Yes.

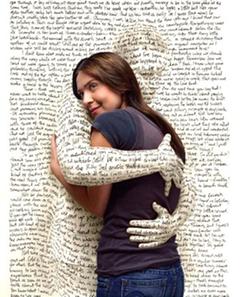

You might think the inspiration for this week's column comes from my being stuck in single-digit Northeastern temperatures while all the cool kids are partying at ABA's Winter Institute in New Orleans. Am I just retreating behind a flimsy veil of literary references for solace?

Yes.  I mean... No. My interest in the books-as-friends conundrum was actually prompted by a couple of factors, one being Rick Gekoski's piece in the Guardian earlier this week under the provocative headline "Some of My Worst Friends Are Books."

I mean... No. My interest in the books-as-friends conundrum was actually prompted by a couple of factors, one being Rick Gekoski's piece in the Guardian earlier this week under the provocative headline "Some of My Worst Friends Are Books."

While acknowledging that authors have traditionally been granted the right to be "inhabited by persons and voices," Gekoski considered the comparable experience among readers, who are also "invaded by voices.... It is a heady relationship, and can make our everyday ones seem pale and listless. It is no wonder that people claim that reading provides us with the best of friends. Dickens refers to 'the friendships we form with books,' while Charles Lamb regarded books as 'the best company.' "

Gekoski noted that "an admired writer is a peculiar but superior form of 'friend.' There are a number of senses of the term in which this seems true: someone you can turn to; someone who has wisdom to transmit; who has been a constant and trusted presence; who can share similar experiences with us; who can give without asking anything in return."

That lack of "return" proved a bit problematic for Gekoski, who conceded that a book "is not company. We engage with it, argue with it, carry it around in our pockets and minds, are haunted by memories of it for years. But it doesn't argue back, doesn't engage, never inquires how our day has been, gives only what it wishes. Books are selfish. Everything, every word, is on their terms. That's what I like about them."

But book friendships have their own particular layers of complexity, as well as more give and take than he suggests. My best book friends do argue back (often when I need their scolding the least); they do engage; and I really don't want them to inquire how my day has been. If a book "gives only what it wishes," then why do we find hidden--even unintended--meanings within the pages?

Another contributor to my interest in book friendship is The Man Within My Head, Pico Iyer's recently published memoir exploring his long "friendship" (I don't know what else to call it, except perhaps psychological kinship) with Graham Greene's work and life.

For Iyer, the "return" is both tangible and spectral: "Walking through a book by an author long dead is not a comforting experience; I began to feel I was a compound ghost that someone else had dreamed up, and his novels were my unwritten autobiography."

He accepts the oddness of this one-way friendship between writer and reader, noting the irony that "the man who bares a part of his soul on the page soon finds that his friends are treating him as strangers, bewildered by this other self they've met in his book. Meanwhile, many a stranger is considering him a friend, convinced he knows this man he's read, even if he's never met him. The paradox of reading is that you draw closer, to some other creature's voice within you than to the people who surround you (with their surfaces) every day."

The bookcase near my desk shelters a few of my best book friends, some of whom I've known for more than four decades. They ask little of me, but give much in return. "I do then with my friends as I do with my books," a small leather-bound edition of Emerson's Essays counsels sharply, as is its way. "I would have them where I can find them, but I seldom use them.... I will receive from them not what they have but what they are. They shall give me that which properly they cannot give, but which emanates from them."

Can a book be your friend? Absolutely, though I'll concede that a book will never buy you a beer in New Orleans during WI7 and talk for hours about... books.--Robert Gray (column archives available at Fresh Eyes Now)