenous Oregon upbringing, her relocation East and the devastating loss of both father and mother over too few years.

Nicole Chung's lauded 2018 debut, All You Can Ever Know, examined her identity as a transracial Korean adoptee and her reconnection with her birth family. Chung extends that same raw intimacy and empathic insight with which she illuminated bonds of blood to A Living Remedy (reviewed in this issue; Ecco Press, $29.99), in which she explores her relationship with her white adoptive parents, her homogenous Oregon upbringing, her relocation East and the devastating loss of both father and mother over too few years.

Writing A Living Remedy must have meant reliving some of the worst moments of loss. How did you prepare?

I honestly wasn't prepared because this isn't the book I thought I'd write. When I sold it, I knew it was going to be about family and leave-taking and loss, the ravages of grief and financial precarity and our broken safety nets. But at the time, my mother was in remission [from cancer], and I expected to focus on writing about my experience of losing my father, and to have my mom actively involved in helping me remember. She and my dad were both so supportive of my first book. But I'd only written about a third of the book when my mom's cancer came back. Then she started hospice care right as the entire country was entering pandemic lockdown.

How did you cope through the grief while writing about such loss?

I put the book down for months while I tried to care for my mom and do what I could from afar. She died in May 2020, and I probably didn't pick up the manuscript again until the fall or early winter. I realized that I was telling a very different story of loss and family now. I was traumatized and grieving and at several points didn't know if or when I'd manage to finish at all.

I think I only managed to write because grief, the pandemic, and many other changes in my life had forced me to understand that I was a human being, not a machine, that I needed to give myself some grace. I have always just sort of put my head down and powered through. But with this book, I was sometimes writing about the harmful effects of doing just that, the challenges of grieving under capitalism. I knew I wasn't alright and hadn't been since my dad's death. I couldn't just compartmentalize to get this book done. I had to work with my fragility, my brokenness, my humanity, and not just fight those things for the sake of "art."

I told myself, every day, that if I couldn't write that day, it would be alright. And that if I couldn't write this book yet, that was alright. Eventually, I figured out how I needed to frame the story--it is really a story of my mother and me, now, and still, but with a different structure than I'd planned. I think writing every day helped me come back to my life and myself in the midst of the deepest grief I'd ever experienced. I don't think writing is therapy, and writing this book wasn't therapy for me. But I think it did help me find a lot of compassion for the person I am as my parents' daughter, as the child who lost them and has to figure out how to go on without them. I'm still recovering from their deaths and always will be. I'm actually very grateful to my writing practice, for keeping me company in those really long, hard months.

I told myself, every day, that if I couldn't write that day, it would be alright. And that if I couldn't write this book yet, that was alright. Eventually, I figured out how I needed to frame the story--it is really a story of my mother and me, now, and still, but with a different structure than I'd planned. I think writing every day helped me come back to my life and myself in the midst of the deepest grief I'd ever experienced. I don't think writing is therapy, and writing this book wasn't therapy for me. But I think it did help me find a lot of compassion for the person I am as my parents' daughter, as the child who lost them and has to figure out how to go on without them. I'm still recovering from their deaths and always will be. I'm actually very grateful to my writing practice, for keeping me company in those really long, hard months.

What do you think your parents might have said about this book? What's the most important thing you would have told your mother about it?

I don't feel I'm good at predicting how people in my life will respond to the things I write. I remember being so anxious about showing my first book to my parents--my adoptive parents and my birth father--and then everyone was so great about it, I realized I'd been worrying for no reason.

I would have told my mother--both my parents--that this book is everything I am, including my love for them and theirs for me. I hope they'd be able to see me in it, and see that I was trying to tell the truth and honor the life they made possible. I do wish I could share it with them. They weren't strangers to grief, and I think there's a lot they would have understood.

Your young daughters asked when they would be allowed to read your book, now books. What hopes might you have of their reactions?

My older daughter read All You Can Ever Know with me just before it was published--I wanted her first time through it to be with me so she could ask all the questions she wanted to or share how it made her feel. One thing I am always struck by whenever we talk about the past is her enormous sensitivity and empathy; for example, I remember her telling me once that thinking about me being alone in the hospital after I was born, in between families, as it were, made her feel sad. My instinct was to reassure her, tell her I didn't remember it, I'd been fine, etc. But I realized I would be doing that in part because I'd felt pressure all my life to reassure other people about adoption, and sometimes minimize its losses and its traumas. My daughter was so young when she first learned that I am adopted, and it made her feel something instinctive and true, and it wasn't my place to tell her not to feel that way. Talking with both my kids about my family, my grief, things I have been through, has helped me see these things through their eyes and also find more empathy for myself.

You've written two memoirs. "You're not famous... Do you think anyone is going to read it?" your mother commented about your first, and wow, what a resounding YES that was! You've co-edited two essay anthologies, A Map Is Only One Story with Mensah Demary and Body Language with Matt Ortile. Might you consider writing fiction someday?

I always think about what my mom said when I told her I was writing a memoir! It still makes me laugh.

I'd love to write fiction. Growing up, and in high school and college, I wrote a lot of fiction and the most terrible poetry. I only started writing creative nonfiction in my 20s, and then it was many years before All You Can Ever Know was published. I'd love to be able to write fiction for younger readers as well as adults. We'll see!

Since you're a full-time writer now, what might your devoted readers expect next?

Promoting and touring for A Living Remedy will keep me busy. I'm co-editing an anthology of young adult fiction, all stories by adoptees of color, which will be out from HarperTeen this fall. I've outlined a novel--who knows if I can write it! I hope I have time to figure some of this out after book tour. --Terry Hong, BookDragon