|

|

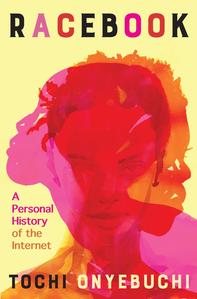

| Tochi Onyebuchi (photo: Christina Orlando) |

|

Tochi Onyebuchi is the author of Harmattan Season, Goliath, and Riot Baby, as well as young adult novels, including War Girls. His collection of essays, Racebook: A Personal History of the Internet (Roxane Gay Books; reviewed in this issue), explores the intersection of the Internet and identity in a series of chapters connecting topics such as video games, social media, and race.

This book is such a fascinating combination of subjects we love to talk about (video games, social media, replicants) and topics of critical importance (race, gender, social justice). Did you set out to write an essay collection on this particular intersection of ideas?

Some of these essays had been out in the wild before I started this collection. Looking at them I saw hints of a through line in the idea of a holistic self and how the Internet can fracture that. It allowed me to get an essay on Afrofuturism into the same collection as an essay on Call of Duty. We contain multitudes, and I wanted to write about the role of the Internet in allowing us to or preventing us from expressing that.

You say that the Internet can fracture the self--can you explain?

You say that the Internet can fracture the self--can you explain?

When you get on the Internet you can feel like a commoditized data point, like you're just one slice of your identity. All the rest of you--your favorite band, the school you went to, all of that other stuff--gets relegated to the sidelines. It changes how we perceive ourselves.

I'm interested in the idea of "emotional contagion" in social media, something you talk about in the opening essay. What does that mean, and why does it matter in our age of ubiquitous social media?

I think we've known for a long time the effect that being chronically online can have on a person. If all the people around you are feeling awful about a particular thing, it's impossible not to be affected by that. But now it's no longer just people in our immediate social circle that can affect our moods, it's anybody.

In the essay "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream," you write about Black people killed by police, as well as ISIS decapitation videos: "The murder is the severing of the head. Social media is the pike on which it is planted." That's such a powerful line.

People shared those videos with noble intentions and a desire to educate others. But it had a multitude of effects. It can be massively triggering to people from those demographics. There's no right answer about any of this stuff, but in that period in 2020 a lot of media was being shared without regard for the different ways it could be affecting people. The way social media works makes it hard to avoid. At the time Facebook was autoplaying videos on people's newsfeeds before they had a chance to pause it or know what was happening. I don't know if I have conclusive thoughts on what it means for these to be shared so pervasively, but all of these thoughts were at work in my head when I wrote those sentences.

In "White Bears in Sugar Land," you discuss N.K. Jemison's landmark Broken Earth trilogy in the context of whether "Authors from marginalized backgrounds may, with varying degrees of success, deny the more pernicious aspects of American publishing and refuse to write their marginalizations, to allegorize them even, or to reduce themselves and their demographic to suffering. What matters is the choice." Why is that series such an important example to consider?

First, they're just so good. But I related to those books, too, because they're so nakedly political and dealt explicitly with the nature of oppression, with vengeance, and the ways in which vengeance and justice can braid together but also diverge. So much of that felt so revolutionary on the page.

But that idea around the choice being what matters was another seed for where this essay collection came from. I looked back at the books I've written and wondered if the self that initially fell in love with writing would recognize the writer that I'd become. I felt duty-bound to write them. There were so many other topics I'd wanted to write about. I didn't know if that earlier me would recognize the writer that I am today, and I wasn't sure how to feel about that, so I decided to write an essay collection about it.

You challenge ideas about what genres should be political. Why do you think there's a notion that speculative fiction isn't a place for politics--and is that changing?

I think it's been changing for a while. There have been bits of upheaval that have gone through the industry and the push-pull has been there for a while now. I think one of the ways to see it is in who is able to write what and who is being celebrated. Seeing change there makes me optimistic for the genre.

You tell a story about someone in an early writing workshop with you intuiting something about your personal life from your writing. How much of yourself do you think ends up in your work?

I'm such a poor judge of that. There's always more of me in my work than I think there is. In the very beginning, I was writing about assassins and samurais. I thought it had nothing to do with me, though even that had me in it. But in the summer of 2013, when I was doing human rights work in the West Bank, I wrote a short story that would eventually become Goliath. It was the first time I had written about Black people. It felt to me that this story was leaps and bounds above what I'd been doing before on a craft level. It seemed that incorporating more of myself could result in better work.

Racebook is just packed with millennial nostalgia. Tell me, what was the best decade and why was it the '90s?

It absolutely was, particularly it was the best decade to have grown up in the U.S. We could get off school, no parents at home, and just go chill at a neighbor's house. People in the neighborhood just trusted each other like that. We could still, by and large, trust institutions. Life at the time was so Edenic. There were trusted common spaces, so I could spend the whole day alone at the YMCA then go straight to the public library. Of course, I'm speaking to my own very particular experience, but things felt simpler--and we had PBS.

Of course, I have to ask you for book recommendations. What three books should we all add to our lists?

I read The Savage Detectives by the late Chilean author Roberto Bolaño maybe a year or two ago. It's been a long time since I've been surprised by a book, whether it's structural or plot-wise or what have you, but that one was nothing but surprises. Impeccable on a craft level, and it's a great distillation of everything that's great about Bolaño.

My second recommendation is one I always include when I get asked this question. A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James, which is maybe the most audacious book that's been published in the last decade. It's As I Lay Dying, but with the central event being the 1976 assassination attempt of Bob Marley and it's something like 85% in Jamaican patois.

My third book is The Parisian by Isabella Hammad, which tells the story of a young Palestinian man in the early 1900s who goes to France to study to become a doctor. It becomes an elegiac portrait of early Palestine, and it's such a different portrayal of that place than we usually get. --Carol Caley, writer