Friday, December 9, 2022

Among the 25 books reviewed this week: Fatty, Fatty, Boom Boom, Rabia Chaudry's "touchingly warm and intimate" memoir in which "fragrant, delectable homemade Pakistani dishes" feature; Requiem for the Massacre, in which sportswriter and longtime Tulsan RJ Young's "clear-eyed, first-person narration blazes from the page" as he examines the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre; and Newbery Honor author Jasmine Warga's A Rover's Story, which "thoughtfully balances the technical aspects of this STEM story with social-emotional nuance." Plus so much more!

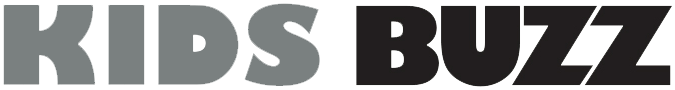

In The Writer's Life, Brandon Sanderson discusses his Hugo Award-winning novella The Emperor's Soul on its 10th anniversary and its continuing relevance--he believes that today "we make less of an effort than we ever have to understand each other...."

At Certain Points We Touch

by Lauren John Joseph

Lauren John Joseph is extraordinarily talented on many fronts. At Certain Points We Touch, their first proper novel (after the experimental work Everything Must Go), distills those talents into a queer, autofictional love story both haunting and hilarious, and crystallizes Joseph as a literary artist of the highest caliber.

The exceedingly eloquent narrator, JJ, was born to be a storyteller, but whether that dream is waylaid or fostered by their impulsivity is anyone's guess. JJ bounces from London to San Francisco to New York City to Mexico City, couch-surfing in friends' apartments and wig-swapping their way through gay nightclubs and art galleries. If there is one constant in JJ's eclectic adulthood, it is Thomas James, "a disco Lothario," a sulky bad boy, the man who forever captured JJ's heart.

Thomas James is a cool customer, aloof and brooding. He is skeptical of queer labels in general, and he is critical of JJ's progressive politics. He bears every red flag like a badge of honor, both infuriating and enchanting his lover. Yet despite their crossed stars, JJ and Thomas James enjoy an explosive sexual connection that infuses every scintillating line of this exceptional novel.

At Certain Points We Touch ruminates on themes of love, loss and queerness with such a mature sense of craft that one can almost hear the scratch of a calligrapher's stylus as they painstakingly etch this elegy to a dead lover. Born out of passion and grief, the novel aches to be the last word on the untimely death of Thomas James, and the emptiness he left in JJ's soul. Lauren John Joseph has produced a masterpiece. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

Discover: An ornate elegy to a dead love, this funny, sexy and smart first novel displays Lauren John Joseph's many talents.

Foster

by Claire Keegan

Foster by Irish writer Claire Keegan (Antarctica) is a slim novel that resonates with emotional depth. It is the story of a young girl in rural Ireland, sent to stay with relatives for a summer. This edition of Foster, winner of the prestigious Davy Byrnes Award when it was published in 2010, is the novel's first publication in the U.S. It follows the success of Keegan's Small Things Like These, which was shortlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize, the shortest novel ever nominated.

One of many children of a father who drinks "a liquid supper" and a mother "hard with the next baby," the unnamed protagonist describes her Da delivering her to the Kinsella farm, leaving "without so much as a good-bye, without ever mentioning that he would come back for me." His parting words are: "I hope this girl will give no trouble." She recognizes she's in a remarkably different home: "Here there is room, and time to think." The Kinsellas are also different. Mrs. Kinsella stresses she won't be working and washes the girl in water "deeper and hotter than any I have ever bathed in"; the girl notes that the woman's hands are "something I have never felt before and have no name for." Secure in this pastoral life, the girl, whom Kinsella affectionately calls "petal," thrives--all the while dreading the end of her time there.

Keegan's spare prose conveys both love and sorrow. The novel's apparent simplicity belies its poetic exploration of childhood heartbreak, loss and love. Though the ending is ambiguous, there is no doubt the Kinsellas and the girl are forever linked by the joy of their shared summer. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

Discover: This spare novel, acclaimed in the author's native Ireland, is the poignant story of a girl whose summer spent with relatives introduces her to a loving, happy home.

This Time, That Place: Selected Stories

by Clark Blaise

The work of Canadian American writer and teacher Clark Blaise isn't widely known outside the world of those who regularly consume short fiction in literary magazines. But now, with the publication of This Time, That Place: Selected Stories, a collection of 24 stories drawn from some 50 years of his writing, readers have a fresh opportunity to encounter the work of a writer whose literary talent is evident in every one of these well-crafted tales.

Born in 1940 in North Dakota to Canadian parents, Blaise spent his childhood and adolescence in nearly constant movement. That peripatetic existence is reflected in the variety of settings for these stories, encompassing some of the places where his family landed, including steamy and openly racist rural Central Florida in the 1940s ("Broward Dowdy" and the slyly comic "The Fabulous Eddie Brewster") and Pittsburgh in the 1950s ("Grids and Doglegs," the charming story of a high school nerd's memorable prom date with the girl of his dreams).

Not surprisingly, a sense of displacement and rootlessness haunts many of his protagonists. Blaise treats that subject most directly in a trio of stories involving the character Phil Porter--his name while living in Pittsburgh--but who becomes Philippe Carrier when his family must flee back to his Montreal birthplace after his father assaults a fellow employee.

Blaise's stories are shapely and full of keenly observed details that bring their often unglamorous settings to life. For those unfamiliar with his work, This Time, That Place will come as an especially pleasant discovery. --Harvey Freedenberg, freelance reviewer

Discover: Veteran writer Clark Blaise offers a diverse selection of 24 well-crafted short stories in this career-spanning collection.

Now Is Not the Time to Panic

by Kevin Wilson

Art can lead to unintended consequences, as two teenagers discover in the witty Now Is Not the Time to Panic by Kevin Wilson (Nothing to See Here; Baby, You're Gonna Be Mine; The Family Fang). In 1996, bored Frankie Budge, a native of Coalfield, Tenn., who spends her time working on a "weird girl detective novel," meets aspiring artist Zeke, a wealthy Memphis teen, at the town pool. Frankie and Zeke create a poster featuring Zeke's edgy art and the phrase "The edge is a shantytown filled with gold seekers, we are the new fugitives, and the law is skinny with hunger for us." Using a copier Frankie's triplet brothers stole from the high school, they reproduce and display it all over town. The poster creates a national frenzy, the media asking if it's the work of the devil. No one knows who made it, but in 2017, a New Yorker art critic, certain that it was Frankie, who is now an author of novels for young readers, tracks her down for a story that will reveal the secret Frankie longs to keep.

Wilson presents a layered work that incorporates many themes into its deceptively simple story, including the ways in which works of art can be easily misinterpreted and the hysteria that sometimes passes for news reporting. "If you love something," Frankie's mom tells her, "you can't think too much about what went into making it or the circumstances around it." As this novel illuminates, art can be transformative--but who and what it transforms are unpredictable. --Michael Magras, freelance book reviewer

Discover: Two teenagers create a poster that becomes a national craze in this witty work about the perils and pleasures of art.

Someday, Maybe

by Onyi Nwabineli

A young woman struggles through anguish and depression after her husband dies by suicide in Someday, Maybe, the raw, honest first novel from Nigerian British author Onyi Nwabineli.

"Here are three things you should know about my husband," main character Eve tells readers, going on to say that she loved Quentin deeply, he seemed happy and yet, "he committed suicide." She says of herself, "Here is one thing you should know about me: 1. I found him. Bonus fact: No. I am not okay." The aftermath leaves her unable to do more than lie in bed and try to catch his scent from a sweatshirt. Her close-knit Nigerian-British family rallies around her with food, prayers and nudges to return to life, but grief consumes her as she tries to take stock of her new reality. A steady diet of prescription pills dulls the pain but ultimately sends Eve into a deeper spiral that ends in the loss of her job. Complicating matters further is Aspen, Quentin's mother, who always disapproved of Eve as a daughter-in-law and now blames her for Quentin's death. As Eve freefalls into despair, a surprising revelation upends her world yet again, driving her briefly to flee in search of the answers behind Quentin's actions.

Nwabineli's perceptive, painstaking interrogation of loss and depression is told in Eve's candid, sarcastic voice. Her grief is portrayed realistically, as a complex, long-lived creature that embeds itself deeply, shifting but always present. Readers ready for a challenging pilgrimage through tragedy will find rewards in Nwabineli's clear-eyed, compassionate take on the often-unremarked messiness of survival. --Jaclyn Fulwood, blogger at Infinite Reads

Discover: Nwabineli's first novel is a clear-eyed, compassionate take on grief as a young widow struggles with depression following her husband's suicide.

