Friday, October 7, 2022

This week, we review Newbery Medalist Kwame Alexander's The Door of No Return, a "foreboding yet mesmerizing historical novel in verse"; Celeste Ng's Our Missing Hearts, which uses a "brilliantly envisioned" dystopian U.S. as the setting for her "eerie and prophetic novel"; and, from photographer Carell Augustus, Black Hollywood, a "knockout portrait showcase" of 60 Black leaders from the world of arts and entertainment; plus so much more!

Jonathan Escoffery, the 2020 Plimpton Prize for Fiction recipient, discusses his debut linked story collection, If I Survive You, in The Writer's Life. The book follows what he calls "our hyper-observant Jamaican American hero, Trelawny" and his family striving for more in Miami.

Our Missing Hearts

by Celeste Ng

Political and cultural divisions metastasize into a dystopian U.S. in which dissent is surveilled and heavily punished in Our Missing Hearts, an eerie, prophetic novel from Celeste Ng (Little Fires Everywhere).

Twelve-year-old Bird Gardner has struggled to make sense of the world since the disappearance of his mother, notorious revolutionary poet Margaret Miu, three years ago. His friend Sadie claims Margaret is leading a movement to fight the federal act Preserving American Culture and Traditions (PACT), created as an antidote to a period of violent civic unrest known as "the Crisis." Under this legislation, the government is tearing families apart as children like Sadie are taken forever from parents the government believes to have "un-American" sentiments. Protest art featuring heart imagery and the phrase "our missing hearts," borrowed from a Margaret Miu poem, pops up across the nation and is just as quickly expunged.

When Bird receives an envelope containing a drawing from a folktale his mother used to tell him, he believes she is contacting him. His ensuing quest leads him to missing children and renegade librarians, through a changed and sometimes dangerous New York City, and finally to the truth about PACT, his mother and what makes the risk of raising one's voice worth it.

This departure from the author's usual realm of domestic drama has an occasional glimmer of Margaret Atwood or Fahrenheit 451 but primarily showcases Ng's own ingenuity and range. Brilliantly envisioned, this coming-of-age story asks what it means to be a good parent or a good citizen when every child is at risk, as well as what power art has to challenge injustice. --Jaclyn Fulwood, blogger at Infinite Reads

Discover: This intimate, prophetic dystopian tale, a departure for Celeste Ng, both affirms and explores the power of family and art.

The Pachinko Parlor

by Elisa Shua Dusapin, transl. by Aneesa Abbas Higgins

Winter in Sokcho, the extraordinary first novel, gorgeously translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins, by French Korean author Elisa Shua Dusapin, won the 2021 National Book Award for Translated Literature. The two reunite for The Pachinko Parlor, in which Dusapin's remarkably intricate and lean prose reveals a layered narrative about isolation and displacement.

Claire, a graduate student from Switzerland, visits her maternal Korean grandparents in Tokyo and plans to travel with them back to Korea. Much is immediately lost in translation: Claire's native language is French, and because her grandparents speak Korean and Japanese, their communication relies on "simple English, with a few basic words in Korean." Her grandparents left Korea in 1952, escaping the civil war after surviving the brutal Japanese occupation--a time when speaking Korean was punishable by death. They opened the Shiny, a pachinko parlor, more than half a century ago; her 90-year-old grandfather still works daily while her grandmother stays home, progressively disconnecting from the world. Claire tutors a local child, 10-year-old Mieko, in French while her mother, a French literature professor, works; mother and daughter are the only residents of an abandoned hotel they won't leave in case Mieko's vanished father miraculously returns. Time jumps forward, but any future clarity--perhaps an ironic nod to Claire's very name--remains elusive.

Dusapin sets her novel amid a Tokyo heat wave, brilliantly imbuing the story with a sense of stifling unease. Claire can't connect with her grandparents; her peripatetic parents aren't available; she's estranged from her lover; and any attachment with Mieko is fleeting. Dusapin's spotlight on characters who ache with longing is a dazzling consideration of loneliness. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: The winning writer and translator of 2021's National Book Award for Translated Literature reunite for a stupendous novel about a young woman aching for shared empathy and lasting kinship.

The Winners

by Fredrik Backman

The story "starts right here and ends in less than two weeks, and how much can happen in two hockey towns during that time? Not much, obviously. Only everything." Fredrik Backman (Britt-Marie Was Here; A Man Called Ove) opens The Winners, translated from the Swedish by Neil Smith, with a tease. This, the final novel of his Beartown trilogy, is a big-hearted, epic novel, bouncing between hope and tragedy as smoothly as a puck flying down the rink.

Readers new to Beartown and Hed, the adjacent Swedish towns and hockey rivals of Backman's Beartown and Us Against You, will quickly pick up their culture and bitter history. Backman's omniscient narrator inserts foreshadowing: "Naive dreams are love's last line of defense," he warns on page one. When he writes that "all that holds us together in the forest is our stories," readers are reminded, as the beloved proprietor of the Bearskin bar says, that "everything and everyone is connected around here, whether they like it or not."

The "two weeks" of the novel includes backstories: the unforgettable violent act in the trilogy's second novel; ongoing shady political and business dealings that threaten one town's team and an iconic coach's reputation; deep love between husbands and wives, parents and children; and friendships that span decades. Opening with a fierce storm that finds two women, one from each town, overcoming daunting odds to deliver a baby in the forest, and ending with the introduction of a skater who one day "will make us feel like winners again," Backman brings his saga to an often brutal but ultimately heartwarming and hopeful conclusion. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

Discover: The epic conclusion to the Beartown trilogy will satisfy even those new to Beartown and Hed, towns deep in the Swedish forest whose citizens are obsessed with their rival hockey teams.

The White Hare

by Jane Johnson

Jane Johnson (The Sea Gate; The Tenth Gift) transports readers to rural Cornwall in the years just after World War II in The White Hare, a fanciful novel of family, village life, history, mythology and more.

In the opening pages, first-person narrator Mila, her daughter, Janey, and her mother, Magda, arrive at their new home, a grand but dilapidated Cornish seaside estate, in the summer of 1954. Timid Mila is fleeing an unnamed scandal in London; the irascible Magda has taken charge of their little troop. Janey, age five, is eager to explore her new surroundings, accompanied by Rabbit, her stuffed toy and best friend. The estate, purchased with unexplained but apparently significant funds, has a mysterious history; locals make foreboding remarks and then clam up. "Best not talk about unlucky things too much, or you may attract unwanted attention," Mila is warned. Magda plans to refurbish and open a grand guest house, with Mila to cook and clean. Immediately and surprisingly latching on to their odd household is Jack Lord, a local who is (like all these characters) unforthcoming about his past, but handy with repairs and good with high-spirited, imaginative, clever Janey. Things go bump in the night, there are hints of ghosts and old crimes, and the vicar in town is inexplicably, aggressively sinister.

The White Hare is jam-packed with slowly released secrets: those between mothers and daughters, those kept by the villagers, and those locked away within traumatized minds. With lush descriptions of fashion, food and especially nature, Johnson's prose appeals to sentiment and expertly evokes an often-menacing mood. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Discover: Love and mourning, betrayal and hope, ancient legends and modern conflicts come together in the atmospheric Cornish countryside in this engrossing novel.

