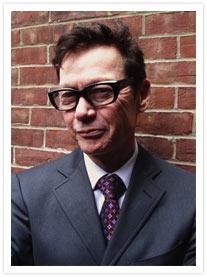

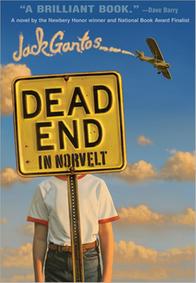

On Monday in Dallas, the 2012 Newbery Committee awarded Jack Gantos's Dead End in Norvelt its top prize. The author once again draws from his own life (even naming his novel's hero "Jack Gantos") to show how a model community created in the 1930s shaped the lives of its townspeople--particularly Miss Volker, the town nurse, historian and obituary writer, and young Jack, who acts as her hands when arthritis handicaps hers.

On Monday in Dallas, the 2012 Newbery Committee awarded Jack Gantos's Dead End in Norvelt its top prize. The author once again draws from his own life (even naming his novel's hero "Jack Gantos") to show how a model community created in the 1930s shaped the lives of its townspeople--particularly Miss Volker, the town nurse, historian and obituary writer, and young Jack, who acts as her hands when arthritis handicaps hers.

Congratulations!

Thank you.

When you won the Scott O'Dell Award for Historical Fiction last week, we had to pause before realizing--ah yes, the setting is the summer of 1962, and it is historical fiction!

That's, let's see, exactly 50 years ago. I think you can get antique license plates for a 1962 car. Somebody said, "How does it feel to be given an award for a historical novel where you're the main character?" When you put it that way, I'm feeling a little crusty.

A member of the Newbery committee told us that when you got the call that you'd won, you responded, "History makes history!" Is that true?

A member of the Newbery committee told us that when you got the call that you'd won, you responded, "History makes history!" Is that true?

Yeah, I think I said, "It's really great that I wrote a book about history that's made history." That popped out of my mouth at that moment. I think it was the one good line I had.

We hadn't known about homestead communities, and Eleanor Roosevelt's role in her namesake town, Norvelt, until your novel came along.

These homestead communities were started in the early to mid-'30s, right after FDR got in, and Eleanor was a big part of it. There were about 100 of them. They might go all the way to the Pacific, but I've seen them as far west as Phoenix. The government brought in their own architects and parceled out the lots. In Western Pennsylvania they were like little Cape Codders. In Phoenix, they were all adobe houses.

Miss Volker, who suffers from arthritis and for whom young Jack writes the obituaries, is such a memorable character. Is she based on a real person?

I changed her name, but she's a real person. If you use the real name and attach unreal aspects to them, it seems a little unfair. Even if they're dead. Which she is. She was old then. Me, I don't care what I do with me. I'm making myself up as I go along. It's hard for me to even be me. My dad has passed. I don't think my mom has read the book, but if she did, she'd probably roll her eyes and say, "Aw, Jackie," and be happy with the award.

Is Miss Volker's house still in Norvelt?

Her house is still there. The nice gentleman who lives there keeps it up perfectly. I don't know if she'd like the color--it's robin's egg blue. When she had it, it was a buttery yellow. But it's in ship shape, probably the best shape of any house in Norvelt. He's one of those bachelor guys who takes pride in his house and has a perfect garden. He lives right next door to my mom's brother, my Uncle Bill.

What ignited your interest in setting a novel in Norvelt?

After my aunt died, my mother asked me to give the eulogy in the original Norvelt church. Aunt Nancy had had disabilities and later developed Alzheimer's. But she was lovely. I said to the congregation, "Only in this town of community values could my aunt grow up and not feel she was a disabled person." Then I started giving the history of Norvelt. People came up to me afterwards and said, "I didn't know that about Norvelt." It seemed to me that the great history of the town had lifted like a fog, and people no longer saw it. They didn't realize what the universal values of that town were, that it was a helping-hand town, and the government had that value as well. I started thinking more about Norvelt, and how valuable history was.

Your book makes a case for pacifism, when Jack's father tells him about his experience as a war veteran, and also when Jack reacts to the death of a deer by writing an eloquent obituary for the animal.

All of that is very intentional in the book. That gunplay [near the opening], when Jack's shooting guns at movies, at fictional characters on a screen, it's just a game. When you really read history, you realize that real people die for the flimsiest and most whimsical of reasons. Some for great and honorable reasons, some for flimsy reasons. You always feel like you have more in common than not--that idea that [Jack's father states]: when you come face to face, you'd rather shake their hands than shoot them. I hope kids who read the book will feel the same way.

Who'd have believed that you'd go from running drugs through Florida--the subject of your memoir A Hole in My Life--to occupying a carrel at the Boston Athenaeum?

Who'd have believed that you'd go from running drugs through Florida--the subject of your memoir A Hole in My Life--to occupying a carrel at the Boston Athenaeum?

Oh yeah. And why not? I was just thinking of that. In [Tuesday's] edition of USA Today, the opening line read, "Jack Gantos, who spent 18 months in prison for drug smuggling, just won the Newbery Award." Some interview I had yesterday, or maybe it was a friend--they've all run together--asked, "Hey, are you the first ex-con who has ever published a Newbery?" We'll have to run a search on that.

An oft-mentioned observation in Dallas was that we'll get a great speech in Anaheim in June....

Somehow along the way I've developed a reputation as a talker. [Laughter.] I have received so many e-mails from librarians saying, thank you, kids actually like your books. It's been nice to know over the years that people like my books. You wonder sometimes whether humor will get the recognition it deserves. --Jennifer M. Brown