Authors write books and readers read them. It's a deceptively simple contract. Booksellers are professional readers who get to discover works before they're reviewed or released, thanks to the ARC avalanches that bury, in the best possible way (mostly), bookstores everywhere. Agents, editors and publishers may justifiably profess to being the readers who truly discover new works, but booksellers still plant a flag of their own with staff picks.

Given the intimate connection on the printed page between authors and their readers--in the book trade and beyond--certain questions inevitably arise. What is the true nature of this relationship? Where is the borderline? What do authors "owe" their readers beyond the work itself? And when a reader tumbles down the rabbit hole and fully enters a fictional world, does the novel's alchemy change? Whose book is it anyway?

"To my mind, to understand a character is to understand his inner voice," she said. I immediately thought about my favorite authors, narrators and characters; as well as all of those other readers who breathe life into letters on a page with their own disparate inner voices. Reading is a creative, collaborative act, and hearing voices plays a key role. Polyphony? Cacophony? It depends.

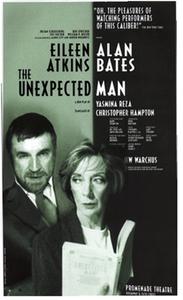

This sparked a memory from 15 years ago, when I saw the brilliant off-Broadway production of Reza's The Unexpected Man, starring Eileen Atkins and Alan Bates. The play is about two strangers, in their 60s, sitting opposite each other on a train from Paris to Frankfurt. For all but the final 10 minutes, they speak only in interior monologues (to me, audience members might reasonably think), each caught up in personal obsessions while occasionally, and surreptitiously, observing the other.

Paul Parsky is a dyspeptic Author (his opening lines: "Bitter. It's all so bitter."), while Martha, we soon discover, is his Reader. She recognizes him immediately, but remains discreet. In her handbag she carries a copy of his novel, The Unexpected Man, and she wonders whether she should speak to him or just "fetch out" the book and read it.  For his part, the Author simply passes judgment:

For his part, the Author simply passes judgment:

Martha again considers unmasking herself as his Reader:

She also contemplates an all-to-familiar social dilemma:

Then the Reader finally stakes her claim to his books:

At last, like Chekhov's loaded gun, the novel is brandished and the Author struck by its appearance:

They have a brief conversation. The Author attempts to conceal his identity, but the Reader counters that move by citing examples from his work, concluding:

I won't reveal how the play ends, but it's safe to say the relationship between Author and Reader remains a complex one even after the applause has died down. Whose book is it? Why spoil the mystery. --Robert Gray, contributing editor (column archives available at Fresh Eyes Now)