Leavell covers Moore's early years in depth, perhaps fittingly--in many ways, the poet never outgrew her sheltered youth. Her absent father's religious fanaticism led to his institutionalization for "delusional monomania." When she was 10, her mother fell in love with her pastor's daughter; they shared a surprisingly open relationship for decades. After graduating from Bryn Mawr, Moore never married, moved back in with her mother and had an almost obsessive lifelong attachment to her older brother. Much of their correspondence is still available, and Leavell quotes liberally to fill in the private background that often shadowed Marianne's public life. Eliot, Pound, and William Carlos Williams may have known her as an astute critic and innovative poet, but Moore was still "Fawn" or "Ratty" to her mother and brother.

Without drowning her biography in examples and explication, Leavell traces the evolution of Moore's style with brief illustrations from both published and unpublished work. She comfortably folds critical commentary into her narrative with quotations from the letters of Moore's contemporaries who encouraged and praised her. In the May 1924 issue of Dial, for example, Williams wrote of her work: "Everything is worthless but the best and this is the best."

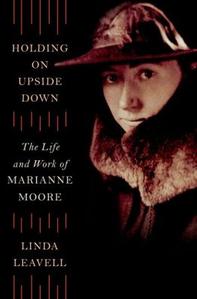

Reed thin and plagued with frequent illness, Moore was a lifelong scholar and poet whose experiments with stanza, rhyme and image heralded the end of 19th-century poetry and the dawn of a freer, more vernacular verse. With what Williams described as "that red hair coiled around her rather small cranium," topped off with her black cape and hat, she became in her later years a popular image of the poet as performer, attending George Plimpton's parties and even tossing the first pitch at Yankee Stadium in 1968. It's no wonder academia turned its back on her. But Holding On Upside Down goes a long way toward restoring Moore's place as a cornerstone of modern American poetry. --Bruce Jacobs

Shelf Talker: Linda Leavell's exhaustive new biography reveals the personal eccentricities of Marianne Moore's life and her place in the vanguard of modern American poetry.