|

|

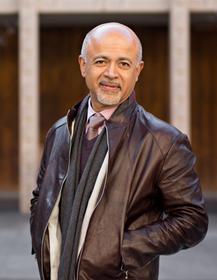

| (photo: J. Henry) | |

Abraham Verghese, M.D., MACP, is the author of the bestselling novel Cutting for Stone and two memoirs, My Own Country and The Tennis Partner. He is the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor and vice-chair of the Department of Medicine at Stanford University. His second novel, The Covenant of Water (Grove), spans seven decades and traces the epic story of a family in southern India afflicted by a mysterious condition: at least one person in every generation dies by drowning.

Tell us about the inspiration for The Covenant of Water.

After I wrote Cutting for Stone, there was some interest in my writing a follow-up, but I just felt that story was done. I've always felt that geography is a character in the story, and I'm also fond of the saying that geography is destiny. My life and my parents' lives are a great example of that. My parents were born in south India, but they left for Ethiopia because of lack of opportunities to teach in their home region. They met and married there, and I was born. I also think of my coming to America eventually as changing my destiny. The places I've lived have shaped my life.

I wanted to locate this book in a new geography, and I was moved to do so by a document my mother wrote. When my niece was five years old, she asked, "Ammachi, what was it like when you were a little girl?" So my mother began writing this longhand description of her childhood, with illustrations--she was a very good artist. It ended up being a 100-page-plus document, with familiar stories that she told her sons. That gave me the impetus to set the story in Kerala. My mom lived until age 94, and she knew I was writing the book. She kept calling me up to remind me of things, sometimes forgetting that she'd already told me about them the day before!

What was it like to explore Kerala, and this idea of "home," in fiction?

The community we come from is a tiny one: a group of Christians that date their Christianity to St. Thomas's coming to India in 52 AD. Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things is set there, but otherwise it is not much explored in fiction. Home was a very different concept then. Your home was not only the place you lived, but also the source of your sustenance, your food, your community, your whole life. So when you moved house (as a young bride, for example), you were being transported to an entirely new place where you would live the rest of your life.

I feel, in a strange way, kind of homeless. I was born on one continent; I live on another. I have family in various places. I suppose that sense of being a perennial outsider is an advantage when I write: you become an astute observer of different cultures, the way people interact. And yet I'm always envious of people who have a home and multiple generations of family in one place.

I feel, in a strange way, kind of homeless. I was born on one continent; I live on another. I have family in various places. I suppose that sense of being a perennial outsider is an advantage when I write: you become an astute observer of different cultures, the way people interact. And yet I'm always envious of people who have a home and multiple generations of family in one place.

Big Ammachi starts out as a child bride, but becomes the matriarch of Parambil. How did you develop her character?

I just fell in love with her as she began to grow and develop. And it was difficult to convey: even though these [arranged] marriages are happening when women are much too young, they are often taken into a family, not just thrown into the clutches of some man. Being married meant a very sad day when they left their childhood home and moved to another house, but they became part of the family there. My great-grandmother and my grandmother were married this way. I'm not recommending it as a way of life, but it wasn't what [modern-day] people would imagine. I took particular pleasure in demonstrating how this inauspicious-appearing marriage became a wonderful relationship, in the end.

How do you decide how much medical detail to include in your books?

I've always been drawn to books that are intensely procedural or technical about a field I don't know much about. I think that explains the popularity of police shows and hospital shows, and Tom Clancy writing about submarines. I think medicine is nothing more than life-plus-plus: life at its most acutely intense, and intensely observed, moments. It's not like submarine technology; it really does involve all of us in a visceral, bodily way. I'm trying to build on the curiosity we all have about the body and what it does. It takes a good editor to tell me whether I'm overdoing it or not doing it enough.

Part of the narrative revolves around a leprosarium. Can you talk about that?

Growing up in Africa and India, leprosy was a common thing to see in the streets. When I got to medical school, some of the most interesting research was being done in the leprosy institutes. A lot of our understanding of T-cell immunity, for example, came from leprosy research. The capacity of leprosy to invade the immune system led to a number of amazing advances in the medical field.

Diseases carry a metaphor, of course. Prior to HIV, leprosy was the disease with the most striking metaphor, carrying shame and repulsion. I felt during my years working as a doctor in East Tennessee and El Paso, Texas, that I was dealing with two diseases: HIV, and what society thought about it. That was crippling in its own way, and led to suicide in more than a few patients. Many of them couldn't deal with the notion of living with this disease and being shunned and shamed.

How do Indian politics--wars, colonization, the Naxalite movement--affect the characters' lives?

That was a delicate and interesting thing to convey. Communism is like a third rail in most of the West, and it's hard to think of Communists as a legitimate political party who get elected, and come in and out of power, like other parties. It was born out of a tremendous inequality between the landed castes and these downtrodden people. After finally ridding India of this colonial power, it must have felt intolerable to still be in shackles. But the Naxalites didn't really succeed in coalescing and becoming a movement, the way that Communists did in China. For the most part, these movements have not lived up to their promises, and people have to deal with the disillusionment, too.

What do you hope readers take away from the novel?

I think good fiction, when it works for us, is conveying a kind of truth. Our experience in the world is limited, but you read novels and you become aware of larger truths than you might understand in your own life. Camus said, "Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth." This is a story, but it's also conveying some truth about our lives.

Working in medicine, one has a strong sense that life is a fatal disease--it's a terminal condition. None of us survive it. One of the only ways to buy yourself time is to enter the world of a novel. You explore different places and meet the characters, and decades pass, and then you put it down and it's Tuesday! I always feel that I've bought myself some extra time in this life when I enter the world of a novel. I hope my readers feel that as well. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams