|

|

| photo: Alexa Seidl MacKinnon | |

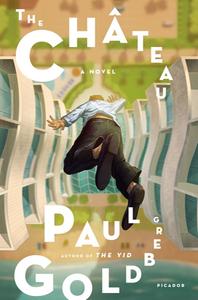

Paul Goldberg's debut novel, The Yid, was published in 2016 to widespread acclaim and named a finalist for both the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and the National Jewish Book Award's Goldberg Prize for Debut Fiction. As a reporter, Goldberg has written two books about the Soviet human rights movement and has co-authored (with Otis Brawley) the book How We Do Harm, an expose of the U.S. healthcare system. He is the editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter, a publication focused on the business and politics of cancer. His new novel, The Chateau, will be published by Picador on February 13, 2018. He lives in Washington, D.C.

On your nightstand now:

The Bughouse: The Poetry, Politics, and Madness of Ezra Pound by Daniel Swift. It's a fascinating account of the life and deranged thinking of Ezra Pound, focused on the 12 years he spent at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington. Whoever said that a Nazi sympathizer and a virulent anti-Semite can't also be an important poet? I am also trying to sit through Pound's poetry, so there is a copy of The Cantos next to The Bughouse. A friend promised to arrange a visit to St. Elizabeths. I think this may feed it into my next novel.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Withot a doubt, Jaroslav Hašek's The Good Soldier Švejk. My mother read that book to me in 1968. I was nine years old and living in Moscow.

When "our" tanks put an end to Prague Spring, we were deep in the book. It felt as though those tanks were passing through our Moscow apartment. Švejk embodies the Czech national character much like Onegin embodies Russia, and Huck Finn embodies America.

Gigantic as this is, Švejk also owns the utter dullness and dimwittedness of war. There are echoes of Švejk in Catch-22, and, I would argue, M*A*S*H.

Your top five authors:

Aleksandr Pushkin

Nikolai Gogol

Jaroslav Hašek

Mark Twain

Mikhail Bulgakov

Book you've faked reading:

The Bible.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita. It's wonderful homage to Gogol, Cervantes, Goethe and Dante. Yet it's set in Moscow at the time of the onset of Stalin's rule. I don't think anyone--anyone--has ever captured the soul of Moscow the way Bulgakov does in this book.

Book you've bought for the cover:

There is a lot of architecture and design in my books and, I suppose, in my life. In architecture as in literature, I am fascinated by modernism, the stripping away of unnecessary detail, bringing things down to their essence. I buy a lot of architecture and design books. My all-time favorite is Case Study Houses by Elizabeth Smith and Peter Gossel.  Book you hid from your parents:

Book you hid from your parents:

The nicest thing about my parents was that I didn't have to hide books from them. All books were encouraged.

Book that changed your life:

Aleksandr Fadeyev's novella titled in Russian Razgrom, translated into English as The Rout.

It's a story of a band of Red partisans fighting--and largely fleeing--in the Ural woods. The principal character's name is Levinson. He is the brave and wise commander of the band, and though I realized that Razgrom is not great literature, I liked the character enough to incorporate him and his back story into my first novel, The Yid. My Levinsonesque character, whose name is Levinson, gets a second act as an actor at the Moscow State Jewish Theater.

Favorite line from a book:

It's a poem by Osip Mandelstam. He really lets Stalin have it. Alas, Mandelstam was sent off to the camps and died for having written it.

We live without feeling the country beneath us,

our speech at ten paces inaudible,

and where there are enough for half a conversation

the name of the Kremlin mountaineer is dropped.

His thick fingers are fatty like worms,

but his words are as true as pound weights.

His cockroach whiskers laugh,

and the tops of his boots shine.

I read it in Russian. This translation is by David McDuff in Osip Mandelstam: Selected Poems published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973.

Five books you'll never part with:

1. I still own that copy of Švejk that my mother read to me in 1968.

2. I have two autographed copies of Shmuel Halkin's collected poems. I have the Russian translation. Halkin, a poet and a playwright, translated King Lear into Yiddish.

3. Moskva-Petushki by Venedikt Yerofeyev. This book started in samizdat, which means it was circulated in a typewritten version. I have a version published by Ardis Publishing, which at the time was in Ann Arbor, Mich. It's a brief, surreal story of a drunk taking a train ride from Moscow to a nearby town. The names of railroad stations break the book up into chapters. The thing is brilliant but, alas, untranslatable. Attempts at translation are titled Moscow to the End of the Line, Moscow Stations and Moscow Circles.

4. A poetry book autographed by Aleksandr Galich. I grew up listening to his tape-recorded songs. These were brilliant, complex compositions, sometimes satirical, sometimes meditative. Sometime around 1973, I came to his concert in Washington and he signed a book for me. At the time, I wouldn't have cared about seeing Mick Jagger as much as I cared about Galich. This is still the case.

5. Dal's dictionary of the Russian language. It's an amazing piece of work, a kind of Russian Webster's. I used it several times in writing The Chateau. Alas, in his capacity as a czarist official, Dal perpetuated the canard about Jews using Christian blood in religious rituals. That canard was a part of the inspiration for The Yid.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Exodus by Leon Uris. I read the Russian translation in Moscow. It was circulated through samizdat, and my parents and I had it for one night. We shared loose-leaf pages. Technically, we could have been prosecuted for this, charged with anti-Soviet propaganda. This had to be around 1971. When I re-read the book in the U.S., without a threat of prosecution, I was underwhelmed.