Which Side Are You On

by Ryan Lee Wong

In Ryan Lee Wong's dynamite debut novel, Which Side Are You On, set in Los Angeles, with its history of race riots, an Asian American college student committed to social justice rethinks how best to live out his ideals in the real world.

Reed and his Brooklyn friends are staunch Black Lives Matters activists. Their latest cause is protesting the killing of a Black man by an Asian American police officer (the actual 2016 killing of Akai Gurley by Peter Liang). Reed has devoted so much energy to following the subsequent trial that he's now on academic probation. In fact, he intends to drop out of Columbia University to take up full-time activism. That is, until he goes home to Los Angeles for a few days.

When his brassy mother picks him up from LAX, they head straight to the care home to visit her mother, who has suffered a stroke. Meanwhile, Reed's mother proceeds to poke holes in her son's self-righteous attitude. She cofounded a Black-Korean Coalition in the 1980s, and knows firsthand that nothing is ever simple; situations that appear clear-cut are more complicated when you get to know people and understand their motivations. Reed's father, a Chinese American employed by a union, shares her history of community organizing. They don't want their son repeating their mistakes.

Full of vibrant characters, this punchy story offers no simple answers to ongoing racial conflicts. The portrait of a sanctimonious young man who wakes up to the reality of generational trauma and well-meaning failure is spot-on. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader and blogger at Bookish Beck

Discover: Ryan Lee Wong's dynamite debut novel weaves timely issues of racism and protest--and much nuance--into a pacy, funny story of generational differences and idealism versus cynicism.

Utopia

by Heidi Sopinka

Heidi Sopinka's Utopia opens at a party with the first-person perspective of Romy, a performance artist, directly addressing her months-old daughter. The evening ends with an unexplained tragedy, and from there the novel jumps forward some months to follow a young woman named Paz, who is now raising Romy's baby and is married to Romy's husband, Billy. It is 1978, and Paz, Billy and all their friends are steeped in the Los Angeles art scene, where sex, drugs and free expression are soured by competition, infighting and wildly different rules for male and female artists. Paz attends women's groups and wishes for a freer life for herself, but many women see her as having taken over Romy's life in decidedly unfeminist fashion. Romy, the more successful and established artist, casts a long shadow. Caring for Romy's baby, lost in reading Romy's journals, Paz finds herself in something of a love triangle with a ghost, and begins to lose grasp of her own life and art. And then a postcard arrives, apparently from Romy. It is labeled "disappearance piece."

Utopia cleverly investigates layers of social issues: feminism and its intersections with race and class; gender roles in life and in art; women's relationships; the artist's relationship to commerce and social justice. The central narrative belongs to Paz, but that narrative is always shadowed by Romy. Sopinka (The Dictionary of Animal Languages) excels in characterization and the evocation of the power of creation. In pursuing her predecessor's mysterious end, Paz must put herself in real danger and explore the very edges of not only art but existence. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Discover: Art, gender, love and friendship are all under consideration in this novel of twisted relationships in the 1970s L.A. art scene.

The Sleeping Car Porter

by Suzette Mayr

Set in 1929 on "the fastest train across the continent," The Sleeping Car Porter is the immersive story of a "run" by 29-year-old R.T. Baxter, a Black gay porter reduced to obsequious servitude and the unrelenting demands of riders. The sixth novel from Suzette Mayr (Dr. Edith Vane and the Hares of Crawley Hall) moves with the train's rhythm, rocking, chugging and whistling from Montreal to Vancouver.

Baxter--or "George," as the white passengers dismissively call him--dreams of being a dentist and calculates every tip earned, anticipated or withheld against his savings for dental school fees. An unforgiving demerit policy puts porters perpetually on notice, and the looming threat to Baxter's security is palpable. With his smile "broad but not too broad," Baxter prepares berths, shines shoes until the leather gleams and answers requests while "sleep pokes him in the ribs." Nevertheless, Baxter's good will suppresses his exhaustion and anxiety. He silently labels passengers: "Punch and Judy" are the pursed-lipped, red-cheeked newlyweds; "Paper and Pulp" the spatting businessmen. A despondent girl flees her overwrought grandmother to cling to Baxter, so he "works one-handed, or... lets her hang off his back." His obsession with dentistry lends comic relief: "He's stuck with her like a raspberry seed caught in a molar," Mayr writes of a particularly onerous passenger. A mudslide delays the train and its impatient inhabitants "an extra day-and-a-half-two-days-he's-lost-count-of-the-days," but climactic plot twists bring Baxter unexpected hope in this unusual piece of historical fiction. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

Discover: An ambitious train porter struggling to meet passengers' demands makes a trans-Canada run in a novel that reveals the class and race distinctions of the 1929 service industry.

The People Immortal

by Vasily Grossman, transl. by Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler

From Vasily Grossman (1905-1964), the master 20th-century Ukrainian Soviet novelist of Stalingrad, Life and Fate and Everything Flows, comes The People Immortal, translated by Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler. The novel--set in Eastern Europe in the early days of Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union--is a tragic but stirring story of enduring against impossible odds. It tracks a single unit ordered to defend its position, with minimal support, against a massive invading force.

Part novel, part at-the-front war journalism and part inspirational propaganda, the novel was surely written in large part to bolster morale during the time when Nazi Germany was at the height of its highly organized, technologically sophisticated powers, the eventual Allied victory by no means assured. Nonetheless, Grossman exhibits keen powers of observation, analysis and humor--and an immense, stubborn affection for the human spirit, even amidst its worst manifestations. This makes the novel a riveting drama that is still boldly critical of dysfunctional military bureaucracy and Soviet magical thinking (its excessive optimism and despair).

In its precise descriptions of military tactics and strategy, its individual human stories--civilians caught up in the maelstrom; enlisted men; military officers, both Soviet and German--and its philosophical reflections, the novel's cross-sectional threads cohere into a striking narrative tapestry. And in its evocative depictions of the characters' past lives, The People Immortal relates the history of a people, a community and a nation, all set in the present tense against (in a dark irony) the beauties of late spring bursting into summer. --Walker Minot, freelance writer and editor

Discover: This rediscovered 20th-century classic from Vasily Grossman emerges from decades of Soviet censorship and repression to tell the story of brave, hopeless resistance in defense of home.

Romance

The Kiss Curse

by Erin Sterling

Erin Sterling (The Ex Hex) returns to the witchy town of Graves Glen, Ga., in The Kiss Curse, a funny, clever and not-too-spooky romance in which competing shop owners go from enemies to lovers. Wells Penhallow is more than ready to leave his family's floundering pub in Wales, so when his overbearing father gives him the opportunity, he joins his brother, Rhys, in the same town in Georgia where he attended college. Gywn Jones--cousin to Rhys's wife, Vivi--runs Something Wicked, a shop catering to the many tourists who flock to the town for its curated Halloween atmosphere. Unfortunately for Gwyn, the newest Penhallow in Graves Glen is none other than her college rival, and he's setting up shop directly across the street.

Sterling establishes the romance early in the novel. This gives readers plenty of time with her two bickering and stubborn protagonists, whose attraction to one another is undeniable. Readers can expect lighthearted shenanigans--a love spell that turns out to be edible body glitter, a talking cat--grounded with a bit of mystery and danger. After Vivi and Rhys head off on their honeymoon, another former classmate arrives with the worst of intentions. Wells and Gwyn must team up to save the town, its magic and the people they love. Sterling treats her readers to Halloween vibes, humor and a bit of heat as these two rivals learn that kissing is a lot more fun than fighting. --Suzanne Krohn, librarian and freelance reviewer

Discover: College rivals become competing shopkeepers--and then something more--when they team up to save the magic and the Halloween tourist town they love in this funny, witchy romance.

