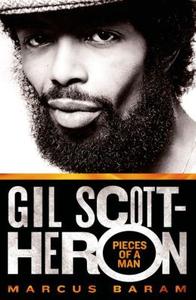

Baram, managing editor of International Business Times who boasts numerous bylines from the Huffington Post, the New York Times, Vibe and New York magazine, knew Scott-Heron and had access to the recollections of the musician's family, friends and bandmates as well as those of the man himself. From this rich material, Scott-Heron's life becomes clear, starting with his tough childhood under the care of his grandmother Lillie (who took him in after his Jamaican soccer-playing father left the family and his mother set off on her own career in South Carolina and New York City).

With his intellect (evident despite his poor grades) and easy way with people, the tall, skinny Scott-Heron worked the diversity angle to breach the admission walls at a tony New York prep school, then enrolled in Langston Hughes's alma mater, Lincoln University, and finally earned an MFA at Johns Hopkins, despite dropping out of Lincoln before graduation in order to write novels and songs. Along the way, he participated in campus protests against the Vietnam War and racial injustice and joined Washington's politically active Lost Poets writer colony.

It was his music that most engaged him and touched the widest audience. His enduring songs "The Bottle" and "Johannesburg" cracked the Billboard charts and led to financially rewarding recording contracts. His poem "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" found its lyrics and title co-opted by nearly everyone with a revolutionary agenda, including a Mexican rock band, recent Greek student protesters and even Nike's advertising department. In addition to his documentary of Scott-Heron's concert, Mugge also featured him in his underground classic reggae film Cool Runnings.

For a while, Scott-Heron was riding a rising tide, upgrading his mother's Bronx apartment and finding easy access to the coke and drugs that fueled the music industry. It was the latter that did him in. Missed gigs, drug busts, jail time, rehab... it's a well-trod path. Baram tells it all, including the support Scott-Heron received from musical movers like Run-DMC, Grandmaster Flash and Stevie Wonder. In the words of a 1976 Playboy profile, he could make "proud Afro-scats bugaloo the midnight streets." When Scott-Heron was on, he was indeed the "ghetto griot." --Bruce Jacobs, founding partner Watermark Books & Cafe, Wichita, Kan.

Shelf Talker: With access to Scott-Heron and his family and friends, journalist Marcus Baram has crafted the first full-length biography of this seminal figure in black music and late 20th-century politics.