Attila Ambrus was released Tuesday after 12 years in a Hungarian prison. He is now 44 years old. That may not seem like breaking news in the publishing industry, but it is to this former bookseller. Attila is more than just a character in a book I read seven years ago. For the past week, I've been communicating with Julian Rubinstein, author of Ballad of the Whiskey Robber: A True Story of Bank Heists, Ice Hockey, Transylvanian Pelt Smuggling, Moonlighting Detectives and Broken Hearts (Little, Brown, 2005). He traveled to Hungary for the release of his friend and the subject of his book.

For the past week, I've been communicating with Julian Rubinstein, author of Ballad of the Whiskey Robber: A True Story of Bank Heists, Ice Hockey, Transylvanian Pelt Smuggling, Moonlighting Detectives and Broken Hearts (Little, Brown, 2005). He traveled to Hungary for the release of his friend and the subject of his book.

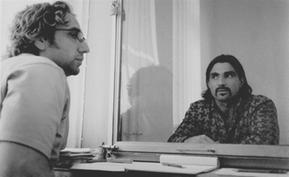

Yesterday, Rubinstein observed that Attila "has been part of my life for 13 years now, so this is all still sinking in for me, has been quite intense, still only two days since his release.... I met Attila in a private apartment of a friend last night. Only the few people closest to him were there. He hadn’t spoken to any media yet (though erroneous reports about him are all over the news.) There’s no easy way to describe what it’s like to be so close to someone who's a piece of living history and who's also so vulnerable. He was always an anachronism. He has the 'betyar' (bandit) honesty and a purity that was still there last night. Those of us who care about him are just hoping right now that he finds a way to make a life for himself."

There's the man, and then there is Rubinstein's book, which is how I met Attila. We all have that personal list of books we feel like we "discovered"; books we recommend to people who later come back and say, "I never would have found that anywhere else." Then it becomes their discovery.

When I was a bookseller, Ballad of the Whiskey Robber was one of those titles I could sell to almost anyone--men, women, readers, nonreaders, even people who claimed they didn't like nonfiction. Sometimes I found myself saying it "reads like a novel" (a meaningless, if effective, handselling point if ever there was one), though had this book been a novel, the author would probably have been advised to tone down its larger-than-life details.  A Transylvania-born Hungarian, Attila defected from Romania to Hungary in 1988. He struggled initially to find his way in Budapest, but evolved over time from a poverty-stricken refugee who owned only the clothes on his back to a janitor/Zamboni driver for a hockey team, a building superintendent, a pelt smuggler, a willing--if inept--professional goalie (he once gave up 88 goals in six games) and, ultimately, one of Budapest's most successful bank robbers and a modern-day legend.

A Transylvania-born Hungarian, Attila defected from Romania to Hungary in 1988. He struggled initially to find his way in Budapest, but evolved over time from a poverty-stricken refugee who owned only the clothes on his back to a janitor/Zamboni driver for a hockey team, a building superintendent, a pelt smuggler, a willing--if inept--professional goalie (he once gave up 88 goals in six games) and, ultimately, one of Budapest's most successful bank robbers and a modern-day legend.

Because of his penchant for drinking whiskey before making his "unorthodox requests for withdrawal," he was dubbed the Viszkis Rabló (Whiskey Robber) by the host of the TV show Kriminális, who also noted that Attila robbed institutions by "asking for the money--because that's how he does it: he asks."

Given the turbulent state of the country's political structure and economy at the time, Attila's reputation was burnished by generally good publicity. An editorial in the Hungarian daily Magyar Hírlap, for example, suggested Attila was attacking an unjust system: "He didn't rob a bank. He just performed a peculiar redistribution of the wealth, which differed from the elites only in its method." In an e-mail last week, Rubinstein noted that "Attila's crime spree so obviously struck a chord with people disillusioned about the corruption in the political and banking system in nascent capitalist Hungary. Attila's robberies of state-owned banks as his choice target drove this point home."

In an e-mail last week, Rubinstein noted that "Attila's crime spree so obviously struck a chord with people disillusioned about the corruption in the political and banking system in nascent capitalist Hungary. Attila's robberies of state-owned banks as his choice target drove this point home."

You can learn more about Attila's backstory on Rubinstein's dedicated website, which includes a 2007 prison interview and an audio clip of Eric Bogosian and Gary Shteyngart performing a scene from the book.

But this is neither a book review nor a handselling seminar. This is simply a moment to consider the ripple effect a book can have on one reader; to reflect on the manner in which words and the world intersect; to realize that the fascinating and entertaining Attila Ambrus in Ballad of the Whiskey Robber is also an ex-convict facing the harsh realities of a country quite unlike the one he knew before he went to prison.

Although I only know Attila through Rubinstein's book, this week I do feel a small link to his world and it is more than a reader's connection. So tonight, for what it's worth, I'm raising a glass to toast the Whiskey Robber and his newfound, complicated freedom.--Robert Gray (column archives available at Fresh Eyes Now)