Bad Girl Reputation

by Elle Kennedy

Elle Kennedy's strong female leads and heated, slightly dangerous relationships pull readers in for another wild ride of a romance. Though it can be read as a standalone novel, Bad Girl Reputation is the second in the Avalon Bay series; the first novel, Good Girl Complex, introduces Avalon Bay and a group of fiery characters.

Genevieve, after a mysterious disappearance, returns a year later to her hometown of Avalon Bay to face her past. She is there for her mother's funeral and is determined that her homecoming will be brief. With her family's business in need of her help and her ex-boyfriend, Evan, looking for answers as to why she left without a goodbye, Gen realizes that, if she stays, her old life of drinking, partying and avoiding responsibilities will be an easy pattern to slip back into.

Kennedy (Misfit; The Chase; The Deal) introduces Genevieve at a crossroads between her old "bad girl" habits and her new and improved lifestyle. Genevieve and Evan traverse a maze of inflamed emotions amid beach bonfires, sailing races and ice-cream dates that accompany life in the Bay. The dreamy beach town is a backdrop to the alternating perspectives of Genevieve and Evan, who work at forgiving each other and themselves for the mistakes of their past and attempt to propel themselves into a healthy future. Unsure how to be together again without their vices resurfacing, the novel follows their efforts to grow into themselves without losing who they are--or each other. The depth of Kennedy's characters creates a bond that is hard to let go of when the novel ends. --Clara Newton, freelance reviewer

Discover: A challenging yet heartening homecoming novel explores how a former "bad girl" confronts the unhealthy habits and temptations of her past.

Biography & Memoir

Listen, World! How the Intrepid Elsie Robinson Became America's Most-Read Woman

by Julia Scheeres and Allison Gilbert

Elsie Robinson (1883-1956) herself would approve of the snappy writing from Julia Scheeres (A Thousand Lives) and Allison Gilbert (Parentless Parents) in Listen, World!, the reverent biography of the poor Victorian girl who became a beloved, nationally syndicated columnist. Robinson was "in love with words" since childhood, but poverty and misogyny dimmed her hopes of becoming a writer. After being raised in the frontier village of Benicia, Calif., she wed a dour New England widower in 1903. In her memoir, I Wanted Out!, she wrote of society in the 1890s: a "Good Woman was a Wife, Mother, or a Dear Old Maid." The path to her first published work, the tale of a "lariat-swinging, freethinking female entrepreneur," included fleeing her prudish Vermont husband, struggling as a single mother, mining in the Sierra Nevada hills, and near-starvation in San Francisco. At last, a newspaper editor offered her a weekly column--"animal stories, illustrated"--and Aunt Elsie's Magazine for the Kiddies of the Oakland Tribune was born. This led to homemaking and advice columns, her syndicated "Listen, World!" column, poems and more.

A move in 1923 to a William Randolph Hearst-owned San Francisco paper boosted Elsie's career: she became "the Chief's" highest-paid newswoman. Even though she eventually confronted the powerful publisher about pay inequity, she remained at her typewriter. She left two months of material when she died, having produced approximately 9,000 stories in her 40-year career.

Scheeres and Gilbert liberally insert Elsie's colorful writing throughout their detailed biography and emphasize that Robinson's is not a rags-to-riches story, but one of a resilient, forgotten and "venerable American icon." --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

Discover: This biography, spanning the Victorian era to the 1950s, chronicles the adventurous life of newspaperwoman Elise Robinson and includes quotes from her columns, stories and poems.

Curing Season: Artifacts

by Kristine Langley Mahler

Kristine Langley Mahler's Curing Season: Artifacts is an essay collection selected for West Virginia University Press's In Place series, which features strongly place-based literary nonfiction. In these often experimental essays, Mahler considers a brief but powerful part of her youth spent in eastern North Carolina: four years of preadolescence in which the young Mahler struggled with feeling that she didn't belong. While this is arguably a universal preadolescent experience, Mahler's story is indelibly linked to the community in which she lived, made and lost friends, and attended school.

In Pitt County, N.C., the author encounters matters of race and class for the first time. The profitable sale of her family's home in Oregon has enabled them to enter a prosperous suburb where her neighbors attend cotillion. White children, like Mahler, who go to public school are bussed into a majority-Black part of town as part of 1990s desegregation efforts. Her neighbors' families seem to all rely on generational relationships to the place. She feels her outsider status at every turn.

While some essays use relatively straightforward narrative storytelling, others are fragmented, rely on images or borrow forms from other works. Mahler explores astrology, references Joan Didion's famous rational detachment and borrows lines from Margaret Atwood's Cat's Eye and the local history Chronicles of Pitt County. "I grafted my history onto theirs; I twisted the lessons until I could wring out similarities between my past and theirs." Mahler's investigative ponderings on belonging, displacement and a sense of home are both specific to place and universally familiar. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Discover: These experimental essays about place, home and the failed effort to belong are closely tied to Eastern North Carolina, but will resonate everywhere.

Social Science

All That Is Wicked: A Gilded-Age Story of Murder and the Race to Decode the Criminal Mind

by Kate Winkler Dawson

A brilliant killer matches wits with the best minds of the late 1800s in All That Is Wicked: A Gilded-Age Story of Murder and the Race to Decode the Criminal Mind by Kate Winkler Dawson (American Sherlock; Death in the Air). In different circumstances, Edward Rulloff might have become a world-famous academic. Unfortunately for himself and for many others, he also had psychopathic tendencies. He confessed to murdering his wife and, during a robbery, a store clerk. He was also suspected of murdering his infant daughter, sister-in-law and niece. Psychopathy, however, would not be understood for nearly another century.

Rulloff's 30-year trail of crime--the stuff of local legend, which in Dawson's account reads almost like a novel--ended with his public execution in 1871. His case, Dawson writes, became "one of the first 'trials of the century' in 1800s America." A self-taught philologist, Rulloff spent his prison years "shackled... to his desk as he scribbled his deeply researched theories on the origins of language." Rulloff's undeniable genius confounded the intellectual community of the era: many ascribed to classist and racist beliefs that violent criminality belonged to those of other races or the lower classes and believed that an intelligent, middle-class white man was incapable of the acts Rulloff was accused of. The author expertly showcases the polarizing effect Rulloff had on everyone from Horace Greeley to Mark Twain as she analyzes documents of the era. History lovers and true-crime addicts are sure to be mesmerized by All That Is Wicked. --Jessica Howard, freelance book reviewer

Discover: In Kate Winkler Dawson's All That Is Wicked, a brilliant serial killer divides Gilded Age intellectuals on the topic of criminality.

Essays & Criticism

It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror

by Joe Vallese, editor

It Came from the Closet is a highly engaging and thought-provoking collection of 25 essays by LGBTQ+ writers relating how horror films are seen through their queer gaze and how those films informed their gay identities. Many of the essays read as memoir pieces as much as film profiles, but they're all fascinating and well written.