Dr. No

by Percival Everett

The phenomenally talented and prolific Percival Everett (So Much Blue; Percival Everett by Virgil Russell) conducts a highwire act in Dr. No, balancing mathematical theory with deadpan humor over a daunting crevasse of nothing. Fortunately for readers, narrator Wala Kitu is an expert on nothing. But unfortunately for Wala, his expertise attracts the dangerous criminal mastermind John Sill, who wishes to harness the power of nothing for a diabolical plan.

A distinguished professor of mathematics at Brown University, Wala doesn't have a villainous bone in his body. He, like his colleague Eigen Vector, is hopelessly literal and not especially street-smart. He keeps a one-legged bulldog as a companion, whom he calls "Trigo" on account of the three missing limbs; curiously, man and animal converse at great length in Wala's dreams, where Trigo serves as an uncouth voice of reason. "The importance of nothing is that it is the measure of that which is not nothing," Wala says by way of introducing his field of study. "I work very hard and wish I could say that I have nothing to show for it." Sill, on the other hand, is a suave billionaire who is not afraid of killing anyone who stands in his way.

Dr. No is riddled with irresistible wordplay, as again and again characters express their fascination with and desire for nothing. It is an adventure that can be appreciated on any of the numerous levels that Everett is working on. From the unassuming bumbling of a humble mathematician to the provocative consequences of unmitigated power, nothing is quite as enjoyable as Dr. No. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

Discover: An unassuming expert in nothing embarks on a wildly entertaining caper when he contracts with an aspiring supervillain on a quest for nothing.

A Christmas Memory

by Richard Paul Evans

In A Christmas Memory, Richard Paul Evans (The Christmas Promise; The Road Home), author of more than 40 novels, delivers an emotionally moving fictionalized story that pays homage to a man who made a profound impact on his early life. The story begins in Pasadena, Calif., in 1967 and centers on Rick, a sensitive and bright, yet socially awkward, eight-year-old with Tourette syndrome. When Rick's older brother, Mark, dies in the Vietnam War, his death drives a wedge between his parents. The loss is compounded by the fact that Mark "didn't believe in war and didn't want to go." As the family struggles with grief and guilt, Rick's father loses his job. This forces a move to Salt Lake City, Utah, where Rick's mother was born and raised. Rick's parents separate shortly after the family settles into the house of Rick's deceased grandmother. While his mother sinks into a severe depression, Rick is bullied by peers and badgered by an ogre of a teacher. Rick finds respite when he befriends a neighbor's dog and, ultimately, the dog's elderly owner, Mr. Foster. This man of integrity--a Black contemporary of Rick's grandmother, separated from his own family--opens his house and heart to the young boy. He offers companionship and wisdom that shepherds Rick through a sad uncertainty, all of which coalesces into a touching and memorable Christmas.

Themes of friendship and forgiveness infuse Evans's beautiful and tender story, one that delivers a heartfelt message about remembrance, love and hope.--Kathleen Gerard, blogger at Reading Between the Lines

Discover: A profoundly tender, multigenerational story about a friendship that liberates a grief-stricken eight-year-old during Christmas in 1967.

Case Study

by Graeme Macrae Burnet

A psychological drama blurring the lines between fiction and reality, Case Study by Scottish author Graeme Macrae Burnet (His Bloody Project) centers on a disturbed young woman in 1960s London and her interactions with her late sister's psychotherapist, a charismatic Northerner named Collins Braithwaite. Burnet's fourth novel is a cleverly crafted investigation of sanity and identity, set against the backdrop of social upheaval in London at the dawning of the "Angry Young Men" era.

Longlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize, Case Study begins by informing readers of Burnet's literary fascination with Braithwaite, "an enfant terrible of the so-called anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s," and shares chapters from his biography of the man as he rises to the peak of his profession despite a chaotic personal life. These chapters alternate with excerpts from a set of old notebooks narrated by an unnamed woman whose sister, Veronica, took her own life while she was Braithwaite's patient and who claims that Braithwaite is guilty of criminal malpractice in letting it happen.

While Braithwaite's biography is a fascinating character study of a brilliant mind flirting with disaster and debauchery, it is the young woman's notebooks that will mesmerize readers. Lacking the confidence to confront Braithwaite with her allegations, she creates an alter ego, an alluring femme fatale named Rebecca Smyth.

Burnet's deployment of multiple narrative structures, his finely tuned depiction of Braithwaite, and the fascinating revelations of the diarist result in an unforgettable story, one that will rattle readers long after its startling, disorientating ending. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Mystery & Thriller

The Resemblance

by Lauren Nossett

The fact that tales of hazing and womanizing cycle through The Resemblance, a thriller centered on a University of Georgia fraternity, will probably surprise no readers. But the daringly dark turn that Lauren Nossett's sturdy fiction debut takes toward the book's midpoint will likely come as a shock.

From the first, The Resemblance seems destined to assume the shape of something it ultimately isn't: a straight-ahead procedural. Homicide detective Marlitt Kaplan is visiting her mother, a German professor, in her office at UGA when a car fatally hits a student at an intersection on campus. Witnesses say the black BMW didn't slow down before the crash and fled the scene right after impact. But two peculiar details distinguish this accident from a typical hit-and-run: witnesses report that the BMW's driver was smiling and that he looked an awful lot like the victim.

The victim is UGA junior Jay Kemp, a member of Kappa Phi Omicron. Once Marlitt learns that Jay was a frat brother, she starts ticking off possible motives for the murder: "Revenge for hazing fits neatly at the top of my list, followed by stealing someone's girlfriend, and your run-of-the-mill brotherhood rivalry." But as Marlitt proceeds with interviewing members of Jay's fraternity, her initial, obvious theories crumble. If they hadn't, she wouldn't have had to endure the calamity that engulfs her about halfway into the book.

The Resemblance is an alluringly somber and satisfying thriller. While the book doesn't present a counterpoint to Marlitt's disdain for fraternities, it's also true that nothing that happens in The Resemblance would make good marketing copy for Greek life. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: This alluringly somber and satisfying debut thriller revolves around the on-campus murder of a University of Georgia fraternity brother.

Science Fiction & Fantasy

Legends & Lattes

by Travis Baldree

Professional audiobook narrator and game developer Travis Baldree initially self-published his "high fantasy and low stakes" first novel, Legends & Lattes, which became a social-media sensation. It stars an unlikely coffee shop owner as she vies for business, builds a supportive social circle and quests for the perfect hot drink.

Orc barbarian and career adventurer Viv is ready to hang up her broadsword and live out her dreams of opening a café serving the exotic gnomish beverage coffee. Her research leads her to the city of Thune and an abandoned livery building that will need considerable work to pass as a café. Viv faces the challenge, wanting "something she built up, rather than cut down," and launches the city's first coffee shop. Helping her out are carpenter Calamity the hob, café assistant Tandri the succubus and baking genius Thimble the rattkin. Little by little, the cafe begins to take off. The menu expands as Viv begins to form a customer base, but challenges arise when a local crime boss sends thugs to extort protection money, leaving Viv struggling to keep to her new nonviolent way of life. To make matters worse, Viv has a deep secret about the café's success, and someone from her old life has figured it out. She'll need to use all her wits and newfound connections to keep from losing everything she's built, including her growing relationship with Tandri.

Baldree's combination of humor, fantasy elements and gentle plot lends itself to a comforting story. Fans of Terry Pratchett's Discworld series, tabletop fantasy RPGs and unlikely heroes should find much to love in this charming outing. --Jaclyn Fulwood, blogger at Infinite Reads

Discover: Audiobook narrator Travis Baldree made social media waves with this cozy, gentle fantasy about a retired orc warrior who opens a coffee shop.

Graphic Books

Big Man and the Little Men

by Clifford Thompson

For Clifford Thompson (What It Is: Race, Family, and One Thinking Black Man's Blues), the graphic novel Big Man and the Little Men is a new frontier in terms of form. But it's also entirely of a piece with Thompson's previous books, which address thorny social issues with a counterintuitively gentle touch.

