Kate DiCamillo, in her capacity as the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, is demanding that authors and artists flock to their favorite local independent bookstore on Saturday, May 17, during Children's Book Week to read a book aloud. As part of her platform, "Stories Connect Us," she's asked authors and artists in an open letter on the ABA site to read a book that they did not write or illustrate. DiCamillo talked with Shelf Awareness about why she's making these demands.

Kate DiCamillo, in her capacity as the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, is demanding that authors and artists flock to their favorite local independent bookstore on Saturday, May 17, during Children's Book Week to read a book aloud. As part of her platform, "Stories Connect Us," she's asked authors and artists in an open letter on the ABA site to read a book that they did not write or illustrate. DiCamillo talked with Shelf Awareness about why she's making these demands.

We understand that, having stolen Sherman Alexie's idea...

(Ambassador interrupting) Ambassadors don't steal.

Let us rephrase that--we understand that, with Sherman Alexie's permission, you are now recruiting authors and illustrators...

(Ambassador interrupting) I'm demanding it--because I'm an ambassador.

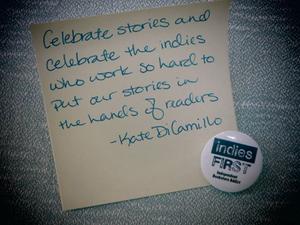

You are demanding that authors and illustrators flock to their local indies and celebrate children's book week--specifically on Saturday, May 17, the inaugural "Indies First Storytime Day"--by reading stories aloud. Is that correct?

Yes, but not a story that they've written. That way, you don't have to worry about criticism. It's not supposed to be about you. It's supposed to be about story.

What book are you planning to read on May 17?

I'm going to read Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus. If anyone criticizes it, I don't have to worry. And I'll report any criticism to Mo Willems.

Is this event designed to enhance your three-month performance appraisal as the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature?

Yes. I have always been the type of person that really, really needs the gold star. You know how the three-month review is, I probably won't get it until the end of April or even late May. By then, I'll have forced everyone to read at the indies.

We've moved from "demand" to "force."

I'm trying to convey how passionately I feel about this.

Jon Scieszka is still waiting for his ambassadorial helicopter. We hope that you are not under similar delusions.

Is he standing on a roof somewhere? I'll go have a word with him. He's waiting for a lot that's never going to happen. He keeps talking about the Fortress of Solitude. I have no idea what he means by that.

In your open letter inviting authors to flock to indies on May 17, you mention The Watsons Go to Birmingham as a prime read-aloud example. Why that book?

I'll start with the truth, which is that the first chapter is so fun to read aloud because it's very funny. That book is one of the first books I read as an adult that was written for children, that was published since I was a kid, and that made me think, "I want to try to do something like this." I took that book home from The Bookman [the now-shuttered wholesaler based in Minneapolis]. Employees were allowed to check books out, and I typed that book up because it meant so much to me. It's a seminal book for me. But it's also a great read-aloud.

Did you welcome those occasions when authors came into The Bookman?

Yes, except I was always intimidated by them. I would hide. Someone would pull me forward and say, "This is Kate; she writes, too," and pat me on the head.

I remember Louise Erdrich looking at me like she saw me, and asking, "How long have you been writing?" I said, "Five years." She said, "Things started happening for me in the sixth year. Keep writing." She took it seriously. And she was right; it was in about the sixth year that things started happening for me.

You also mention a few other picture books as prime read-alouds--I Stink! and The Stinky Cheese Man. Why those?

I Stink! is so much fun to read. I've read that 7,000 times to my young friend Max. There's so much that appeals to a kid. Dirty diapers. Stinky Cheese Man--I don't know why that book has gotten so much attention.

Why is it important to read aloud books that have particular significance to the reader?

Why is it important to read aloud books that have particular significance to the reader?

I'm going to go in there on May 17, and I'm going to read Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus. I'll put the whole of myself in it. That's another book I read to Max to the point that he could recite it along with me. You can make a dialogue with the child that's very natural. I remember going to Lisa Von Drasek's [then children's librarian at Bank Street College] apartment, and her being so excited about that book, and me reaching for it and her slapping my wrist. "Sit down," she said. I sat down, and Lisa stood up and read it to me. I was 40-something, and I thought, "That's what you can do. Look at that." I was on the edge of my seat. I was engaged. I thought it was so funny. And I was a grown-up.

You touched on this a bit already, but why do you feel it's important to tell authors and illustrators not to read from their own books?

It frees us up as writers, because then we get to rejoice in somebody else's work, and that's a lot of what the day's about.

Also, we don't have to worry about whether or not it's any good, which is what I think when I read from my work: "Is it any good?" And then I think, "It's too late to be asking that question."

Incidentally, we could not find Rimson, the Runaway Octopus, a Tale of Tentacles and Glory, the book you cited as a typical bookseller's dilemma. Does such a book really exist?

No, I made it up.

When you Google that title, what comes up is your open letter to authors and artists on the ABA site.

Score one for the Ambassador. It sure would be fun to have a contest for everyone to write a book with that as a title. I think Scieszka could write a good story to go with that.

In which bookstore will you be reading on May 17?

A bookstore in Hudson, Wis., called Chapter 2.

As part of your performance appraisal, we'll call them to make sure you showed up on time.

I've made a career of showing up on time. I used to tell my mother if I don't show up on time, either you've written the time down wrong, or I'm dead. --Jennifer M. Brown