Sachiko Ragosta explains how Eyes Without a Face parallels their own transition story. Will Stockton sorts through his mixed emotions as a kid who loved horror films but is now unsettled by his troubled son's new Chucky doll. Interpreting Halloween as a coming-out story, Richard Scott Larson reflects on the physical and emotional masks people wear to hide their identities. Laura Maw recalls her girlhood crush on the character Annie, a teacher played by Suzanne Pleshette, in Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds. Tosha R. Taylor compares Lon Chaney Jr.'s character in The Wolf Man--someone who can't contain the monster inside himself and whose father believes he can be cured--with her own childhood under her homophobic father and placating mother. S. Trimble's thoughtful essay on The Exorcist admits rooting for the monster; she writes: "Horror helped me love my terrible truths, the things about me that disquieted others."

Other films examined include Hereditary, Pet Sematary, The Blob, Godzilla, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Get Out, the Friday the 13th franchise and Sleepaway Camp, which editor Joe Vallese (What's Your Exit?, with Alicia A. Beale) calls "the at once deeply transphobic and effusively homoerotic cult slasher." This entertaining essay collection is filled with smart observations and touching autobiographical tales. --Kevin Howell, independent reviewer and marketing consultant

Discover: Twenty-five queer writers offer engaging and entertaining essays on how horror films informed their identities and how they read these films through their own gay lenses.

Body, Mind & Spirit

How We Live Is How We Die

by Pema Chödrön

Everything under the sun has the fleeting quality of a dewdrop or a flash of lightning," explains Pema Chödrön, Buddhist nun, spiritual teacher and author of the illuminating How We Live Is How We Die. And the more that people fight to hold that dewdrop in the palms of their hands or attempt to capture that bolt of lightning in a jar, she asserts, the more tired and frustrated they become. Why do they do it? Why do they struggle to arrest the fleetingness of nature? Why is the human species so unwilling to accept the omnipotent force of impermanence? Why do people feel so much suffering in change? Why do they resist life as it is? There are few better guides who get at the heart of these questions than the thoughtful and caring Chödrön (When Things Fall Apart), who utilizes Bardo Tödrol (translated into English as The Tibetan Book of the Dead) in order to walk readers through a journey of self-discovery, universal truth and the meaning of life, death and the time spent in between.

But How We Live Is How We Die is not a self-help book or a secret code to living a happy life. It is the investigation of the religious text that is Bardo Tödrol--and it is a means of transmitting the wisdom and light of that text into the modern world. In a time when people would most like to dwell in the illusion of certainty, Chödrön reminds readers to recognize beauty in unpredictability and to relinquish their grip on a reality that is, and will always be, in flux. --Eamon Stein, freelance reviewer

Discover: In How We Live Is How We Die, Pema Chödrön reminds readers to recognize the unpredictability of life and death and to relinquish their grip on an ever-changing reality.

Gardening

What Is My Plant Telling Me?: An Illustrated Guide to Houseplants and How to Keep Them Alive

by Emily L. Hay Hinsdale, illus. by Loni Harris

Although the meaning of life may be complicated, the ingredients of life are not, especially when it comes to houseplants. Author Emily L. Hay Hinsdale (Never Put a Cactus in the Bathroom) makes it clear at the beginning of What Is My Plant Telling Me?: water, soil and light are the essentials. But what kinds? In what quantities? And for which plants? And do brown leaf tips mean this plant is underwatered or oversaturated? Please help!

Fortunately, this is a guide made to answer those questions and many more. Hinsdale includes helpful general guidance, right from the start, that provides such tips as how to assess soil's moisture level; the purpose of pebbles in a planter; and the proper watering technique. What Is My Plant Telling Me? then shifts to become an encyclopedic guide to the most abundant, recommended and beloved houseplants. With plant-by-plant facts, specific directions and Loni Harris's lovely color illustrations, this is an informative primer for an aspiring indoor horticulturalist; a lifesaver for those who fear their touch means death to all plants; and a timeless resource for the expert living in a home that is various shades of dappled green.

What Is My Plant Telling Me?--written in light, concise prose filled with dry humor and steeped in wise counsel--reads like a comprehensive plant blog of the highest quality, absent any annoying pop-up advertisements. It is a book dedicated to the joyful and wondrous act of caring for life itself in whatever space is available. --Walker Minot, freelance writer and editor

Discover: A detailed but focused guide to houseplants and how to care for them, What Is My Plant Telling Me? is the perfect resource for anyone committed to growing things.

Art & Photography

Black Hollywood: Reimagining Iconic Movie Moments

by Carell Augustus

Psycho, Saturday Night Fever, The Godfather, Carrie, Rosemary's Baby, The Matrix, Bonnie and Clyde, Taxi Driver, Forrest Gump, Breakfast at Tiffany's: Besides being classics, what do these movies have in common? They all have white stars. For the brilliantly conceived Black Hollywood: Reimagining Iconic Movie Moments, photographer Carell Augustus recasts familiar shots from these films and others--as well as career-defining stills of Tinseltown greats--with Black leads. It is a knockout portrait showcase.

For his subjects, Augustus taps more than 60 figures in the world of arts and entertainment. Vivica A. Fox impersonates Old Hollywood's screen siren Veronica Lake. Blair Underwood relives Jack Nicholson's "Here's Johnny!" moment from The Shining. Vanessa L. Williams poses as Cleopatra and is as ravishingly sultry as Elizabeth Taylor ever was. Augustus's book comes from a personal place. A child of the 1980s, he loved movies like The Goonies and Back to the Future. Only later did he "fully understand the implications of dreaming vicariously through those who looked nothing like me," he writes in his introduction.

Black Hollywood can be evaluated and enjoyed strictly for its visual dazzle: the photos are stunning and, while remarkably faithful to the source material, spiked with playful departures. But there are, as Niecy Nash puts it in her afterword, implicit politics in "beautiful Black men and women transforming themselves to embody roles never intended for them." No image in the book has more layers of meaning than Augustus's shot of the dreadlocked Shanola Hampton as Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind, her fist raised in defiance. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: Photographer Carell Augustus recasts familiar moments from classic Hollywood films with Black leads, creating a knockout portrait showcase.

Now in Paperback

Cloud Cuckoo Land

by Anthony Doerr

Cloud Cuckoo Land, Anthony Doerr's highly anticipated follow-up to All the Light We Cannot See, begins in what previous devotees might consider an unlikely time and place: a spaceship partway through a journey to colonize a new planet. In this ambitious novel about the necessity of storytelling for people on the edge of catastrophe, Doerr introduces a dizzying array of characters and settings, from Konstance, a 14-year-old passenger on the spaceship the Argos, to young Anna and Omeir, who find themselves on opposing sides during the 1453 siege of Constantinople; Zeno and Seymour are at the center of a kind of modern-day siege in the present. The characters are connected by the crises they face and by their shared appreciation for "Cloud Cuckoo Land," an ancient, fictional tragicomic Greek text about the persistent human drive to escape suffering and find somewhere better.

Cloud Cuckoo Land possesses a fable-like quality, sometimes skipping through characters' lives in a few pages, in a manner reminiscent of the briskly paced but sweeping scope of the titular Greek text--long passages of which are quoted in between chapters. Thus, readers are elegantly brought up to speed on Omeir's miraculous survival as a child maligned for his facial deformity and Anna's unlikely adventures smuggling books out of a crumbling building before the siege on Constantinople begins. Doerr's storytelling abilities--and the book's fable-like elements--come to the fore as the siege approaches and Anna and Omeir observe a conflict so large it is almost beyond their comprehension.