As Big Man and the Little Men begins, Metropolis magazine has invited April Wells--a Black, New York-based memoirist who has appeared on Oprah--to write about William Waters, the Democrats' white presumed nominee for president. April took the assignment fully aware that Waters, who has a wife, has been accused of sleeping with male staffers. (He denies it.) While April is on the campaign trail with Waters, she's contacted by one of his former female staffers, who says "there's something you need to know" about the candidate. April feels increasingly out of her depth as things get dicier. At one point she thinks, "Here's where it would help to have gone to journalism school. Why did they ask me to do this? And why did I say yes?"

Thompson's art has a straightforwardness that allows readers to practically see the gears turning in the characters' minds. Among the most potent images are wordless panels showing April in private moments: writing, pacing in her hotel room and so on. These illustrations reinforce the point that for all the political intrigue afoot, Big Man and the Little Men never ceases to be April's story--and it's the sort that lingers. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: In this potent graphic novel of political intrigue, a magazine hires a Black female memoirist to write about the Democrats' white, rumor-plagued presumed nominee for president.

Food & Wine

The Pasta Queen: A Just Gorgeous Cookbook

by Nadia Caterina Munno and Katie Parla

Nadia Caterina Munno draws on centuries of tradition from her pasta-making Italian forebears, not to mention her social media fame, in The Pasta Queen: A Just Gorgeous Cookbook. With more than 100 recipes plus lush, full-page photographs of Munno and her culinary creations, this debut cookbook will delight both home cooks and Munno's TikTok, Instagram and YouTube fans.

"Pasta is my love language," writes Munno, who cites stories from the southern Italian village of her ancestors, a place known for its pasta factories. After successful careers in England and Italy, Munno and her husband moved to Florida, where she devoted herself to cooking and sharing the "just-gorgeous recipes" of her heritage. The Pasta Queen's easy-to-follow recipes fall into five inspiring groups, including "Recipes for Comfort" and "Recipes to Impress." The "passion cooking" she devotes to "every stir... and every garnish" is reflected in her recipe names: "Goddess of Love," made with tortellini, a pasta shape allegedly inspired in ancient times by Venus's belly button, includes butter, heavy cream and prosciutto, all of which contribute to a "godlike cloak" for the pasta, and "The Snappy Harlot" relies on a Calabrian chili paste, which Munno describes as a "slightly hot aphrodisiac." Gluten- and dairy-free recipes don't exclude flavor and sensuousness, as in the "Vegan Lady of the Night" with its "heat of summer" ingredients--tomatoes, eggplant and capers.

"All you need is love--and a little pasta magic--to show your nearest and dearest how much you care," Munno emphasizes in a cookbook that's liberally infused with her zest for food and life. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

Discover: Social media's "Pasta Queen" shares more than 100 Italian recipes--and her passion for cooking--in a cookbook filled with vivid photographs.

Biography & Memoir

Fatty Fatty Boom Boom: A Memoir of Food, Fat, and Family

by Rabia Chaudry

Fragrant, delectable homemade Pakistani dishes are central to Rabia Chaudry's touchingly warm and intimate narrative in Fatty Fatty Boom Boom. A woman who grew up besieged by harmful comments about her weight and appearance, Chaudry is an uplifting storyteller, and her humor-laden anecdotes balance the underlying gravity of her story with grace and skill.

Born in Lahore, Pakistan, Chaudry moved with her parents to Northern Virginia when her veterinarian father was offered a job at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the 1970s. Misguided efforts to make their scrawny toddler look like her American counterparts included feeding her two bottles of half and half daily and letting her gnaw on frozen butter sticks. As an overweight girl with a dark complexion, Chaudry was constantly reminded of her "future unmarriageability" by an immigrant community preoccupied with their daughters' marriage prospects. She got married early, while in college, to an unsuitable boy in an effort to disprove the naysayers.

An advocate for Adnan Syed, the young man convicted of murdering his high school ex-girlfriend in 1999, Chaudry was an executive producer of an HBO documentary based on her book, Adnan's Story. Being in the media spotlight made her self-conscious about her weight and frustrated that she couldn't take control of her own body. Eventually, her path toward improved health and fitness and inner contentment, plagued with many false starts, came with the hard-won wisdom of someone accustomed to being criticized for her appearance. It turns out that, for Chaudry, wresting control of her own narrative from those eager to pass judgment ultimately opened the door to self-acceptance. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Discover: A Pakistani American lawyer struggling with her weight chronicles with humor and sensitivity her path toward inner contentment and shares recipes for chai, ghee and the Pakistani dishes she loves.

Transformer: A Story of Glitter, Glam Rock, and Loving Lou Reed

by Simon Doonan

Glam rock, which first sashayed onstage in the early 1970s, rebuked rock music's customary machismo, and no album did the job better than former Velvet Underground front man Lou Reed's second solo effort, 1972's Transformer. On the occasion of the record's 50th anniversary, the perceptive and consummately witty Simon Doonan (Beautiful People; Drag: The Complete Story) presents Transformer: A Story of Glitter, Glam Rock, and Loving Lou Reed, in which he asks the musical question, "How did Lou become the guy who decided to fill the LGBTQ+ void and skew an entire album toward me and my cohort?"

To answer the question, Doonan double-tracks his own story with that of Reed's trailblazing album. Doonan was born in England in 1952; after he came of age, he didn't fully see himself reflected in rock music until he encountered Transformer, whose "Walk on the Wild Side" was a veritable roll call of real-life challengers to heteronormativity. The song was just one of the album's salutes to gender noncompliance. Doonan reports that Reed explained his intentions with the record a few years later: "I thought it was dreary for gay people to have to listen to straight people's love songs."

Doonan's book builds to a song-by-song anatomization of Transformer. He's a fount of swashbuckling hyperbole, and hardly a sentence wouldn't work as a pull quote. Of "Andy's Chest," an homage to Warhol, friend and mentor to Reed, Doonan writes, "The subtext in the mood of this song is clear: Being groovy will not save you." But Lou Reed's Transformer might. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: The perceptive and consummately witty Simon Doonan toasts Lou Reed's Transformer on the occasion of the classic album's 50th anniversary.

History

Requiem for the Massacre: A Black History on the Conflict, Hope, and Fallout of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

by RJ Young

In 1921, white Tulsans burned the prosperous Black business district of Greenwood to the ground, based on shaky allegations against a young Black man. In his powerful second nonfiction book, Requiem for the Massacre, sportswriter and longtime Tulsan RJ Young (Let It Bang) investigates the century-long fallout from the massacre and calls his hometown to account for its consistent devaluing of Black lives. Young, drawing on eyewitness accounts and other historical resources, opens with a detailed recounting of the massacre itself. He dives deeply into the origins of the phrase "Black Wall Street," still a common moniker for Greenwood. Young also traces his experiences as a teenager, college student and sportswriting professional in Tulsa, a town that often ignores or blatantly antagonizes its Black residents. The book's second half chronicles Young's journey to events commemorating the centennial of the massacre, which take place during racial unrest catalyzed by George Floyd's murder and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Young's clear-eyed, first-person narration blazes from the page: he explores the deeply complicated reality of being a Black man who owns property in a city, state and country that has often tried to prevent just that. He ties the Greenwood massacre and Tulsa's racism to the broader legacy of anti-Blackness in the U.S. and asks pointed questions about reparations, honest commemoration and true apologies. Unsettling, fierce and necessary, Requiem for the Massacre is a vital primer on a slice of American history that has been hidden for too long. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Discover: In his powerful second nonfiction book, RJ Young combines historical accounts of the Tulsa Race Massacre with his complicated experiences as a Black Tulsan.

Psychology & Self-Help

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki: A Memoir

by Baek Sehee, transl. by Anton Hur

Baek Sehee ingeniously combines elements of memoir and self-help in her first book, I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, a bestseller in her native South Korea. She offers an intimate look into one patient's experience in therapy and her own analysis of and takeaways from those sessions.

Consumed by a desperate sense of emptiness she calls "a vague state of being not-fine and not-devastated at the same time," Sehee seeks the help of a psychiatrist, ultimately resulting in a diagnosis of dysthymia, or persistent depressive disorder. Sehee approaches this book with a sense of precision and detailed emotional accounting, not merely recalling her psychiatric sessions from memory, but transcribing her recordings of the sessions word for word across the pages of this book. She then adds her own analysis of each session, drawing in real-life examples of how some of what she learned in therapy showed up in life outside of the psychiatrist's office.

