Like many people, I was both "appalled and wryly amused" (see below) by Amazon's recent misunderstanding, misquote and mis-invocation of George Orwell in its battle with Hachette. But the question that came to my mind was one asked last year in the Guardian by Stuart Jeffries: "What would George Orwell have made of the world in 2013?"  I have no idea what Orwell would be thinking, of course. Nor does Jeff Bezos's Amazon Books Team. In a New York Times letter to the editor, literary agent Bill Hamilton, who is also the executor of the Orwell estate, wrote that Amazon "is using George Orwell's name in vain.... This is about as close as one can get to the Ministry of Truth and its doublespeak: turning the facts inside out to get a piece of propaganda across.... I’m both appalled and wryly amused that Amazon’s tactics should come straight out of Orwell’s own nightmare dystopia, 1984. It doesn’t say much for Amazon’s regard for truth, or its powers of literary understanding. Or perhaps Amazon just doesn’t care about the authors it is selling. If that’s the case, why should we listen to a word it says about the value of books?

I have no idea what Orwell would be thinking, of course. Nor does Jeff Bezos's Amazon Books Team. In a New York Times letter to the editor, literary agent Bill Hamilton, who is also the executor of the Orwell estate, wrote that Amazon "is using George Orwell's name in vain.... This is about as close as one can get to the Ministry of Truth and its doublespeak: turning the facts inside out to get a piece of propaganda across.... I’m both appalled and wryly amused that Amazon’s tactics should come straight out of Orwell’s own nightmare dystopia, 1984. It doesn’t say much for Amazon’s regard for truth, or its powers of literary understanding. Or perhaps Amazon just doesn’t care about the authors it is selling. If that’s the case, why should we listen to a word it says about the value of books?

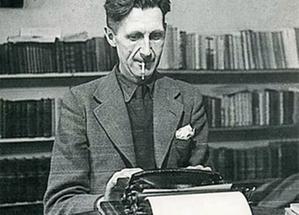

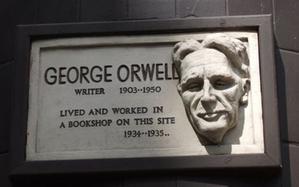

And while it may just be coincidence that Orwell was name-dropped in the middle of a confrontation between an online retail giant and a publisher, it is also appropriate, given that he often wrote about his relationship to books and the book business. In fact, a quick scan of my past columns made me realize I've invoked him more than a few times myself.

In his 1946 essay "Books vs. Cigarettes," Orwell observed that the "idea that the buying, or even the reading, of books is an expensive hobby and beyond the reach of the average person is so widespread that it deserves some detailed examination." After attempting to calculate his book expenditures over 15 years, he estimated that his total reading expenses had been "in the neighborhood of £25 a year," which was £15 less than his tobacco expenses.

"It is difficult to establish any relationship between the price of books and the value one gets out of them," Orwell noted, adding that he had "said enough to show that reading is one of the cheaper recreations.... And if our book consumption remains as low as it has been, at least let us admit that it is because reading is a less exciting pastime than going to the dogs, the pictures or the pub, and not because books, whether bought or borrowed, are too expensive." Because of my own background, I've always been intrigued by Orwell's early work as a bookseller, the fruits of which crop up occasionally in his work. Part of this fascination, I admit, is that his booksellers tend not to be cheerful, "You must read this!" customer-service aficionados. They can be delightfully prickly, as most of us have been in our weaker moments--even while trying not to let it show--on the sales floor. Perhaps I turned to Orwell when I was a bookseller as a release because he often explored the darker side we don't have the freedom to acknowledge publicly. (Succeeding in the bookstore business is hard enough when projecting a positive outlook.) Or maybe I'm just more cynical than you are.

Because of my own background, I've always been intrigued by Orwell's early work as a bookseller, the fruits of which crop up occasionally in his work. Part of this fascination, I admit, is that his booksellers tend not to be cheerful, "You must read this!" customer-service aficionados. They can be delightfully prickly, as most of us have been in our weaker moments--even while trying not to let it show--on the sales floor. Perhaps I turned to Orwell when I was a bookseller as a release because he often explored the darker side we don't have the freedom to acknowledge publicly. (Succeeding in the bookstore business is hard enough when projecting a positive outlook.) Or maybe I'm just more cynical than you are.

In any case, I have an affection for Orwellian booksellers, like the dyspeptic Gordon Comstock in Keep the Aspidistra Flying, who considers his fate among the stacks at Mr. McKechnie's bookshop: "This was the lonely after-dinner hour, when few or no customers were to be expected. He was alone with seven thousand books. The small dark room, smelling of dust and decayed paper, that gave on the office, was filled to the brim with books, mostly aged and unsaleable. On the top shelves near the ceiling the quarto volumes of extinct encyclopedias slumbered on their sides in piles like the tiered coffins in common graves."

In his essay "Bookshop Memories," Orwell recalled: "When I worked in a second-hand bookshop--so easily pictured, if you don't work in one, as a kind of paradise where charming old gentlemen browse eternally among calf-bound folios--the thing that chiefly struck me was the rarity of really bookish people. Our shop had an exceptionally interesting stock, yet I doubt whether ten per cent of our customers knew a good book from a bad one.... Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop."

Also: "Would I like to be a bookseller de métier? On the whole--in spite of my employer's kindness to me, and some happy days I spent in the shop--no.... Given a good pitch and the right amount of capital, any educated person ought to be able to make a small secure living out of a bookshop.... Also it is a humane trade which is not capable of being vulgarized beyond a certain point. The combines can never squeeze the small independent bookseller out of existence as they have squeezed the grocer and the milkman."

Ah, but they do try, don't they? What would Mr. Orwell have made of the book world in 2014? --Robert Gray, contributing editor (column archives available at Fresh Eyes Now)