Cloud Cuckoo Land suggests that the harm people do does not and will not overwhelm their capacity for kindness and bravery. And it argues that stories have the power to bind us together over millennia. --Hank Stephenson, manuscript reader, the Sun magazine

Discover: Anthony Doerr's ambitious follow-up to All the Light We Cannot See elegantly argues that stories have the power to bind us together over millennia.

These Silent Woods

by Kimi Cunningham Grant

These Silent Woods by Kimi Cunningham Grant (Fallen Mountains) skillfully depicts a man struggling with fatherhood and PTSD in an evocative, suspenseful story that gains its strength from powerfully drawn characters.

A remote cabin in an isolated area of the Appalachian Mountains has offered an idyllic way of life but also been fraught with complications for army veteran Cooper and his bright eight-year-old daughter, Finch, in Grant's enthralling third novel. The move was both a spontaneous and well-planned decision for Cooper, whose violent episodes brought on by PTSD had become frequent. After Cooper's girlfriend--Finch's mother--was killed in an accident, her wealthy parents took custody of the then months-old baby. Cooper forcibly took the girl and settled off the grid on land owned by his former army buddy Jake.

Here, no one goes by a last name. Father and daughter hunt, grow some food and raise chickens; each winter, Jake brings a year's worth of supplies, clothes and books that Finch devours. But Jake disappears, forcing Cooper to reevaluate his decisions. He ventures into the outside world, tormented that he will be arrested for kidnapping Finch.

Grant's lyrical writing and a deep understanding of her characters propel These Silent Woods. Isolation has calmed Cooper, though the occasional panic attack still rears; he's unable to rid himself completely of his "wounds on the mind." More importantly, fatherhood has grounded him. He is an excellent parent, though he worries that eventually this life will become "too small" for the inquisitive Finch--fears that are realized when a stranger appears.

Unconditional love and redemption elevate the thoughtful These Silent Woods. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer

Discover: A veteran finds peace in a remote cabin with his eight-year-old daughter in this emotional story that gains heart-pounding suspense when the outside world intrudes.

Children's & Young Adult

The Door of No Return

by Kwame Alexander

In this foreboding yet mesmerizing historical novel in verse by Newbery Medalist Kwame Alexander (The Undefeated; The Crossover), Asante villager Kofi Offin comes face to face with the door of no return.

Eleven-year-old Kofi lives with his family in a Ghanaian village. He spends his time with friends Ebo and Ama and attending school, where he learns English, European history and Western values. As Kofi develops a crush on Ama, he realizes that his cousin is also smitten. Kofi decides he will prove that he is the better romantic interest by challenging his cousin to a race in the river Offin.

The river plays a huge role in Kofi's life. He was named after it and, though it is a place of happiness for him and his friends, villagers gossip that beasts dwell there at night. Kofi questions the gossip until he sees for himself that there truly are monstrous things hiding near the water--snares designed specifically to capture humans. The moment Kofi is caught, he is placed on a path that leads directly to the door of no return.

Alexander's descriptive language, moody tone and sometimes distressing scenes explore and expose Kofi's emotions, allowing readers to empathize and connect with him. The book unfolds predominantly in verse, which carries readers swiftly through this riveting work of historical fiction. Alexander masterfully displays Asante culture in Kofi's everyday life through games like oware, the cuisine, storytelling and the use of Twi, the native tongue. Copious backmatter includes a Twi glossary, author's note, legend for Adinkra symbols and a list of real locations used in the book. --Kharissa Kenner, children's librarian, Bank Street School for Children

Discover: An 11-year-old Ghanian boy must fight for his survival in this gut-wrenching historical novel in verse from Newbery Medalist Kwame Alexander.

Odder

by Katherine Applegate, illus. by Charles Santoso

In the delightful free verse novel Odder, Newbery Medalist Katherine Applegate (The One and Only Ivan) introduces a playful, inquisitive sea otter who lives off the coast of California.

Three years ago, the adorable Odder was separated from her mother during a sudden storm. The young marine mammal was rescued by the aquarists of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, nursed back to health and released into the wild. Fully grown Odder ("the queen of play") constantly looks for food and adventure. When she persuades cautious friend Kairi to swim out into the Bay, they encounter a great white shark. The shark wounds both otters before realizing that sharks don't even like otters as food. Odder is again found by aquarium staff and brought back to the artificial environment. Odder's second stay at the aquarium is very different from the first: she and Kairi will not be released, but they will help the scientists raise otter pups in new ways.

A humorous and somewhat aloof third-person narrator tells readers about Odder's first stay at the aquarium through flashbacks during her second stay. As the back story unfolds, readers learn a great deal about sea otters and the wise people who study them but try not to bond too closely. Applegate's text is absorbing, her spotlight on the animals' nature and emotions powerful. Odder "loves to roughhouse,/ can be pushy and eager,/ too unruly for some,/ but watching her/ work the water/ is a joy." Charles Santoso (Wombat Underground) sensitively details his realistic, curvilinear black-and-white illustrations. Santoso's superb spot art and the extensive author's note add much to this stellar presentation. --Melinda Greenblatt, freelance book reviewer

Discover: Animal lovers and anyone who appreciates a winsome protagonist should find Odder the otter's story compelling reading.

Curve and Flow: The Elegant Vision of L.A. Architect Paul R. Williams

by Andrea J. Loney, illus. by Keith Mallett

Curve and Flow tells the inspiring story of Paul R. Williams, a gifted architect who worked hard to achieve success despite early 20th-century racism in the U.S.

Los Angeles-born Paul "loves to draw and draw--especially buildings!" As a boy who dreams of designing his own home someday, he delights in the "swooping lines of L.A. [that] curve and flow around him." Unfortunately, the "big stone wall of racism" blocks his path. But Paul "loves a challenge," and even though no one has "ever heard of a Negro architect," he's determined to "take a curve and flow around" the problem. He studies, hones his skills and wins contest after contest with his clean and clever designs. He's hired by a top architectural firm in L.A., then starts his own business. Paul designs "bold, dazzling, innovative, and unforgettable" homes--houses he's not allowed to live in because "a huge invisible wall of laws... blocks Black people from living in many parts of Los Angeles." But he never stops believing he'll design his own home, never stops working, planning, building, curving and flowing until he makes his dream come true.

Andrea J. Loney's (Double Bass Blues) lyrical approach and recurring metaphors allow her to relate Williams's story deftly and with a gentle hand. Her back matter contains an extensive timeline that grounds and expands her focused text. Keith Mallett's (Sing a Song) detailed digital illustrations--including stunning endpapers--give a strong sense of the era; blues, browns and yellows lend an appropriately old-timey feel. Curve and Flow delivers an accomplished and uplifting biography of a Black man who "created more than 3,000 structures around the world" and is integral to the history of Los Angeles. --Lynn Becker, reviewer, blogger and children's book author

Discover: Curve and Flow takes an inspired look at Paul R. Williams, a gifted architect who achieved success despite the ugly realities of early 20th-century racism in the United States.