I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki remains faithful to real life all the way to the end, not offering a neatly packaged revelation in which Sehee finds meaning and purpose in her suffering. Instead, she concludes "not with answers but a wish": to love and be loved, to hurt less and live more, to find joy amidst the hardships. Everyone is just trying to be as okay as possible, after all--and seeing Sehee's processing of that in I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is sure to make readers feel a little less alone in their own attempts. --Kerry McHugh, freelance writer

Discover: This is an intimate and vulnerable account of one woman's experience in therapy and her attempts to find joy in living her life with depression.

Science

How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures

by Sabrina Imbler

In the opening pages of the stunning and thoughtful essay collection How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures, science journalist Sabrina Imbler recalls the first time they wrote about an octopus and how it made them think of their mother: "I discovered unexpected, surprising resonances that cracked open what I knew about the ocean and myself." Expanding on that first essay (included in this collection as "My Mother and the Starving Octopus"), How Far the Light Reaches continues that tradition, weaving together the oceanic and the human in thought-provoking reflections on queerness, race, family, love and identity along the way.

Recalling their senior thesis on whales in "How to Draw a Sperm Whale," Imbler notes the many ways "we shoehorn distinctions between ourselves and other animals, often harming both of us." This balance of science and memoir blends seamlessly across each essay in Imbler's collection. Little-known bits of trivia about sea creatures (Did you know that a mother octopus does not eat while protecting her eggs, slowly dying as they grow? Or that cuttlefish can not only change color but texture as part of their self-protection mechanism?) sit aside startlingly clear reflections on what it is to be Imbler, to be one's own self, to be human ("I do not want to feel resolved about myself.... I want to imagine how I am continuing to live"). Tender and candid, How Far the Light Reaches is a poignant invitation into the depths of ocean life and a call to consider what nature can reveal about the human condition from a brilliant and poetic writer. --Kerry McHugh, freelance reviewer

Discover: This tender and thoughtful essay collection draws parallels between oceanic life and what it means to be human as it explores queerness, race, family, love and identity.

Travel Literature

A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast

by Dorthe Nors, transl. by Caroline Waight

For readers whose knowledge of Denmark is confined to Copenhagen and its environs, Danish writer Dorthe Nors's A Line in the World will come as a revelation. In 14 eloquent, observant essays that combine journalism, nature writing and memoir, Nors paints a vivid portrait of a remote and rugged territory whose striking scenery masks more than its share of dangers.

Though the essays describe a year of episodic travels, Nors (Mirror, Shoulder, Signal; Karate Chop) forgoes a strict chronology. Instead, from the Wadden Sea in the south to Skagen at its northern tip, she hopscotches along the 600 miles of what she calls "one of the world's most dangerous coastlines," at the western edge of the peninsula known as Jutland, where she grew up and lives today.

Nors's interests range widely, encompassing history, religion, sociology, culture and an assortment of scientific disciplines. In "The Timeless," for example, her description of the day she and her artist friend Signe Parkins, whose drawings enhance the book, spent viewing rural church frescoes, she touches on the status of women in traditional Danish society, and describes how her mother's youthful dreams of pursuing an artistic career were frustrated and only realized, in part, in adulthood.

Nors's prose, translated from the Danish by Caroline Waight, is both economical and expressive. When she's writing about nature she has a pleasing knack for engaging all the senses, and when she turns to some aspect of her family history, her candor is seasoned with a pinch of Scandinavian reserve. A Line in the World will appeal to a wide audience of discerning and curious readers. ---Harvey Freedenberg, freelance reviewer

Discover: In a collection of 14 precisely observed essays, Danish writer Dorthe Nors surveys the history, geography and culture of Denmark's western coast.

Art & Photography

Art Is Life: Icons and Iconoclasts, Visionaries and Vigilantes, and Flashes of Hope in the Night

by Jerry Saltz

Pulitzer Prize-winner Jerry Saltz (How to Be an Artist), senior art critic for New York magazine, likes to speak in superlatives. Jeff Koons's Puppy is "the greatest control-freak sculpture ever created." Jasper Johns's Flag is "the most iconic, transgressive object/amulet in late-twentieth-century American art." Here's one about Saltz, inspired by the caliber of his writing and observations in Art Is Life: he's the best art critic working today.

The book's 80-odd essays span 1999 to 2021. Surely two decades of rigorous engagement with art should guarantee an abundance of insight from any critic, but there's no one quite like Saltz. There are his whammo openers ("Two weeks ago, the Death Star that has hovered over the art world for the last two years finally fired its lasers"). There's his peppery-salty wit ("For nearly ten years, starting in the late nineties, art and money had sex in public. Lots of it. And really publicly"). There are his cross-genre comparisons placing fine art in a larger--some purists would say cruder--cultural context ("Hopper is the Leonard Cohen, Roy Orbison, and Bruce Springsteen of painting, an only-the-lonely artist of ordinary life").

Saltz's most rebellious act may be his determination to write accessibly in a field that tends toward easily satirizable impenetrability. His approach has always been fuss-free: as he writes of starting out as a critic, "I knew I wanted to write about art that I was seeing in the present and didn't want to have to read all those books that all those critics were always referencing." Who needs "all those books" now that there's Art Is Life? --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: Art Is Life presents two decades of rigorous engagement with art by sui generis Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Jerry Saltz.

Poetry

The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On

by Franny Choi

Every poem in Franny Choi's The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On has a line--or a few--where readers realize that, yes, this poem is for them. Her third collection is filled with such moments, lines that sing out, grabbing readers by the throat--or by the hand--and holding them there. Sometimes, it comes at the beginning of the poem, as in "Catastrophe Is Next to Godliness," which opens: "Lord, I confess I want the clarity of catastrophe but not the catastrophe./ Like everyone else, I want a storm I can dance in./ I want an excuse to change my life."

Others arrive at the end of the poem, a gut-punch like the lines that close "Good Morning America," a poem of nine, three-line stanzas: "Come in, last year's wreck, rent./ Grief's a heavy planet, and green./ I know better than to call/ each gravity's daughter to my softest cheek./ I know, and I know./ So what?" Each word clacks and bruises against the next, and the enjambment across stanzas forces both a forward rhythm and a pause. It is musical and discordant; it is a thing of beauty and a thing of pain.

Choi's collection is about endings of all sorts, those that happened in the past and those still to come, those that are always already happening. The poems mingle historical despair with alt-historical hope, and always there is family. Dedicated to the author's parents and grandparents, this collection rings with the memories of ancestors, and Choi (Soft Science) calls on them like muses. --Sara Beth West, freelance reviewer and librarian

Discover: The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On is an often heavy and always beautiful collection about endings of all sorts.

Children's & Young Adult

A Rover's Story

by Jasmine Warga

A Mars rover bravely completes his mission in Jasmine Warga's endearing, character-driven middle-grade novel A Rover's Story.

Resilience dutifully receives code and undergoes tests in a NASA laboratory to prepare for his space mission. He is "built to make good decisions" and "to avoid the problems of humans." The rover, though, takes particular interest in scientists Rania and Xander, from whom Resilience learns human emotions and behaviors including trust, fear and gratitude. Meanwhile, Rania's daughter, Sophie, writes unsent letters to Resilience in which Sophie processes her own complex feelings around her mother's attachment to her work and, as the years of the rover's mission pass, other major life events. Fellow computers warn Resilience "that Mars is no place for human emotions," but Resilience's bravery ultimately enables him to take risks that lead to the mission's success.

With very short chapters and five well-paced parts, Newbery Honor author Warga (Other Words for Home) deftly alternates perspectives between Sophie and Resilience, paralleling Resilience's child-like wonder with Sophie's emotional growth. Warga thoughtfully balances the technical aspects of this STEM story with social-emotional nuance in an uncommon and approachable blend that lends warmth and tenderness to even the more logical side characters. She credits real Mars rovers as inspiration in an author's note with additional resources for curious readers.

This Wall-E reminiscent story is an empathetic next step for fans of The Wild Robot and a natural fit for kids curious about space exploration and the unknown. --Kit Ballenger, youth librarian, Help Your Shelf

Discover: A Mars rover designed for logical space exploration learns human emotions that ultimately drive his mission's success in a hopeful, character-driven middle-grade novel with dual perspectives.

Meanwhile Back on Earth...: Finding Our Place Through Time and Space

by Oliver Jeffers

2017 BolognaRagazzi Award for Fiction winner Oliver Jeffers (A Child of Books) employs an ingenious device to depict the history of humankind through distances in space. Jeffers's distinctive art and charming wit playfully deliver a profound message of unity as a father and his two children navigate their car "at 37 mph" through the solar system.

