It started as Symptoms,

more than seven years ago,

with a memory from David Small's childhood:

The trip that he and his mother and brother used to take

at the end of the day as a one-car '49 Ford family

going to pick up his radiologist father from the hospital.

It ended with the image of David as "a naughty boy"

who rode the hospital elevator and saw

"that little man in the jar."

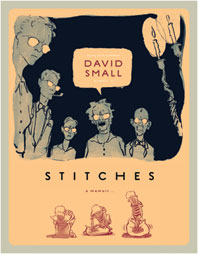

David Small began as an editorial artist

and a children's book illustrator.

He has won a Caldecott Medal.

He had always resisted the graphic novel form

with its "little pictures," as he put it.

But in Paris four years ago with his wife, Sarah,

Small saw the possibilities in comics.

"The French were doing books about serious, mature subject matter,

a lot of them influenced by bande dessinées," said Small

(literally translated as 'drawn strips').

"I came home from Paris that winter and,

after my day in the studio doing children's [illustrations],

I'd sit at the kitchen table, fix myself a martini and draw.

I started with the man in the jar."

"I was six," the book opens,

written like white chalk on a blackboard.

Next, the word "Detroit" appears

opposite the image of the Ford Rouge Plant.

"It was like Dante's Inferno," Small said of the auto factory.

A series of wordless images takes readers

from the factory to a cookie-cutter block.

Inside the living room of a seven-room colonial,

a boy is on his belly, drawing a rabbit.

"I've done that my whole life," Small said,

"Like a bell jar coming down around David

and having nothing but my drawing implements."

Hardly a word is spoken in this house:

"Mama had her little cough."

Dad has his punching bag ("pocketa pocketa pocketa"),

and brother Ted has his drums ("bum bum bum").

As for six-year-old David, "getting sick, that was my language."

For his sinus problems,

his radiologist father gave David many X-rays.

We see the six-year-old's eyes--

just the eyes--

staring into the lens of an X-ray machine.

One day at the hospital,

six-year-old David disobeys his mother.

He rides the elevator to the fourth floor ("Pathology").

Those same little-boy eyes stare into a jar with a "little man" in it.

The child imagines a wordless sequence:

The little man opens his eyes and stares back at the boy,

then bursts from the jar and gives chase.

Young David narrowly escapes via the elevator.

This is the scene that Small wrote down

and showed to his agent, Holly McGhee.

"This is going to be your novel," she said.

"It has a great voice."

"I said 'O.K.' and stopped," said Small.

"I didn't know where to go with it.

I didn't think I'd ever get through anything

that needed that much mental organization."

But several years ago, when David Small had a dream--

the dream that ends the book--

that made him think,

"It's still in me and I have to do something about this."

To Small's editor, Bob Weil, the story was like Metamorphosis,

"for like Kafka's boy-turned-insect, Gregor Samsa,

David Small awakes one day from a supposedly harmless operation

to discover that he has been transformed into a virtual mute."

Those "200 to 400 rads"

the father gave his son to treat his sinus infections

led to throat cancer.

David comes to, at age 14, with one vocal cord,

speechless in a silent home.

After David takes off in one of the family cars

and lands in the Wayne County Jail,

"Even Mrs. Small, as skinflinty as she was,

realized that she had a big problem," as Weil put it.

She sent him to a psychiatrist.

When she drops him off at his first appointment, she says:

"It's like throwing money down a hole, if you ask me."

Down the rabbit hole.

The psychiatrist guides David into Wonderland.

"The child who is not loved and never touched,

never picked up, reaches up to the world with his eyes,"

the psychiatrist told Small.

"That's why you're an artist, David."

And so Small was compelled to turn

to the graphic novel form,

using a sequence of images to tell the story of

how the bell jar came down around him

and how art saved his life.

"I see graphic novels

as complete compositions of music

with a beginning, a middle and an end," said Weil.

He encouraged Small to take his seminal images and use them.

"How can it replay at the end?" Weil said.

"Listen to the beginning."

The eyes,

the eyes of a six-year-old,

staring into the X-ray machine,

staring into the eyes of the little man in the jar,

staring into the eyes of Jesus

on a crucifix in his punitive grandmother's house.