Standing in the Need of Prayer: A Modern Retelling of the Classic Spiritual

by Carole Boston Weatherford, illus. by Frank Morrison

Standing in the Need of Prayer is a love letter to the Black community from Coretta Scott King Award-winners Carole Boston Weatherford (Unspeakable) and Frank Morrison (R-E-S-P-E-C-T). The dignified text and glorious oil and spray paint illustrations acknowledge key historic moments and figures in Black history.

Weatherford's reworking of the lyrics to this "African American spiritual" brings readers on a symbolic pilgrimage through Black history. Morrison's magnetic art first depicts slender, scarred Black bodies in bondage: "It's me, it's me, O Lord,/ Standing in the need of prayer." This is followed by Nat Turner's rebellion against enslavers--"It's a preacher with a scar like a lightning bolt,/ Standing in the need of prayer." Ruby Bridges holds school books while white people angrily protest ("It's the first Black students walking into/ all-white classes"); Martin Luther King Jr. gestures at a church podium, the audience lifting their hands in praise ("It's orators, whose daring words/ move the masses"). Each line and accompanying illustration build a picture of Black resilience.

Weatherford and Morrison's picture book makes it clear that the fight for justice for Black lives is not yet over. Morrison's final spread features two young people. One wears a hoodie stating "Justice," the other leans over a graffitied wall that includes "their names" and "BLM." The book ends with contemporary events of ever-expanding Black history: "It's me, it's me, O Lord,/ Standing in the need of prayer." The book is a lesson, a tribute and an inspiration that should work as both an excellent read-aloud and potential sing-along. --Kharissa Kenner, children's librarian, Bank Street School for Children

Discover: Two Coretta Scott King Award-winners craft a motivational and uplifting retelling of Black history using the popular African American spiritual "Standing in the Need of Prayer."

Order of the Night Jay: The Forest Beckons

by Jonathan Schnapp

Frank, a bear, anxiously and unwillingly heads off to Camp Jay Bird in the first of Jonathan Schnapp's debut graphic novel series, Order of the Night Jay. The charming, purposefully educational adventure pits Frank and his new friend Ricky, a raccoon, against a pair of bully third-year scouts as they try to uncover the secrets of a mysterious cave.

Frank, the only large animal at camp, is an outcast from arrival. But Ricky doesn't seem to mind that Frank is a bear. Ricky is a risk-taker, a talker and a go-getter who ropes a protesting Frank into friendship and adventure. The head counselor, a squirrel in an oversized hat and glasses named Big Edna, acts as the camp's moral compass by regularly spouting maxims at her charges. When the other campers complain about Frank's presence, she simply admonishes them, "Just because he looks different on the outside doesn't mean he's bad on the inside." Unfortunately, a couple of campers ignore Big Edna's words and send Frank and Ricky on a wild goose chase in the woods. As Frank and Ricky wander lost, they find a scary cave and discover that it holds secrets.

Schnapp works science into the art by creating realistic images of the outdoor setting: eastern white pine, fungus, erosion. A plot twist involving the use of magnets and a compass sneaks in another STEM element. The Forest Beckons is a cute beginning to this graphic series. The lessons of fairness, inclusivity and friendship are easily understood as depicted by the likable cast of woodland characters. Young graphic novel readers are sure to find the adventure engrossing. --Jen Forbus, freelancer

Discover: Woodland creatures at a summer camp venture into a mysterious cave in the first installment of a graphic novel series that embraces the value of friendship and importance of acceptance.

In the Media

The Writer's Life

Reading with... Jonathan Escoffery

|

|

| photo: Cola Greenhill-Casados | |

Jonathan Escoffery is the recipient of the 2020 Plimpton Prize for Fiction, the 2020 ASME Award for Fiction and a 2020 National Endowment for the Arts Literature fellowship. His writing has appeared in Oprah Daily, the Paris Review, American Short Fiction, Electric Literature and Zyzzyva, and has been anthologized in The Best American Magazine Writing 2020 and elsewhere. Escoffery is a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and resides in Oakland, Calif. If I Survive You (MCD/Farrar, Straus & Giroux, September 6, 2022) is his debut story collection and follows a Jamaican family striving for more in Miami.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

Our hyper-observant Jamaican American hero, Trelawny, stumbles into homelessness, pseudo-sex work and the impermeable boundaries of Blackness in his tragi-comedic quest to be loved.

On your nightstand now:

I've mostly been reading debuts this year--up next is Cleyvis Natera's novel Neruda in the Park, Nishant Batsha's Mother Ocean Father Nation and Putsata Reang's Ma and Me.

Favorite book when you were a child:

It might have been Goblins in the Castle by Bruce Coville because I loved the idea of being orphaned (sorry, Mom and Dad) in a castle and setting off toward adventure through a hidden passageway I discover in my bedroom. Retrospectively, I like that it provides witty criticism of both xenophobia and our prison system.

Your top five authors:

Impossible, but let's say:

Zora Neale Hurston for capturing the inner workings of Black humor.

Nella Larsen for her unflinching portrayal of Black identities and their treatment across various geographical locations.

Langston Hughes for everything he ever wrote, starting with "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain," which shifted my worldview and my approach to writing fiction.

Kurt Vonnegut for bridging humor and inventiveness by engaging with humanity's many shortcomings.

Denis Johnson for some of the cleanest, most surprising prose ever.

Book you've faked reading:

I've faked so many books. It's usually by accident. I'll be at a cocktail party--a red Solo cup affair, more likely--and I'll be too tall to hear what anyone is saying. Tall people have a terrible time at these things--the chatter is always chest or navel level. And I'll think you mentioned this book when you really said that book with a similar title and by the time I recognize my misstep it's too late to restart the conversation because maybe we connected over our mutual love of that book I now realize I know nothing about and suddenly it's six months later and we're in a relationship and I still haven't read it because what if you have terrible taste?

I also faked Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter in college. The prose was painful, and I figured I gleaned enough from the title to write a paper on it.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Johann Hari's Stolen Focus. I proselytized about this book for a solid three months after listening to the audiobook. I lost friends.

It's about all the entities conspiring to not only steal our focus but ruin our individual and collective ability to think. These entities include predatory algorithms deployed by social media companies and the makers of smart devices and mid-20th-century changes to the way we eat and the way we educate our children.

Book you've bought for the cover:

My books are the only art I own, so I'm especially moved by beautiful book covers. Maurice Carlos Ruffin's We Cast a Shadow has a perfect cover (particularly the silver U.S. hardcover), as does Paul Beatty's The Sellout (one of my favorite novels all around), as does Alan Heathcock's new novel, 40. I couldn't leave Marcus Books the other day without Popisho by Leone Ross because of its gorgeous cover.

Book you hid from your parents:

I never hid books from my parents, but had I been asked about what I was reading, I might have omitted all the sex, violence and sexual violence in Brian Stableford's vampire epic, The Empire of Fear, which I read when I was 12.

Book that changed your life:

The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. My God, the genius in this book! Reading it opened my eyes to the long-running conversation Black writers in America have been holding about the state of Black America and the African diaspora.

Favorite line from a book:

The only line from literature that I can remember off the top of my head that hasn't transcended to cliché is from Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita. "You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style." Mostly I remember people in my MFA repeating it over and over, but I like the idea that a writer's "prose style" can tell you about their values, morals, proclivities and so on.

Five books you'll never part with:

Justin Torres's We the Animals because it's probably the most beautiful, musical prose I've ever read.

Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son because on top of the gorgeous prose, Fuckhead is one of the most enjoyable characters ever created because his drug-induced worldview is so tender and cruel and funny as all hell.

Nella Larsen's Quicksand because I hate that I live in a world where this novel continues to be overlooked and undervalued. I suspect that it tells too much truth about the experience of mixed Black American womanhood to ever get its shine.

Writers may be familiar with this adage: books aren't finished, they're abandoned (by their creators). I believe this is true, except in the case of Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude. That novel was cooked to perfection.

Finally, for their humor, creativity and empathetic renderings, I'd say Vonnegut's Cat's Cradle or Slaughterhouse-Five, but I keep lending these novels out and I never get them back. If you're reading this, I want my books back.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Percival Everett's I Am Not Sidney Poitier is the most outrageously hilarious book I've ever read. I'd love to embarrass myself laughing my head off in public like I did the first time around.

Book Candy

Book Candy

"What do we really know about the history of the printing press?" Atlas Obscura asked.

Open Culture herded up some "cats in medieval manuscripts & paintings."

Cartoonist Tom Gauld "on the library's new cataloguing system" for the Guardian.

Mental Floss recalled "when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle opened a psychic bookstore."

Hester

by Laurie Lico Albanese

A magnificently crafted 19th-century drama shimmering with enchantments, Hester by Laurie Lico Albanese is the story of a beautiful, talented Scottish needleworker, Isobel Gamble, and her love affair with dashing New Englander Nathanial Hawthorne at the cusp of his distinguished writing career. With the affair and its turbulent aftermath at its literary core, Albanese's sumptuous third novel sets sail from Scotland to Salem, Mass., and beyond on a grand historical adventure, exploring the lingering legacy of witchcraft trials and the struggles of immigrants, including freed slaves, to make a home in the New World.

Isobel narrates, first as a child growing up in the idyllic Scottish countryside and then as a young woman trying to build a new life in Salem. Hester takes root and blossoms around an intriguing, irresistible premise: it imagines the romance between Isobel and Nat--as Hawthorne was known in his hometown--as the inspiration for The Scarlet Letter and Isobel as Hawthorne's muse for his famously tragic heroine Hester Prynne. Isobel's account, she offers, is "the true story of how he found his scarlet letter--and then made it larger than life."

In early 1829, 19-year-old Isobel and her apothecary husband, Edward, leave Scotland under a cloud of financial scandal. They cross the Atlantic on a commercial ship bound for Salem, commanded by Captain William Darling. In Darling she surprisingly finds a fellow needleworker and a dependable friend. Determined and ambitious, Isobel hopes to earn enough money to open her own dressmaking shop and become financially independent from her thieving, opium-addicted husband (who soon departs Salem on another ship, purporting to be a medic). Sentimentality for the family she left behind is a luxury Isobel cannot afford, although she allows herself to daydream about the mythical selkies and faeries of her childhood.

In the bustling port city of Salem, she meets Nat, a tall, caped man in his mid-20s with a limp, who's struggling to make a name for himself as a writer. Nat's family has lived in Salem for generations; this affords him a level of security and acceptance not extended to newcomers like Isobel. Her new neighbors, Zeke, Mercy and Mercy's children, Ivy and Abraham, are kind but secretive, and she forms few friendships.

Albanese resurrects historical figures who contributed to the town's vibrant African American population, including John and Nancy Remond, a couple who created a legacy of hospitality and social activism. Isobel suspects that Zeke and Mercy, who are Black, are collaborating with the Remonds--hiding something--but the sheer scale of their clandestine activities comes into focus only after the drama of Hester reaches a fever pitch and Isobel's true destiny is unveiled.

Albanese captures the busy prosperity and rituals of Salem families: shopping on market day at the wharf, attending church on Sundays. She incorporates the disquieting Puritan undertones from the town's dark past as an epicenter of the witchcraft trials in the 1690s, a heritage that weighs heavily on Salem's inhabitants. Nat's forefathers were responsible for the hangings of many condemned women, and their shameful family history is a burden Nat deploys to fuel his tortured writing.

Any mention of witchcraft terrifies Isobel. Her namesake ancestor, Isobel Gowdie, a historical figure of some fame, was accused of being a witch in 1660s Scotland. Isobel worries about her own proclivity to magic, having inherited unusual sensory traits that enhance the sounds she hears with colors and textures, like the rich, elderberry fruit of Mercy's speech or the soft, slippery melon pink and green of Ivy's voice. Each letter of the alphabet appears to her in a particular hue, with the letter "A" a vibrant scarlet color. An aura of enchantment trails Isobel, from her fiery red hair to the bewitching artistry of her embroidery, her work coveted by society ladies. She keeps her gifts secret, concerned about associations with witchery.

Albanese's elegant writing captures the dynamic, sensual energy between Isobel and Nat in breathtaking detail. Nat's seduction of Isobel is driven by an urgent and compelling need to practice his storytelling craft, so much so that he credits Isobel's very appearance in Salem to his own burning imagination. Isobel is captivated by Nat's ability to openly indulge in a world of fantasy so different from the dull churn of her isolated existence. The calm, rhythmic act of sewing is her salvation; it consumes her and also puts food on the table, and her artistic gifts are part of her allure for Nat. Isobel uses her needle to tell her own stories and discovers in Nat a soul mate she can confide in.

As their relationship intensifies, Isobel's carefully cultivated reputation in Salem society is at risk of being destroyed by the scandal of their affair. In the life path she ultimately chooses, Isobel's raw power flows from her refusal to internalize the shame others attempt to foist upon her, embracing the ideals of self-determination and courage that propelled Hester Prynne to literary feminist fame. In Hester, Albanese has masterminded a thoroughly immersive drama and a memorable, spirited heroine for the ages. Isobel's appeal crosses cultural and generational borders to embody a timeless existential quest for the freedom to love and live as one pleases. --Shahina Piyarali

An Iconic Heroine Has Her Say

An Interview With Laurie Lico Albanese

|

|

| (photo: Martha Hines) | |

Laurie Lico Albanese is the author of Blue Suburbia: Almost a Memoir; and the novels Lynelle by the Sea; The Miracles of Prato, co-written with art historian Laura Morowitz; and Stolen Beauty. Albanese has worked in book publishing and journalism; her travel and general-interest articles have appeared in the New York Times and elsewhere. She has taught creative and formal writing to all ages, and lives with her husband in Montclair, N.J. Albanese's fifth book, Hester (St. Martin's Press, October 4, 2022), is inspired by the heroine of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter.

What was it about The Scarlet Letter and the character of Hester that made you want to tell her story?

Hester Prynne is an iconic heroine, but like Helen of Troy, she has very little to say for herself. Who was she? What would she want us to know about how she came to be the star of Hawthorne's tale? What sorts of decisions and turning points led her to become a ferocious single mother who still inspires us today?

Readers and scholars continue to debate whether Hester is an empowered proto-feminist, or a polemic figure meant to warn women away from passion. I decided I'd let Hester speak for herself, and started out by simply asking: Who are you?

Nathaniel Hawthorne is portrayed in exquisite detail, including the suffering he endures in the pursuit of his art. What drew you to his character?

Nat is a writer, and I identified with him as a young artist struggling to make his way in the world. Writers need grit and a certain hubris, but also a deep vulnerability. It wasn't hard for me to give these attributes to Hawthorne.

