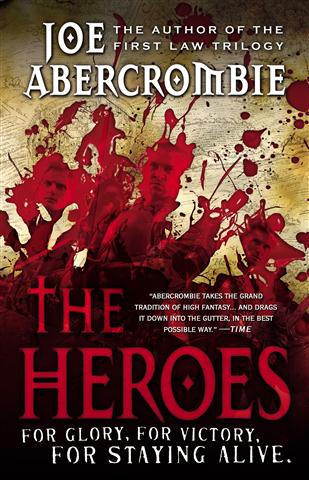

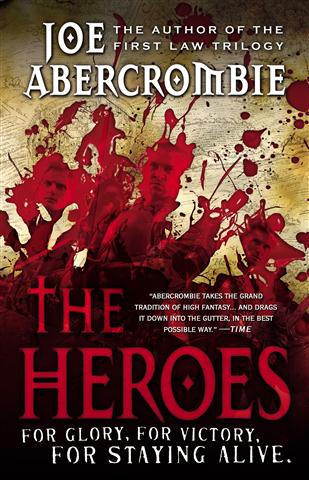

If maverick film director Sam Fuller had ever made a fantasy sword epic, it would have looked a lot like The Heroes: an unflinching portrait of, as Joe Abercrombie (the First Law trilogy) remarks in the midst of one battle scene in his latest novel, "the blood, the corpses, [and] the spreading panic" of three days of fighting over a marginally strategic hill in a largely meaningless war.

If maverick film director Sam Fuller had ever made a fantasy sword epic, it would have looked a lot like The Heroes: an unflinching portrait of, as Joe Abercrombie (the First Law trilogy) remarks in the midst of one battle scene in his latest novel, "the blood, the corpses, [and] the spreading panic" of three days of fighting over a marginally strategic hill in a largely meaningless war.

The armies of the Union have pushed their way forward to the valley of Osrung, a small town that is bordered by The Heroes, a hill with a circle of rocks around its summit. (Some say the henge is the burial site of legendary warriors of the past, but the more cynical characters don't care one way or the other.) They are met by the forces of Black Dow, a northern chieftain whose right to rule has been established by killing his rivals. Abercrombie takes this basic setup and populates it with a wide range of characters, from the grizzled but honorable mercenary Craw and Gorst, a disgraced Union officer hoping to win his way back into the king's good graces, to Beck, a young northern volunteer who quickly learns how little glory there is to be found in war, and Finree, the ambitious wife of another middling officer. During the combat sequences, the narration flits almost imperceptibly from one perspective to another, repeatedly crossing the front lines and blurring readers' perception of the big picture--because, until the fights settle down, "the big picture" is basically irrelevant.

"You think how stupid people are most of the time," explains Tunny, a Union corporal who's made a career of staying away from the front lines whenever possible. "The foolishness and the vanity, the selfishness and the waste. The pettiness, the silliness. You think in a war it must be different. Must be better... be heroic." Not so: "People are even stupider in a war than the rest of the time. Thinking about how they'll dodge the blame, or grab the glory, or save their skins, rather than about what will actually work. There's no job that forgives stupidity more than soldiering. No job that encourages it more."

Tunny's logic largely holds, up the chain of command on both sides of the war: the vainglorious Union army is pressed into an unwinnable battle due to political pressure, while Black Dow's loose alliance is targeted for dissolution by the scheming Calder, a disgraced noble who hopes to convince his peers of the futility of the whole conflict. What little heroism there is to be found in the battlefields is primarily an accident of circumstance or immediately undercut by tragedy.

Abercrombie freely embraces the anachronistic elements of his take on a fantasy setting so archaic that cannons are depicted as a form of magic--the novel's sardonic epigrams come from the likes of Brecht, Will Rogers and Mickey Mantle, while individual chapters have titles like "Hearts and Minds" and "Stuff Happens." Still, it would be a mistake to read any overt parallels to Vietnam or Iraq (or the early years of the U.S. Civil War) into his imaginary battle. Instead, he's taken bits and pieces from all sorts of war stories and assembled them into a devastatingly realistic look at the emotional and moral landscape of military combat--never mind that it's set outside our historical reality.--Ron Hogan

Shelf Talker: You could easily hand The Heroes to readers of fantasy icons like George R.R. Martin and Brandon Sanderson; it'd be interesting to see what fans of military historical fiction like Steven Pressfield's Gates of Fire or David Anthony Durham's Pride of Carthage would make of Abercrombie.