|

|

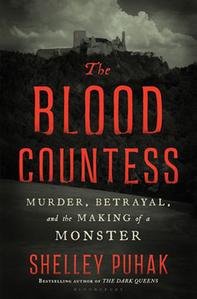

| Shelley Puhak (photo: P.B. Miles) |

|

Shelley Puhak is the critically acclaimed author of The Dark Queens: The Bloody Rivalry That Forged the Medieval World. Her essays have been included in The Best American Travel Writing and selected as Notables in four consecutive editions of The Best American Essays. She is the author of two books of poetry, including Guinevere in Baltimore, winner of the Anthony Hecht Prize. The Blood Countess: Murder, Betrayal, and the Making of a Monster (Bloomsbury; reviewed in this issue) separates the myth and misogyny that fuels dark fascination surrounding one woman from the 16th century.

How and why did you come to Countess Elizabeth Bathory as the subject of your next book? What inspired you?

I first encountered the canonical Bathory legend in my 20s, while exploring the many castles of Slovakia. When, many years later, I learned that more Central European scholars and historians were questioning that legend, I took note. I've always been a sucker for a good unsolved mystery, but this case really began resonating with me as I watched conspiracy theories take hold and disinformation campaigns be waged in our own day and age.

My first book, The Dark Queens, took on two women who hardly anyone has heard of. It was fun to flip the script this time around and write about a woman who is very well-known and show how we've got her story all wrong.

What type of new evidence did you uncover to overturn the accepted myth/legend of Bathory as a diabolical serial woman-killer?

Letters between Elizabeth and her family, friends, and her servants, as well as additional correspondence about Elizabeth, such as between the king and the man prosecuting her case. There were also court cases and documents about other members of Elizabeth's family, as well as records about some of the people who testified against her.

Other evidence was hiding in plain sight. When I commissioned new transcriptions and translations of existing materials, I discovered quite a few errors that had led to mistaken assumptions and misreadings.

How did religious conflicts of the era add to Elizabeth's problems, specifically the allegations of murder?

As different denominations battled for power during the Reformation, their rhetoric became increasingly hyperbolic. People labeled their opponents not just agents of the Devil, but secular criminals. Bishops, priests, and town officials called one another thieves, fornicators, and, quite often, "murderers." So this accusation was already being bandied about very regularly.

The religious conflict also spurred debates over medical care. Was it permissible to still treat illnesses and injuries? Or should you only try to pray them away? And who, exactly, was supposed to be recording deaths and overseeing burials? In such a charged environment, when someone died unexpectedly on the Countess's estates, it was difficult to sort out what was misfortune, what was medical malpractice, and what might have been murder.

Seventeenth-century Hungary was a wildly multicultural place, and Elizabeth showed great toleration for differences in (Christian) belief and practices. Do you think her progressive stance threatened the male-dominated order of the Church, no matter whether it was Calvinist, Catholic, or Lutheran?

Seventeenth-century Hungary was a wildly multicultural place, and Elizabeth showed great toleration for differences in (Christian) belief and practices. Do you think her progressive stance threatened the male-dominated order of the Church, no matter whether it was Calvinist, Catholic, or Lutheran?

Yes, absolutely. It also was a threat to the Hapsburgs, the foreign dynasty ruling the country at the time, who needed to prevent Hungarians from uniting against them.

As a widow with married daughters who had large estates abutting her own, is it fair to surmise that Elizabeth's extensive land holdings triggered the whisper campaigns by her enemies?

Her land holdings definitely made her an attractive target, although they were not the only reason she was targeted. I approached this book as a whodunit: If Elizabeth Bathory was indeed framed, who was the plot's mastermind? A couple of possibilities presented themselves. The whisper campaign could have started because of local grudges: Was it fellow nobles, hoping to score her land? A few underlings who were embezzling funds and wanted to avoid being caught? A witch-hunting pastor hoping to advance his career? Or was the plot much bigger?

What is often overlooked is how embroiled Elizabeth was in the tumultuous politics of the time and how she was under suspicion of treason. First, her family was involved in a rebellion. Then, her young and charismatic nephew became the prince of neighboring Transylvania; there was genuine fear that this new prince would invade and overthrow the Hapsburgs. This political context explains one of the other accusations leveled against Elizabeth Bathory, that she was trying to assassinate the king.

Were people really convinced she was guilty of murdering young girls and bathing in their blood, or was this just an elaborate and effective attempt to gain control of her?

It was fascinating--and frustrating--to parse all of these different character's motives. Did all of the people spreading these rumors really believe them? There were a few people, like the witch-hunting pastor, who seem to have sincerely believed that Bathory was a child-snatching cannibal, just as they believed their neighbors were witches or werewolves or the minions of Satan. There were plenty of other people, however, who took advantage of a moral panic to benefit themselves.

One of the "best" ways to impugn the character of a powerful woman was to make allegations of witchcraft, which your book explores. Why was this tactic so successful?

Women were not supposed to be political creatures, which made it difficult, and sometimes legally impossible, to charge them with treason. You also couldn't challenge a female political opponent to a duel or face her on a battlefield. The best way to sideline her? Impugn her virtue or charge her with witchcraft. So many high-ranking women were accused of witchcraft in this era, ranging from queens to noblewomen, including other members of Elizabeth's family.

This was a time where anti-science and reactionary forces seemed to run amok. Can you explain how this theme should concern people in modern times?

I think we are generally not prepared for the speed with which things can fall apart. People who have put their faith in the rule of law, in logic and reason, sometimes end up unable to act in time because they are incredulous, frozen in disbelief.

There are two possible horror stories in the Bathory case. One is that an individual who publicly campaigned to protect the vulnerable was also the head of a criminal network that trafficked, tortured, and murdered children. The other possibility is that a peaceful and progressive community turned on itself. Ordinary people--educated, kind, good people--were manipulated into believing that their neighbors were literal monsters. For me, the second possibility is equally, if not more, chilling.

There are many representations of the countess in books, movies, and television. What is the biggest thing about her life these portrayals get wrong? And what do you hope your readers will come away with after reading your book?

The bloodbath! There are so many portrayals of the Countess bathing in virgin blood, usually in an attempt to stay eternally young. Elizabeth Bathory was accused of many things--witchcraft, cannibalism, treason, and murder--but none of her contemporaries ever mentioned her bathing in blood. That sensational detail was a much later addition, inserted by an odd little priest with an agenda of his own.

My goal for this book--beyond solving this historical cold case once and for all--was to help readers reflect upon how disinformation campaigns are waged, how myths get made, and what, exactly, historical justice might look like today. --Peggy Kurkowski, book reviewer and copywriter in Denver