I made him the sort of handsome, brooding narcissist that a vulnerable young woman might fall for. Narcissists wound, yet they feel wounded by others and see themselves as victims. This is the narcissist's dilemma as I understand it, and I wanted to explore that on the page. Nat pursues what he wants, without worrying about how his actions might hurt others. Later, he uses his pain for inspiration.

Must readers be familiar with The Scarlet Letter to enjoy Hester?

Hester is a coming-of-age story about a creative young woman whose gift is a curse that is also a lifeline, once she can see it that way. I don't think you have to be familiar with The Scarlet Letter to appreciate Isobel Gamble's struggles, fears or desires.

This is also a love story, and I kept thinking about Heathcliff while I was writing it--also, Mr. Darcy. You don't need to know the original stories to recognize the brooding hero archetype or to feel fascinated as he advances toward our heroine. Is she powerless, or powerful? Does she know how to harness and use her strength?

It's my hope that the two books complement one another.

Would you classify Hester as a romance novel in the way Hawthorne described The Scarlet Letter?

Hawthorne defines "a romance" as a story that reaches beyond what is probable, into a world that is fantastical. "Romance" didn't mean love story, but simply something improbable. I find Hester entirely plausible so, no, it is not "a romance."

In his preface to The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne says his story takes place "somewhere between the real world and the fairy-land, where the Actual and the Imaginary may meet...." I place my own story squarely in that space, with a firm footing in the Scottish myths of Isobel's childhood.

You write expansively about questions concerning witchcraft and enchantment in the novel. What did you hope to achieve by telling this history from both Isobel's and Hawthorne's family perspectives?

Anyone who lives a creative life is inviting enchantment into their days. How is that summoned, where is it found in our culture and where is it stifled? How is it enriching, and how does it interfere? This is one way I considered the question of enchantment in Isobel's and Nat's stories.

The other was to make them descended from the accused and the accuser in the historical record of "witches." In Salem, descendants of the accused and the accusers in the 1692 witch trials live side by side to this day. Who forgives, and who doesn't? What is the cost? I wanted to let that play out in the story from all angles.

As a recent immigrant, Isobel struggles to gain acceptance in her new home. What is it about the people and history of Salem that makes it hostile to outsiders? Is Hawthorne representative of that hostility?

Although Salem was a wealthy international shipping port in the early 19th century, it was a society closed to outsiders. Hawthorne's ancestor William Hathorne crossed the Atlantic in 1630 aboard the Arabella and was granted land by the Massachusetts Bay Colony under the charter of King Charles. Those descended of Salem's first families were committed to holding onto the wealth and property they'd claimed and fought for.

As a descendant of an original colonist, Hawthorne is a Salem insider. But he's also an outsider because his family has lost their standing and their wealth--his father died when he was four, leaving his mother impoverished. His duality intrigues me, much as it plagued him.

The creative process is an essential element in the love story between Nat and Isobel. Why was that important to you?

Creative tension can be a lot like sexual tension, in that friction is the place where the spark is made. I tried to put that fission into all of their interactions. For Isobel to be more than a muse to Hawthorne, I had to make him her muse, as well. Their flirtatious banter around writing and embroidery is a form of seduction and foreplay. My favorite part of their romance is the way they inspire and embolden one another to greater and more ambitious work.

As a self-described extrovert, how do you mitigate the solitary nature of your craft?

I keep a regular work schedule, stay in close touch with friends and family, play sports and try to get out in nature every day. Nothing mysterious there--in the time of Covid, most of us have found it takes effort to maintain the sustenance of community. I'm extremely thankful to live in a town that has a rich writing community, and to have dear friends who are novelists, journalists, scholars and artists. People matter to me. My husband is in publishing, and we have a wonderful, shared life. Our grown children are big readers, too.

What do you most hope for Hester as you release this story into the world?

I hope readers will embrace this story as a continuation of the conversation Hawthorne began in 1850, when he claimed The Scarlet Letter was inspired by a piece of worn embroidery that he'd unearthed behind a brick in the Salem Custom House.

The Scarlet Letter takes place in 1600s Boston and was published in 1850. Likewise, Hester takes place roughly 200 years in our past. Hester is historical fiction inspired by historical fiction; it's a reconsidering of the tale as a woman's story of empowerment and agency. I think it's time that Hester had her say. --Shahina Piyarali

Rediscover

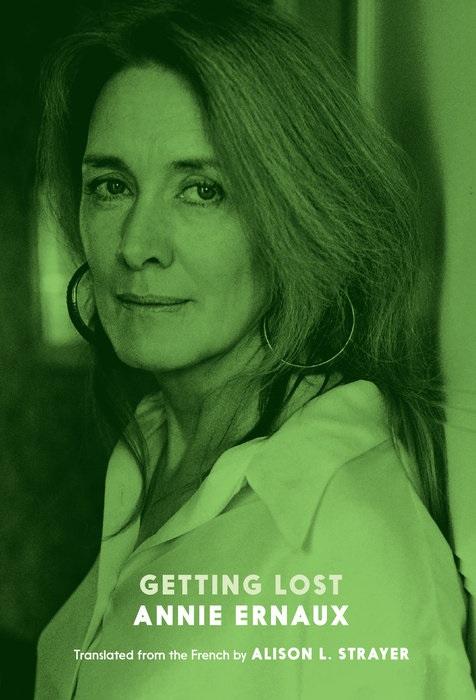

Rediscover: Annie Ernaux

French writer Annie Ernaux has won the Nobel Prize for Literature. At a news conference this morning announcing the win, the Swedish Academy cited her for "the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory." The author of more than 20 works, mainly fiction, Ernaux is best known for her memoir The Years, published in a translation by Alison L. Strayer by Seven Stories Press. The translation was shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize, and received the 31st Annual French-American Translation Prize for nonfiction and the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation.

French writer Annie Ernaux has won the Nobel Prize for Literature. At a news conference this morning announcing the win, the Swedish Academy cited her for "the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory." The author of more than 20 works, mainly fiction, Ernaux is best known for her memoir The Years, published in a translation by Alison L. Strayer by Seven Stories Press. The translation was shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize, and received the 31st Annual French-American Translation Prize for nonfiction and the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation.

Getting Lost, a diary of the affair she had with a younger, married Soviet diplomat, also translated by Strayer, was published by Seven Stories just days ago. The affair was also the basis for her novel Simple Passion. Seven Stories has published other titles by Ernaux, including A Girl's Story, A Woman's Story, Getting Lost and Shame. Seven Stories publisher Dan Simon described Ernaux to the New York Times as someone who "stood up for herself as a woman, as someone who came from the French working class, unbowed, for decade after decade." He also said the Nobel committee had made "a brave choice by choosing someone who writes unabashedly about her sexual life, about women's rights and her experience and sensibility as a woman--and for whom writing is life itself."

French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted: "Annie Ernaux has been writing for 50 years the novel of the collective and intimate memory of our country. Her voice is that of women's freedom, and the century's forgotten ones."

Yale University Press is planning to publish Ernaux's Look at the Lights, My Love in 2023. Her work has also been adapted into films, including Happening (2021) and Simple Passion (2020). The Nobel Literature Prize awards ceremony will take place in Stockholm on December 10.