The trio of space travelers use the time it would take them to reach various points in space--the moon (one year), the sun (283 years), Ceres (500 years), Neptune (8,000 years)--to look back at corresponding events in humanity's chronology, discovering that "humans... have always fought each other over space." The images in their car's rearview mirror show conflicts like the American Revolution, the Crusades, the Viking explorations, even the battles of the Ice Age where "early people are fighting each other with sticks and stones." Jeffers's brilliance with perspective in both prose and illustration emphasizes the insignificance of humanity's skirmishes within the whole of the solar system, "just one of billions."

Meanwhile Back on Earth is a companion piece to the art installation "Our Place in Space," but one need not experience the 10km sculpture trail to feel the impact of Jeffers's theme and gain this mind-bending perspective on people's place in the universe. His use of enormous numbers for time and distance drives home the idea that Earth's inhabitants are all much more alike than dissimilar; one simply must look from a proper distance. This endearing picture book offers a light that enables readers to see clearly. --Jen Forbus, freelancer

Discover: Oliver Jeffers shines starlight on the insignificance of human conflict and the magnitude of commonality in a clever and delightful car ride through time and space.

Man Made Monsters

by Andrea L. Rogers, illus. by Jeff Edwards

Cherokee author Andrea L. Rogers follows the harrowing history of one family's encounters with both anthropogenic and preternatural horrors in her intricate, chilling YA collection of 18 stories, Man Made Monsters. Illustrations by Cherokee artist and language technologist Jeff Edwards bring an additional layer of stark gravity to Rogers's hair-raising episodes.

The opening story, "An Old-Fashioned Girl," picks up in the middle of the Wilson family's flight to Indian Territory in 1839, "chased by human monsters, monsters who lived on blood and sorrow." Their deadly run-in with a mysterious well-dressed man sets the stage for generations of supernatural encounters. A boy in 1866 receives the intervention of fairy-like people reminiscent of the Nunnehi in "An Un-Fairy Story." A news article details a standoff between two Cherokee soldiers and a fearsome beast in "Hell Hound in No Man's Land." A young woman strikes up an unusual romance with a Goat Boy in Texas one summer in the late 1960s.

Rogers's roster of monsters draws from a diverse pool of horror genre standards, cryptids and Cherokee stories. Her disarmingly direct prose leaps nimbly between points of view, each protagonist a beautifully realized individual. Rogers integrates Cherokee words seamlessly throughout the text, along with Spanish and German where historically appropriate. Edwards's illustrations, white on black backgrounds, often incorporate the Cherokee syllabary, words running up the throat of a cat with a knowing expression and through the workings of a sinuous human heart. Teen and adult readers looking for a taste of the gorgeously gruesome should snap up this dark, engrossing jewel. --Jaclyn Fulwood, youth experience manager, Dayton Metro Library

Discover: Drawing from genre staple monsters and traditional stories, Cherokee author Andrea Rogers's short story horror collection combines supernatural and manmade atrocities.

Seen and Unseen: What Dorothea Lange, Toyo Miyatake, and Ansel Adams's Photographs Reveal about the Japanese American Incarceration

by Elizabeth Partridge, illus. by Lauren Tamaki

This reverent nonfiction work for older middle-grade readers depicts the U.S.'s harrowing history of Japanese American internment during World War II through the lenses of three professional photographers. The accompanying narration by National Book Award finalist Elizabeth Partridge (Boots on the Ground) and illustrations by Lauren Tamaki (You Are Mighty) fluidly merge the artists' visual perspectives into a multi-dimensional experience of the xenophobic response to Pearl Harbor's bombing.

Each of Partridge's three photographers--Dorothea Lange, Toyo Miyatake and Ansel Adams--approached their work recording the Manzanar incarceration camp differently. The U.S. government imprisoned Japanese-born photographer Miyatake in Manzanar; the same government later hired Lange to provide photographic evidence that it was acting humanely toward the Japanese Americans. The final member of the book's trio, Adams, entered Manzanar in 1943 at the behest of the camp's director with the goal to "convince other Americans how trustworthy and patriotic [the prisoners] were."

The photographs in each section are accompanied by Tamaki's original art, which works to incorporate and visually extend the view readers have of Manzanar. Also stretching the reader's experience is a rich collection of backmatter that includes biographies of the photographers, credits for their photographs and information about civil liberties. Each meticulously composed section of the book evokes strong feelings through the combination of imagery and history. Seen and Unseen portrays this assault on Japanese Americans with a powerful accuracy that all readers will benefit from experiencing. --Jen Forbus, freelancer

Discover: A National Book Award finalist memorably chronicles the history of the Manzanar incarceration camp by viewing the ghastly injustice through the lenses of three professional photographers.

Frizzy

by Claribel A. Ortega, illus. by Rose Bousamra

Claribel A. Ortega (Witchlings) writes buoying books inspired by her Dominican heritage. She empathically takes on the timeless challenges of "good" and "bad" hair in Frizzy, gloriously depicted by debut illustrator Rose Bousamra.

Going to the salon every Sunday is "without fail" the "worst part of the week" for Marlene. But according to Mami--and to many of their Dominican American relatives--having her curly hair straightened is the only way to be "presentable." Best friend Camilla suggests Marlene try taking her hair into her own hands with the help of online tutorials. The plan doesn't quite work--Marlene's hair becomes completely unruly--causing further exasperation from Mami and cruel bullying from other students. Mami, unsure of what she can do, sends Marlene to curly-haired Tía Ruby for the weekend. Ruby finally helps Marlene understand how "sometimes, the things we learn aren't right, but they're ingrained in us," including "hearing about good hair and bad hair every single day."

Ortega's novel is (of course) about so much more than hair. Tía Ruby gives Marlene deft lessons on multigenerational "anti-Blackness," inherited self-denial and family dysfunction--all appropriately presented by Ortega for the intended middle-grade audience. Bousamra's energetic panels are a vibrant delight, further enriched by evocative details that enhance the text. Through warm, encouraging collaboration, creators Ortega and Bousamra underscore and celebrate the joys of being "beautiful in your own way." --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: Author Claribel A. Ortega and artist Rose Bousamra's inaugural collaboration is an energetically inspiring middle-grade graphic novel about so much more than hair.

