Although this headline may appear to be the title of a very bad children's book, it actually refers to something we all have lurking on our shelves: the tattered volume that looks as if it should have been tossed out years ago, but still remains nearby. You might even have a little shrine for it between bookends on your desk.

More often, however, your rattiest book is lost in the stacks. It probably has a distinctive, if not always pleasant, scent; a missing dust jacket; boards that are, at best, cracked if not altogether shredded; a threadbare spine; dogeared pages awash in marginalia and highlighted passages; and mysterious stains from decades of proximity to food and beverages.

To qualify as a genuine rattiest book, it must be one you purchased new, kept with you much of your life and would never part with voluntarily. From its shelf perch, your rattiest book has witnessed changing relationships, houses, jobs and friends, not to mention the ongoing arrivals and departures of other, much nicer looking books--cooler books, bestsellers, autographed books or first editions that have slipped through your hands like water while the rattiest book held on.  Let me introduce you to my rattiest book: Walden and Other Writings of Henry David Thoreau, a Modern Library edition I bought new one summer during my college years--probably in 1969 or 1970. At the time, Thoreau mattered more to me than almost anyone, living or dead. I made pilgrimages to Concord, visited Walden Pond and tried to ignore the beachgoers; left a pebble at his grave in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. I carried Walden in my Army surplus knapsack every day then, opened it constantly like a holy book, and over a relatively brief period of time beat it to within an inch of its biblio-life.

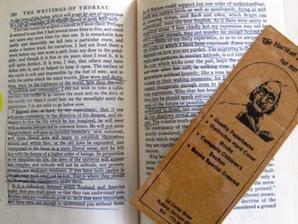

Let me introduce you to my rattiest book: Walden and Other Writings of Henry David Thoreau, a Modern Library edition I bought new one summer during my college years--probably in 1969 or 1970. At the time, Thoreau mattered more to me than almost anyone, living or dead. I made pilgrimages to Concord, visited Walden Pond and tried to ignore the beachgoers; left a pebble at his grave in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. I carried Walden in my Army surplus knapsack every day then, opened it constantly like a holy book, and over a relatively brief period of time beat it to within an inch of its biblio-life.

My rattiest book is still here to tell the tale.

Reading this week about ancient texts from the Vatican and Oxford libraries going online, as well as Larry McMurtry's upcoming "Last Booksale," I couldn't help thinking about "value" because my rattiest book is the most valuable volume in my collection. Although I hadn’t opened it for a long time, yesterday I knew exactly where to find it.

Three years ago, I wrote in a column: "Hidden in an old, broken down Modern Library edition of Henry David Thoreau's Walden was a bookmark from the Hartford Bookshop, Rutland, Vt. Although the bookmark reassured me that the shop was 'est. 1835,' the sad truth is that the Hartford did not make it beyond the 1970s." Now I open my copy of Walden to the same bookmarked page and wonder when I first put that marker there and why. I read a few lines: "I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavours to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours." I liked to underline passages then. Here more of the page is highlighted than not. Guess I grew more selective over the years.

Now I open my copy of Walden to the same bookmarked page and wonder when I first put that marker there and why. I read a few lines: "I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavours to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours." I liked to underline passages then. Here more of the page is highlighted than not. Guess I grew more selective over the years.

I flip pages back to the beginning. Scribbled on the flyleaf, half-title and title pages are what I can only call "poems in the manner of Thoreau," which I wrote in earnest then and scan now with no small measure of embarrassment. But that emotion isn't quite accurate. My rattiest book is a time machine. The poems are markers, too.

I think the patron saint of rattiest books must be the rodent protagonist of Sam Savage's brilliant novel Firmin (Coffee House Press), in which an intellectual rat with a literal as well as literary taste for good books lives in a bookshop where, at one point, he observes the proprietor examining recent purchases from an estate sale:

The rat's suggestion makes sense, especially when I consider the chilling possibility of other people reading my at once awful and oddly precious Thoreauvian poetry. Leave it to my old buddy Firmin to come up with the perfect way to celebrate the true value of our rattiest books.--Robert Gray, contributing editor (column archives available at Fresh Eyes Now)