The eyes of 15-year-old David when his doctor father

admits he gave his son cancer,

and the teen's face transforms into that of a six-year-old boy again.

The eyes of David's mother

when he finds her in bed with Mrs. Dillon,

glamorous Mrs. Dillon, the first to notice the lump on David's neck.

And the eyes of 14-year-old David

as he confronts his mother in the hospital,

and the image of half of David's face

and half of his mother's face forming a whole portrait.

"We take in our parents and we become them

because they're our only teachers when we're young,"

says Small. "I have my mother in me.

When I meld our faces together,

I say, 'Look, I'm treating her exactly as she'd treated me.'"

The stairs

down to his father's punching bag,

down to his grandmother's coal-burning furnace,

Grandmother dragging David up the stairs to be punished.

And the stitches and the stairs.

When 14-year-old David takes off his bandage--

"A crusted black track of stitches;

my smooth young throat slashed and laced back up

like a bloody boot"--

the pictures zoom in closer and closer

until the stitches become fine white horizontal lines

across one dark Stonehenge-like protrusion,

perfectly mirroring the carpet rails of the stairs,

the stairs that lead David up to his mother's desk

where he finds a letter to his grandmother:

"Of course the boy does not know it was cancer."

Panels like movie stills record his response:

" 'Of course the boy . . .

'Does not know . . .

The boy. The boy. The. Boy. Does. Not. Know."

The eyes. The eyes. We see only the eyes.

"He freezes consciousness on the page," said Weil.

Alice in Wonderland

At six, the boy lies on his belly and draws a rabbit.

He escapes his scary thoughts by disguising himself

as Alice in Wonderland

with a yellow towel over his head.

"I thought it must be her hair," Small recalls,

"That gave Alice the magic ability to travel to a land

of talking animals, singing flowers and dancing teapots."

In a later draft, Small cut that scene of Alice.

"You took out the yellow towel" McGhee said, "That was my favorite part!"

"I realized I hadn't gone deep enough," said Small.

"When I remembered further the bullies in the neighborhood,

being chased and called a homo and a queer

[when I was wearing the yellow towel],

that's when it came together and seemed meaningful."

The White Rabbit:

"I wasn't looking forward to illustrating

the process of psychoanalysis," said Small.

"There can't be anything more boring

than two people sitting in an office talking.

Then one day I was telling a friend about this problem,

and he said, 'Why don't you have him be like a fairy on your shoulder?'

'Like Tinkerbell?' I said and laughed,

and then ran home and turned him into the White Rabbit."

"The White Rabbit," Small continued,

"is like the usher into another world."

The White Rabbit tells David:

"Your mother doesn't love you."

We see those eyes, the 15-year-old eyes, and one tear.

Then a torrent of rain pummels all of Detroit,

the Ford Rouge plant,

the cookie-cutter neighborhoods,

the darkened seven-room colonial houses,

the abandoned lawn-mowers.

Until at last the world is cleansed.

In the words of Bob Weil:

"This is a silent movie

masquerading as a graphic novel."

The final dream:

The boy at six with a remote-control car

in a French-style house

surrounded by a formal garden.

"I started looking at the symbolism in a Jungian way," Small said.

"The formal enclosed garden

always means something about your career,

the way you've organized your life, your outside world.

The water in the center of it is the unconscious.

Instead of going outside myself, because I was afraid,

I sent the car around, and it worked very well

until it falls into the water.

That's when I have to come out of the house.

The car is my career.

It was going around all those paths so well until--

Wham! It hit my subconscious mind--

until I went out.

It's at that point in the dream,

I see that direct path from me to the madhouse

and my mother beckoning me to go there.

I woke up in a sweat and said . . .

I've got to go out and put my hand in that pool."

Weil told Small: "Be like the cormorant

who dives beneath the water

and comes up with the fish."

"It was hard to do," Small said.

"But I did it."

--Jennifer M. Brown

Stitches by David Small (Norton, $23.95, 9780393068573/0393068579, 344 pp., September 8, 2009)