New in Paperback

The Writer's Life

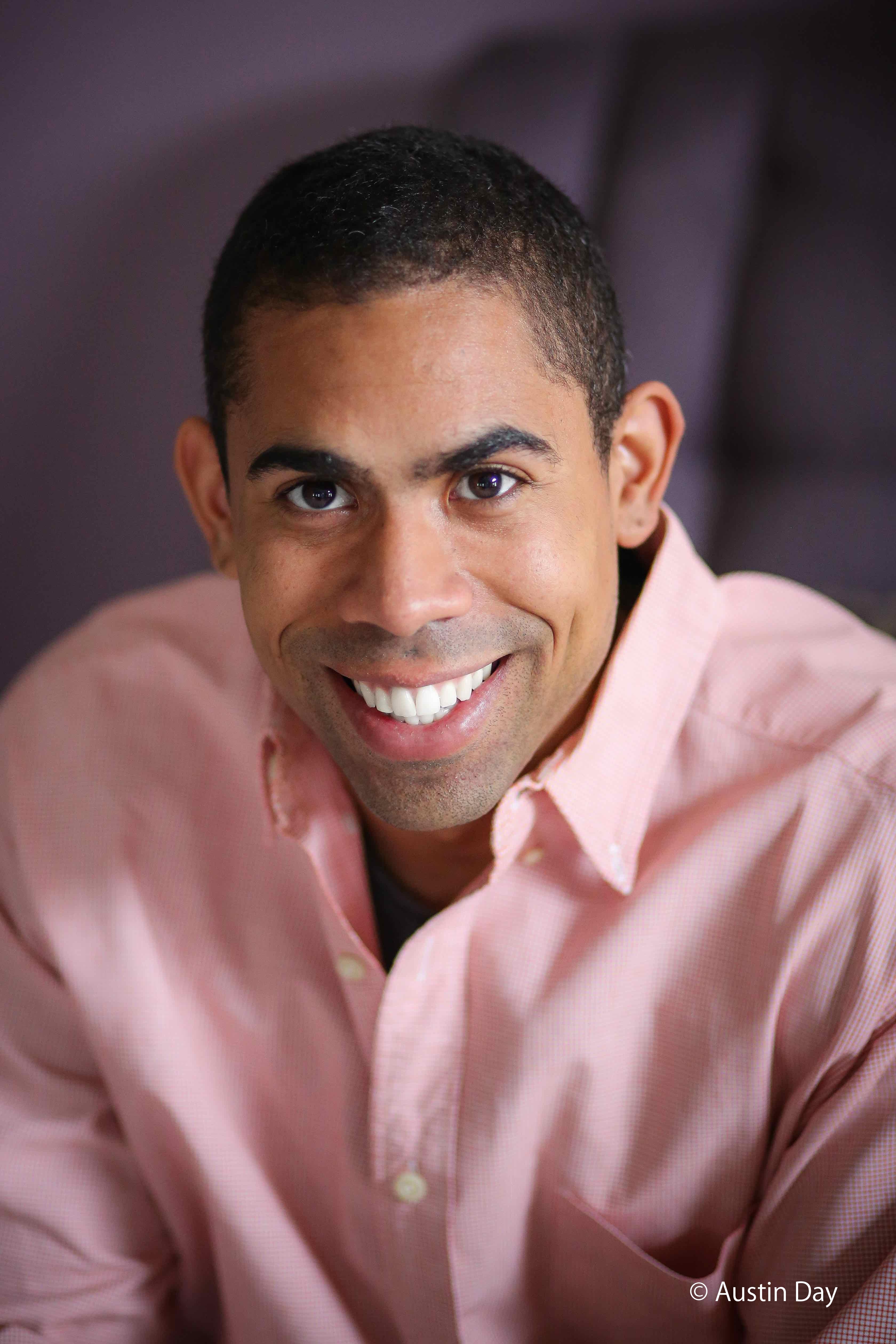

Brandon Sanderson: What Makes a Masterpiece

Bestselling fantasy and science fiction author Brandon Sanderson's many series include Mistborn, the Stormlight Archive, Infinity Blade, Legion and Skyward. His books have sold more than 21 million copies worldwide. In 2007, he was chosen to finish Robert Jordan's iconic The Wheel of Time series. He also co-hosts the Hugo Award-winning writing advice podcast Writing Excuses. Sanderson lives in Utah with his wife and children. Recently he spoke with us about the 10th-anniversary edition of his Hugo-winning novella The Emperor's Soul (Tachyon), in which a gifted magical Forger must find a way to escape her captors while finishing the most difficult Forgery of her life: re-creating the Emperor's mind and personality after an assassination attempt.

Bestselling fantasy and science fiction author Brandon Sanderson's many series include Mistborn, the Stormlight Archive, Infinity Blade, Legion and Skyward. His books have sold more than 21 million copies worldwide. In 2007, he was chosen to finish Robert Jordan's iconic The Wheel of Time series. He also co-hosts the Hugo Award-winning writing advice podcast Writing Excuses. Sanderson lives in Utah with his wife and children. Recently he spoke with us about the 10th-anniversary edition of his Hugo-winning novella The Emperor's Soul (Tachyon), in which a gifted magical Forger must find a way to escape her captors while finishing the most difficult Forgery of her life: re-creating the Emperor's mind and personality after an assassination attempt.

What does the rerelease of The Emperor's Soul mean to you?

It is one of my favorite stories that I've written. I broke in as a giant, epic fantasy writer. I don't know if I'll ever be writing consistently award-winning flash fiction, but I wanted to practice the novella. My time spent working on it culminated in this story, which won the Hugo Award, which is to date my only win for a major fiction award. It's a mark of pride to me that I was able to teach myself to write in a slightly different format.

It's also a personal story about the nature of art and what it means to be an artist. All artists have this push and pull with art. Art theory goes back for me to Plato. He asks, are all artists poor imitations of reality? I do love Plato, but that question has always stuck in my craw. I wrote a story about what art meant to me, and about what makes something a masterpiece, versus a cheap copy.

How does the real world inspire your fiction?

How does the real world inspire your fiction?

If I have a challenge in my life, it's that I do not get to write all the stories that I want to write. Some of my beautiful things that I've imagined have to be put on the shelf as something that was only for me, and I'll never get to them. But everything inspires me and, beyond that, fiction is the way I work out my relationship to the now. The way that I work out my feelings about everything, from the nature of art, to politics, to relationships. As a writer, seeing through the eyes of different people who experience the world differently than myself is how I explore what it means to be human.

The world has changed in many ways since you wrote the story, and in some ways it hasn't changed at all. How might the story look different now to readers coming to it with fresh eyes?

Criticism is its own realm, and an author is often too close to the work to know what it's going to mean to people. At its core, The Emperor's Soul is about a woman coming to understand another person while a third person comes to understand her. I feel like the world could use a bit more effort to understand, even when we don't agree. Over the last 10 years, one of the things that has become increasingly obvious to me is that we make less of an effort than we ever have to understand each other.

In the new introduction, Jacob Weisman of Tachyon Publications recounts your Hugo Award acceptance. What do you remember about that evening?

It is one of the most magical evenings of my life. I still am a little bit disbelieving. With this story, I reached back to more traditional literary inspirations, and the fact that it even got nominated was a surprise to me. Winning floored me because I was up against some very, very stiff competition. There are various times when you can say, "Man, I think I've arrived now," and that was one of those moments for me.

What should readers expect from the new edition?

We have a cool deleted scene, the first scene I wrote for Emperor's Soul. As a writer, you have to write your way into a story. Then you read it and think, Wow, this scene got me into the story, but it doesn't belong. This one has some key continuity items that are relevant to the story and series, but I let them be inferred rather than seen. I think fans of the story in particular will love reading the scene and the new introduction.

A good friend of yours advised you to cut the scene.

Yeah, Mary Robinette Kowal, a master of the short form. Her rallying cry for me was, "Brandon, fewer characters." That's how you do the shorter form. Keep it focused. It was excellent advice.

What does having a strong community of writer friends mean to you?

Writing is so solitary. You're sitting in a room for hours on end. A lot of people do that for their jobs, but they're also touching base with their team members. In writing, you're by yourself and figuring out how to fix problems, how to grow. At certain points, you hit a wall and need friends to say, "This is how I climbed that wall. This is how I went around that wall. I dug under that wall!" The stronger the writing community, the more strong writers come out of it. When writers support one another, all their writing gets better. I'm grateful to my writing communities. I like the science fiction/fantasy community in particular, how open and welcoming it is to new writers.

You're known for your productivity. What motivates you to keep creating?

I love telling stories. I love holding the finished product in my hands. I love making things. If I'm not, something's missing from my life. When I have a vacation, what I want to do is sit on the beach and work on a new story, something that no one's expecting. I want to explore how to tell a different kind of story.

WithThe Emperor's Soul, I wondered, Can I tell a story that takes place mostly in one room? Can I tell a story that delves into the nature of art without feeling heavy-handed? These are challenges I set myself. I'm chasing the experience of what it feels like to tell these stories.

If a Forger had to re-create your essence, what would be the most important facets to get correct?

A Forger would probably have a pretty easy time, because I am who I am. When you read the books, every one of those characters is a piece of me. The thing that would be most important to get right would probably be that desire to tell stories. The way I interact with art is at the core of who I am. My desire to understand others drives me. My exploration of the world would be another point to get right.

And they need to know that I love salty foods, and I do enjoy sweet foods, but never the twain shall meet. If you make a Forgery of me that eats kettle corn, you have failed. --Jaclyn Fulwood

Book Candy

Book Candy

The Oxford Word of the Year 2022 is goblin mode, "a type of behavior which is unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations."

The Oxford Australian Children's Word of the Year is privacy, with a 300% increase in usage from the previous year.

Mental Floss offered a "brief history of creepy Victorian Christmas cards."

Gastro Obscura chronicled "one man's search for the first Hebrew-lettered cookbook."

Discover Great Publishers

Introducing Hippo Park

Hippo Park's debut list reflects the joyful, surprising, often befuddling and endlessly fascinating world children live in. Editorial director Jill Davis says, "We want to make the kind of books kids ask for again and again--with stories that tickle their funny bones, respect their intelligence and support their need for emotional connection. Our focus is on what children see and feel when they open up our books and look inside--words and ideas that are funny, silly and often true, and illustrations that convey emotion when words might not. We like to say that we take silly seriously, and we hope our books will bring children wonder and delight."

Jill talks about each of the books she'll be gifting this holiday season.

