|

|

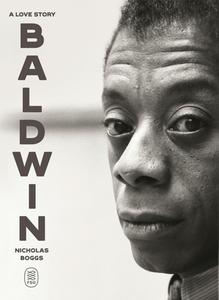

| Nicholas Boggs (photo: Rachel Eliza Griffiths) |

|

Nicholas Boggs is a writer, independent scholar, and author of the biography James Baldwin: A Love Story (Farrar, Straus & Giroux; reviewed in this issue). He has been the recipient of grants and fellowships from the NEH, the Leon Levy Center for Biography, the Whiting Foundation, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Gilder Lehrman Center and Beinecke Library at Yale. Most recently he was the 2024-2025 John Hope Franklin Fellow at the National Humanities Center. He resides in New York City.

Given the extensive scholarship on James Baldwin, what compelled you to undertake this project now, particularly with a focus on his queer identity?

This project didn't become a biography until about eight years ago, but it's a project that I've been working on in one way or another for almost 30 years, since I was an undergrad and I discovered Baldwin's out-of-print [children's book] Little Man, Little Man.

There was this incredibly important biography by David Leeming (Baldwin's assistant and close friend) that was published in 1994, and none of my work, or the work of anyone interested in writing about Baldwin, could do what we do had it not existed. In it there was this one paragraph about that children's book, and it mentioned French artist Yoran Cazac in passing, but it sort of it made it seem like they were probably lovers, but it wasn't exactly clear.

So I found the book at the Beinecke and immediately fell in love with it. Then I wrote the first e-mail of my life to David Leaming, because I wanted to write my senior thesis about this children's book. He wrote back a very nice e-mail, "I never met Yoran Cazac, I think he's probably dead."

About seven years later, I wrote e-mails to art historians in Paris. Months afterward, the phone rings in my apartment in Brooklyn. It's Yoran Cazac calling, saying "I'm alive. Come to Paris. I have many stories to tell you about Jimmy." The reason this relates to the question about queerness, and my interest is that I was very interested in Baldwin's life, particularly his love for other men. I mean love in an expansive sense, right? Not just erotic love, although it could often be that. It's also familial love, fraternal love, kinship, really, beyond the biological. It's also the love he had for his mentor, Beauford Delaney, who he called his "spiritual father." I could tell that this had a huge impact on his life and work, but there were big gaps in how we understood this biographically, and I suspected that Yoran Cazak represented one of those gaps.

However, Baldwin has a quote in a later interview where he says the word "gay" wouldn't have meant anything to his lovers. And this was true, probably, of Lucien Happersberger, his great love, who like many of his lovers was primarily attracted to women and often married them. But I knew that queerness as we understand it today does describe how Baldwin lived his life and his relationships with other men, and even how he conceived of his gender later in his life. (His late essay, "Freaks and American Ideal of Manhood" is key here). In this sense, he is truly a queer icon.

But I would never even call, for example, Yoran Cazac queer. And that was both the challenge of my book, but also its great interest for me. Baldwin was always looking beyond the limitations of society's categories when it came to race, sexuality, and gender.

What would you say that Baldwin's role in queer history is, even as he alternately accepted and rejected identifying terms?

What would you say that Baldwin's role in queer history is, even as he alternately accepted and rejected identifying terms?

His role in queer history is simply massive. I mean, it's kind of impossible to overstate.

People often point to Giovanni's Room, how incredible that he wrote and published this novel in the 1950s amid McCarthyism, amid so much homophobia. It took a lot to get it published. He had to take it over to England and then [it] got published back in the States. But just to write it at that moment was extraordinary, that moment in history. This was right after the Kinsey report. There was just the inklings of gay liberation.

But people often forget that even his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, could be called a queer novel. It was really about the conflict between the protagonist, John Grimes, his religious background, and his burgeoning desire for Elisha. In fact, all of Baldwin's novels, if you look at them somewhat closely, are queer novels in sometimes unexpected way. And If Beale Street Could Talk is this classic heterosexual love story between Fonny and Tish, narrated by a pregnant Black woman, but was actually based on his love affair with Yoran Cazac, to whom he dedicated the novel. Fonny is an artist who works with stone, as is Cazac. There were so many correlations between them. So the thing about Baldwin, he's so layered and working on so many levels all the time that you could call all of it queer, even as you wouldn't want to limit it by saying that, if that would seem to suggest that it's not also about the Black family or Black heterosexuality or white masculinity, all the things that Baldwin explores.

Talk a little bit about this intersectionality as it relates to Baldwin.

Intersectionality is a term that was coined by the legal scholar Kimberly Crenshaw. And it's an important term, but Baldwin was dealing with it in literary terms and political terms, you know, from the very beginning, when he was famously asked what was it like to grow up, Black, poor, and gay. And he said, "I hit the jackpot." He was talking about that--he'd hit the jackpot of intersectionality, as an artist, in terms of the unique perspectives that he that he experienced. Baldwin was working way ahead of his time in terms of how we think about race and gender and sexuality, and that's partly why he's with us so much today.

How did Baldwin's intersectional position give you insight into his activism, most notably in that incident you recount with Bobby Kennedy and the panel of prominent Black figures?

This is where his sexuality became very complicated, because to be the kind of public voice for Black America in that moment, it was important that he not be seen as queer. Even though he was never in any kind of closet, publicly he would sometimes rhetorically make statements like, "I have to protect my wife." People take that literally, but he's being rhetorical.

His queerness is bigger than just being in a closet or out of a closet. His insights into interracial sexuality and into how miscegenation is at the heart of American history and racism, the enforcement of miscegenation through enslavement, and then the disavowal of it, and the sort of anxieties it produces for white Americans in particular--that comes out of his insights into sexuality, which he was thinking about so closely because he'd grown up "menaced"--and that's his word--by the category of sexuality.

This interracial history was the one that had to be confronted by white Americans in order to come to some kind of awareness of the fact that they were not innocent. That's his really important term, that he brings up repeatedly, that the idea of innocence constitutes the crime. The idea that white America has not faced the fact that they inflicted and/or benefited from the history of slavery was something that he was hitting us over the head with, thank goodness, again and again.

But Baldwin wasn't looking for integration. Integration suggests that Black Americans are supposed to seamlessly integrate right into white culture, into white norms, or that gay people, queer people, are going to integrate into the dominant culture through gay marriage or whatever, which is fine, but he was not interested in integration. He was interested in a kind of transformation and mutual recognition.

Sometimes there's like two images of him. One is the civil rights icon, and the other is this kind of tragic gay figure who never found love or wasn't happy. And you know, certainly he had his struggles, as we all have, but he also had immense love, immense community, immense laughter. That's important to remember, that all of that happened--the fullness of his life. And I really wanted to capture that in my book. --Elizabeth DeNoma, executive editor, DeNoma Literary Services, Seattle, Wash.