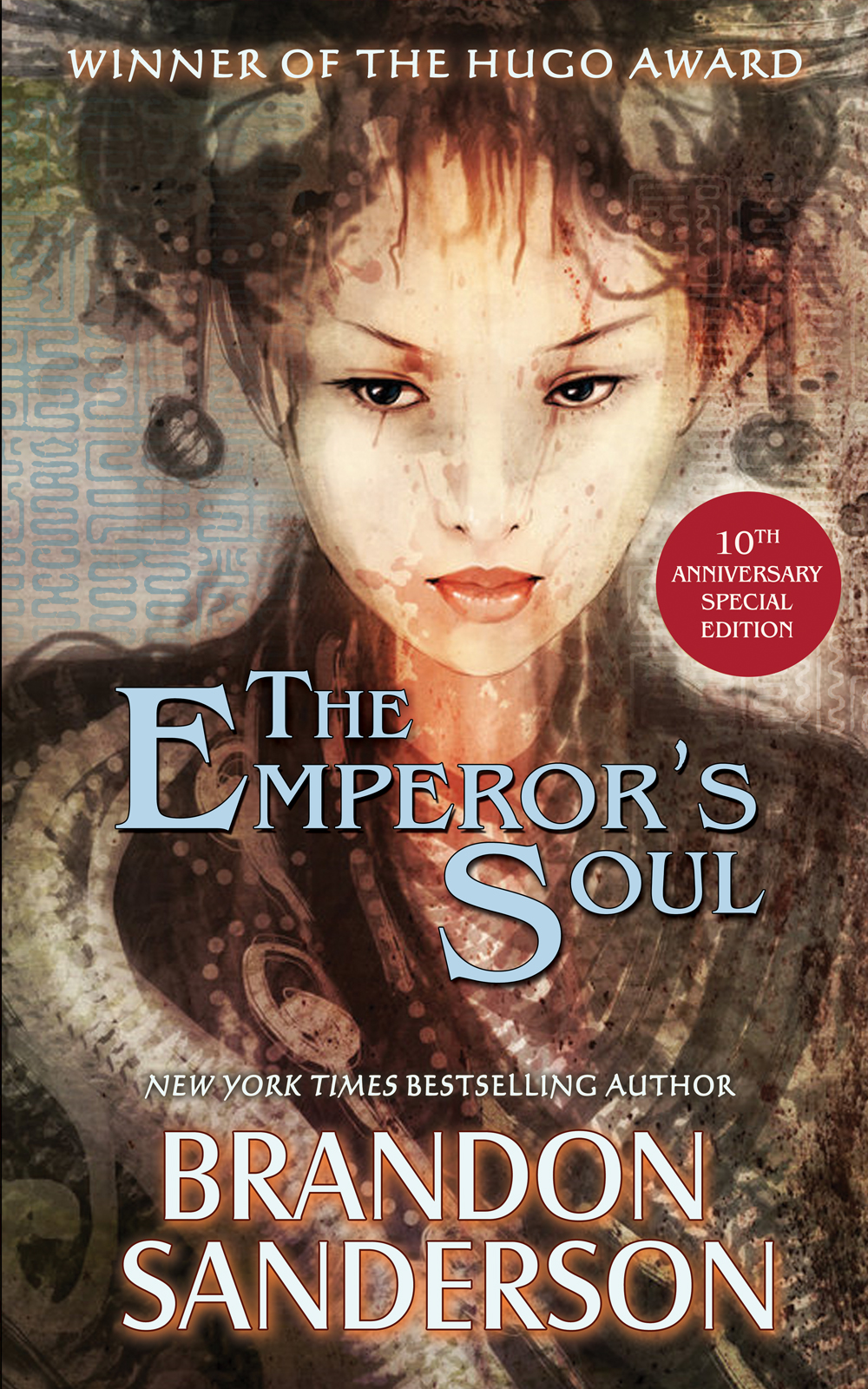

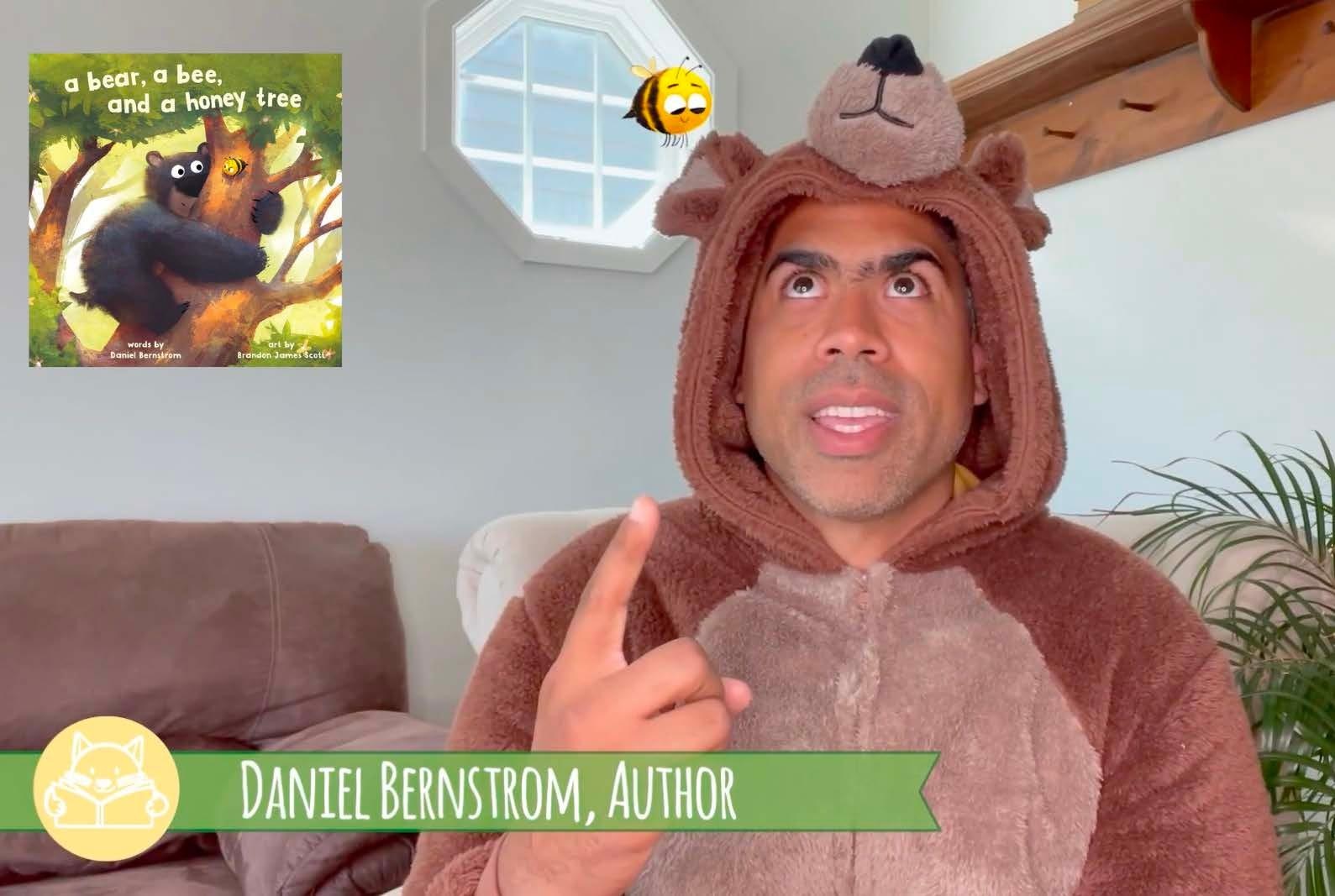

A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree by Daniel Bernstrom, illus. by Brandon James Scott (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 40p., ages 3-7)

A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree by Daniel Bernstrom, illus. by Brandon James Scott (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 40p., ages 3-7)

Brandon James Scott's young, funny and lush artwork paired with Daniel Bernstrom's spare, rhyming text is going to steal hearts! The text and illustration work as one, making A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree feel like an animated short. It's definitely a crowd-pleaser for story time: a classic read aloud in a nice big trim size with delicious characters that really pop and anchor the appealing art.

Tiny Spoon vs. Little Fork by Constance Lombardo, illus. by Dan Abdo and Jason Patterson (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 48p., ages 4-8)

Tiny Spoon vs. Little Fork by Constance Lombardo, illus. by Dan Abdo and Jason Patterson (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 48p., ages 4-8)

I'm delighted to share the bubble gum colors and comic ebullience of Tiny Spoon vs. Little Fork. This is a book about how rivalry can lead organically to teamwork--hoorah! It's also my fifth book with the marvelous Constance Lombardo, which is very much worth celebrating.

How to Draw a Happy Cat by Ethan T. Berlin, illus. by Jimbo Matison (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 40p., ages 4-8)

How to Draw a Happy Cat by Ethan T. Berlin, illus. by Jimbo Matison (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 40p., ages 4-8)

The book takes the form of a drawing lesson that goes off the rails when Cat--who's been drawn with a happy face--WON'T STAY HAPPY! And now you, the reader, have to fix it! A gentle and mischievous narrator pulls you along, and also pulls your chain! For all the action-packed laughs and screw-ball fun in this book, there's also a social emotional message that even the grown-ups will appreciate: How burdensome it can be to take on the task of making others happy!

Come On In: There's a Party in this Book! by Jamie Michalak, illus. by Sabine Timm (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 40p., ages 4-8)

Come On In: There's a Party in this Book! by Jamie Michalak, illus. by Sabine Timm (Hippo Park, $18.99, hardcover, 40p., ages 4-8)

Just look at this cover with its peek-through window for dear, sweet Lemon. Come On In is the dessert of this launch list. The conceit: Lemon really wants to go to the big party, but each time she opens a door, there's a small group of... cats in boots! Or fruits in suits! But they're celebrating all by themselves! So, where's the party where everyone is together, mixing it all up and having a blast? After arriving at home, sad and alone, she has an idea of her own--to shake up the book and shout COME ON IN! And all the creatures from behind the doors "come on in" for one big unforgettable fiesta! Sabine Timm's photographs of fruits, cakes, bread creatures and all types of miniatures have earned her almost 170,000 Instagram followers and I knew I had to find a collaborator for her. I was so happy when Jamie Michalak created a story for Lemon that brings her and her friends to life.

Herbert on the Slide by Rilla Alexander (Hippo Park, $9.99, hardcover, 24p., ages 2-5)

Herbert on the Slide by Rilla Alexander (Hippo Park, $9.99, hardcover, 24p., ages 2-5)

This is the start of an adorable series called the Hippo Park Pals. We were so smitten with Herbert, the handsome hippo created by Rilla Alexander for our logo, that we suggested a series to Rilla. We considered the ecosystem of the playground and our audience emerged as 2-to-5-year-olds who, now walking and talking, are desperate for independence. We knew these weren't board books for chewing on, they had to be precious, special and make little kids feel big. Each book has a dust jacket with flaps, and 32 pages of a satisfying story. It's the perfect stocking stuffer!

A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree

Daniel Bernstrom & Brandon James Scott

|

|||

|

|||

Daniel Bernstrom is an accidental picture book writer. He repeated first grade because he could not read. Today, Bernstrom writes picture books that have been nominated for several state reading awards, and he teaches as a full-time English instructor at Minnesota West Community and Technical College.

By day, Brandon James Scott is a Creative Director working in animation; by night, he illustrates picture books. For more than a decade, Brandon has worked on a range of animated entertainment including his own creation, the award-winning series, Justin Time. A born and raised Canadian, he lives with his family in Toronto.Here the two creators discuss their sly and snappy picture book A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree.

Daniel Bernstrom: Brandon, you were on vacation. Welcome back!

Brandon James Scott: Thanks! I got back from taking my family to a cottage--which, as a Canadian, is a must-do thing each summer. Going in the lake, campfires... it's the best.

Bernstrom: I did that a few times. I remember roughing it out in the Alaskan wilderness for a week. Caught salmon from the stream, fought off mosquitoes, avoided bears, canoed down the river. Scarred me forever.

Scott: What are you talking about, that sounds amazing. Wait. Did you say bears?

Bernstrom: Yep, saw a couple. Why--do you like bears?

Scott: I think of all the animals that you might run into out there in the world, the bear is just so strong and demands respect. I also like how they look when they're grumpy.

Bernstrom: I love your grumpy bear drawings. What got you started in illustrating?

Scott: When I was young, I loved to draw. And I realized early that the more I did it, the better I got. I became the "art guy" in elementary class and I stuck with it.

Bernstrom: I love how funny your art is. There are little jokes everywhere. Are you funny in real life?

Bernstrom: I love how funny your art is. There are little jokes everywhere. Are you funny in real life?

Scott: I'll say I find it very hard to take most things seriously.

Bernstrom: I keep hearing that our book's ending is "controversial." Explain why?

Scott: Well, the ending feels just right to me. However, it isn't spelled out--you have to look closely at the last page to get the full story. (Dun-dun-dunnnn.)

Bernstrom: For my part, I wanted the promise of resolution: the bear going back for the honey. But I knew for the ending to work, the illustrator needed to see things his way. You did just that. I remember when our editor Jill Davis said, "There needs to be a bear on the last page." I said, "Jill, look closer." The surprise was exhilarating.

Scott: And that reminds me how supportive and collaborative you were. It's a joy as an illustrator to be able to bring your own extras through images. I wanted to thank you--and Jill and art director Amelia Mack--for that!

Bernstrom: I think artists see so much. That's why I felt it important to not get in the way. Speaking of Amelia, what's it like working with her?

Scott: Amelia was awesome--she was involved in a wonderful way to make the story stronger. Sometimes when you're at the picture stage you can get caught up with "does this look good" or "can this look different" but taking a step back even further and asking "does this support the story" is the most important thing, always.

Bernstrom: I remember you two focusing on the eyes of the bear and bee to tell so much of the story. Or was that your idea?

Scott: We talked about that a lot. Eyes are such a big part of characters. One thing I love to do is to make a character's eyes say something different than what the text might imply, just to add another little dimension. Bears, bees... we're all complicated. What was it like working with Jill?

Scott: We talked about that a lot. Eyes are such a big part of characters. One thing I love to do is to make a character's eyes say something different than what the text might imply, just to add another little dimension. Bears, bees... we're all complicated. What was it like working with Jill?

Bernstrom: Working with Jill is like taking a masterclass in picture book writing. She'll never let me get by with a "sloppy" or "redundant" word. She wants every word to glow, and every word needs a VERY good reason to be there. She works with the author to make that happen. She also loves making books funnier.

Scott: She's so great. Do you think we'll see any other adventures for this bear?

Bernstrom: I hope so! I have five or six bear ideas. He's such a fun character, especially after you made him come alive. You game for illustrating more?

Scott: Have you seen my art? Half of my work has bears in it.

Bernstrom: If we do another, I'll have to visit you in Canada, and you can show me what's so fun about the outdoors.

Scott: Deal. We'll call it field research.

Great Reads

Rediscover: Five Tuesdays in Winter

Last year, novelist Lily King's first short story collection, Five Tuesdays in Winter, was published by Grove Press. A Shelf Awareness review of these "10 stories of love and longing, coming-of-age and declining, friendship and families" called the book "a richly rewarding experience" with "crisply descriptive prose" and an "optimistic perspective." These tales track a wide variety of characters--a neglected teenager nurtured by college students, a grandfather with a comatose granddaughter, a bookseller smitten with his part-time employee, a pregnant writer contending with all the men who have ever silenced her voice--all steered toward love, even amid tragic circumstances. Five Tuesdays in Winter was named a Best Book of the Year by NPR and Kirkus and was a finalist for the Story Prize.

Last year, novelist Lily King's first short story collection, Five Tuesdays in Winter, was published by Grove Press. A Shelf Awareness review of these "10 stories of love and longing, coming-of-age and declining, friendship and families" called the book "a richly rewarding experience" with "crisply descriptive prose" and an "optimistic perspective." These tales track a wide variety of characters--a neglected teenager nurtured by college students, a grandfather with a comatose granddaughter, a bookseller smitten with his part-time employee, a pregnant writer contending with all the men who have ever silenced her voice--all steered toward love, even amid tragic circumstances. Five Tuesdays in Winter was named a Best Book of the Year by NPR and Kirkus and was a finalist for the Story Prize.

The paperback version of Five Tuesdays in Winter was released on November 1, 2022. On November 8, Grove Press published new editions of two of Lily King's previous novels: The English Teacher (2005) and Father of the Rain (2010), both with new covers. The English Teacher, about a mother's impulsive marriage to a widower, won the Chicago Tribune Best Book of the Year. Father of the Rain, which explores a volatile father-daughter relationship over several decades, won the 2010 New England Book Award for Fiction. King is also the author of Writers & Lovers (2020) and Euphoria (2014), which won the Kirkus Prize for Fiction and the New England Book Award for Fiction. --Tobias Mutter

Read what writers are saying about their upcoming titles